Since the end of World War II, a commitment to open trade — paired with ironclad security agreements with Japan and NATO — had been the cornerstone of American foreign policy. Last Thursday, those decades of political investments in increasing global integration halted with a simple word: “no.”That was the answer of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to reporters’ questions on whether the controversial trade deal called the Trans-Pacific Partnership would be brought up for a vote during the lame-duck session of Congress preceding Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th president of the United States. The soon-to-be Senate Minority Leader, Democrat Chuck Schumer of New York, confirmed that the deal was dead in conversations with labor leaders.“It’s clear we’re not going to get deeper globalization right now,” said Chad P. Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “The question is whether we stay where we are or whether there’s a major reversal.”Obviously, the reason why is the strangely coiffed political whirlwind that rocked the U.S. last week. The Electoral College victory that made Republican Donald J. Trump president-elect was viewed as a broad-based repudiation of decades of American political conventions, including some long-standing issues of bipartisan consensus, with trade foremost among them.At least that’s how it’s being received overseas. On Monday, China’s state-run Global Times fired a shot across the bow, saying a trade war would be “naive” and have grave consequences for iPhones, Boeing aircraft, and U.S. car manufacturers. (The statement sent Apple shares down 3 percent.) “If Trump wrecks Sino-U.S. trade, a number of U.S. industries will be impaired,” the paper said in an editorial.The era of globalization was born in the aftermath of World War II, when the United States made the decision that open trade and security guarantees with Japan and NATO would be the only way to avoid another war and counterbalance Soviet expansion. It gathered force 27 years ago, amid the jubilant ping of hammers bringing down the Berlin Wall. The fall of Communism there brought roughly half the globe into the system established by the victorious WWII allies.In 2001, China’s entry to the World Trade Organization brought the world’s most populous country into the system — a climax of the globalization push that has so far pulled some 800 million Chinese out of poverty but had serious and long-lasting consequences for the working classes in the developed world.Recent research, notably from MIT’s David Autor and the University of California, San Diego’s Gordon Hanson, has outlined the stark consequences of China’s entry into the world trading system for working-class Americans, which accelerated the pace of manufacturing-job losses in many communities with industries exposed to Chinese manufacturing.To be clear, this is a story of long-term decline. As recently as 1970, factories accounted for 1 in 4 U.S. jobs. Today, it’s less than 1 in 10. Factory work was heavily male and well-paid, providing a great source of jobs for men who didn’t go to college.

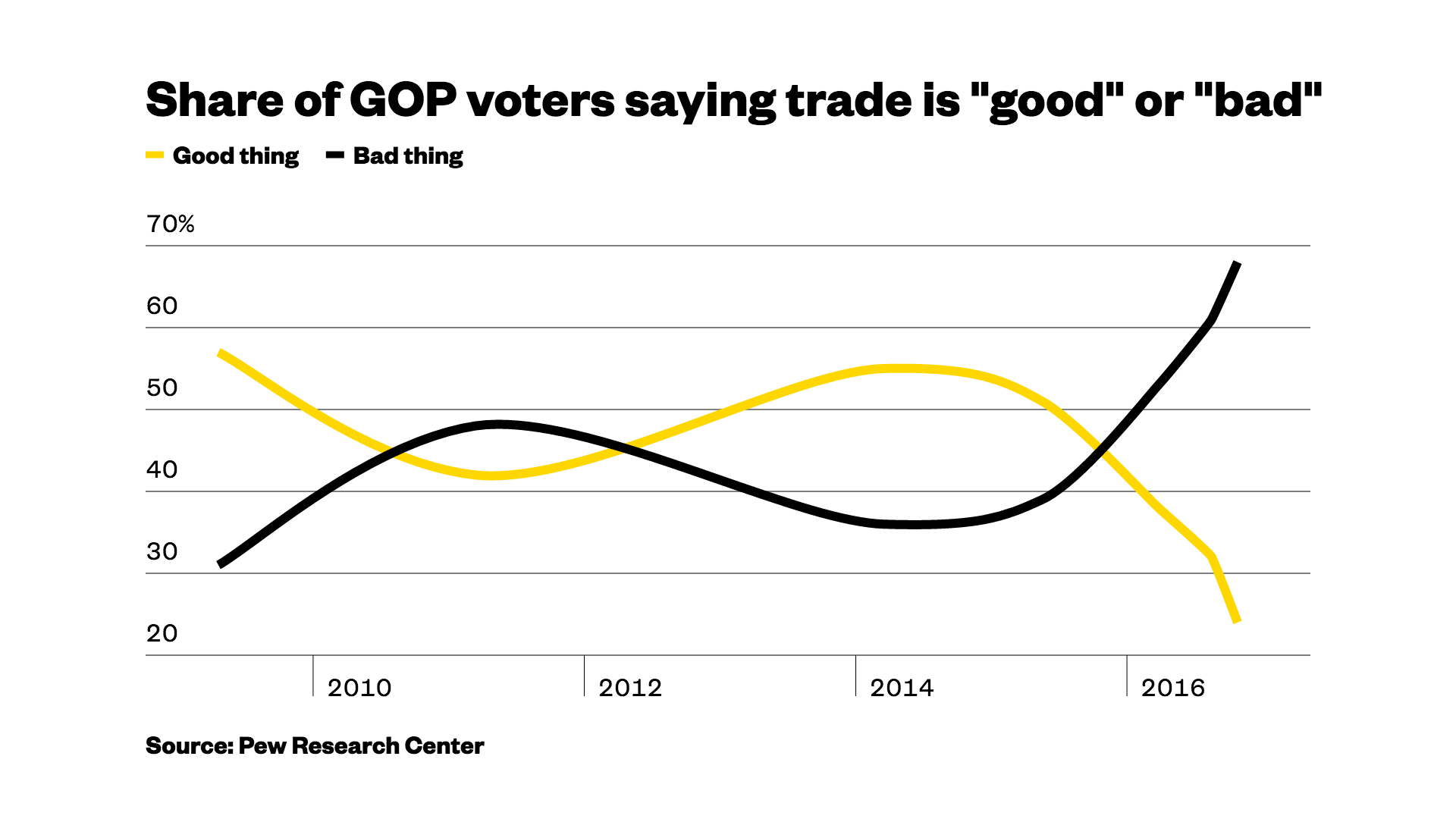

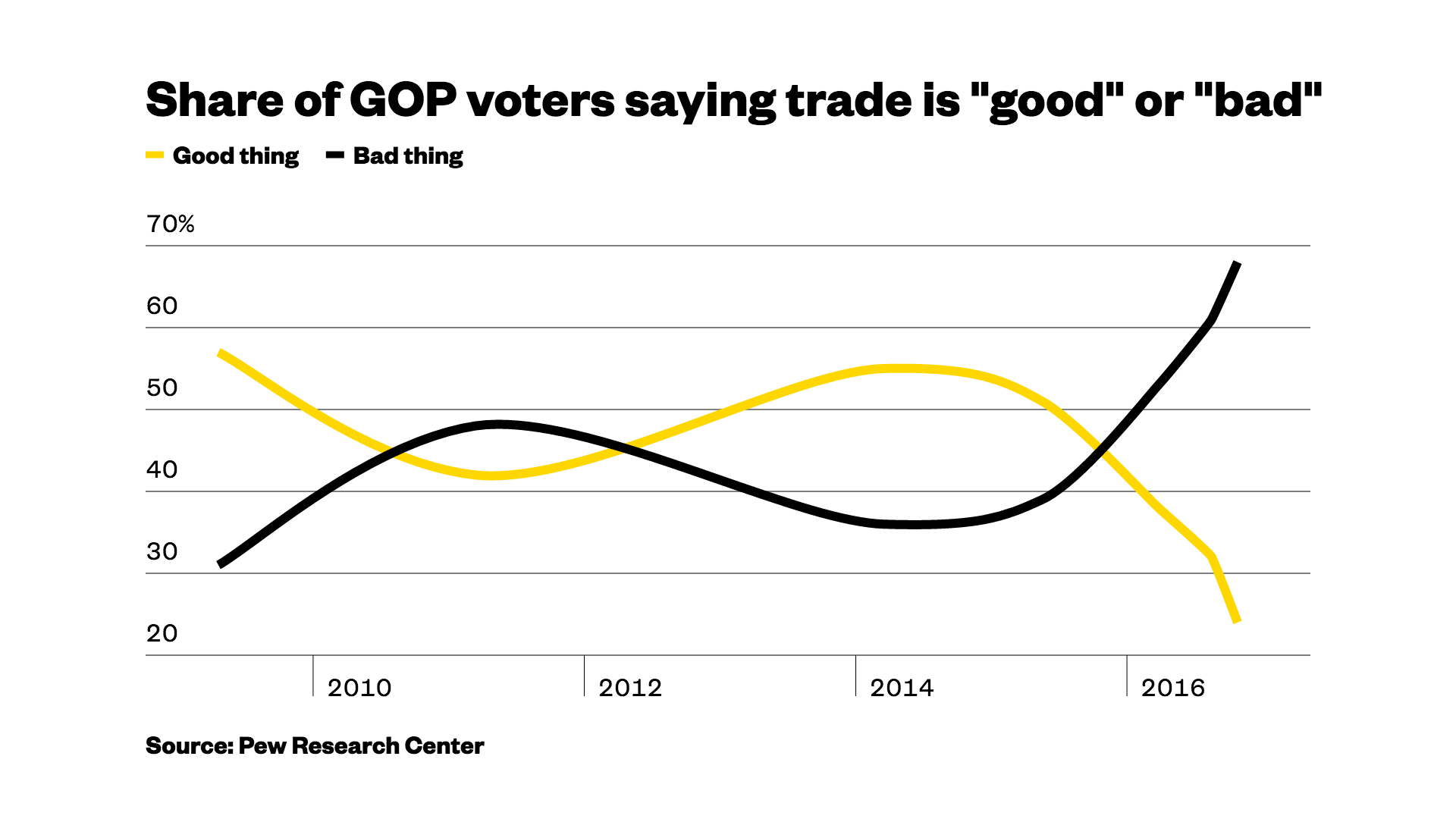

But the share of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. began to shrink in the 1970s, a trend that only picked up steam in recent years as China became, essentially, the workshop of the world. Over the last 20 years, some 5 million manufacturing jobs disappeared as the U.S. economy shifted toward service jobs and felt the impact of foreign trade and technological change.Driven by concerns about such job loss, U.S. support for trade has declined in recent years, as the financial crisis undercut confidence in pronouncements from economic policymakers. Rising inequality made any benefits of trade — such as the low cost of consumer goods made in Asia — seemingly miniscule compared to the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs.Most importantly, support for trade collapsed among Republicans, the traditional champions of free trade and laissez-faire economics. Donald Trump made criticism of trade deals — especially the North American Free Trade Agreement, enacted under President Bill Clinton — a cornerstone of the populist appeal that led to his election. Likewise, opposition to TPP fueled Bernie Sanders’ insurgent campaign for the Democratic nomination. The eventual Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, also opposed TPP, despite having said while she was secretary of state in 2012 that it “sets the gold standard” for trade deals.

It gathered force 27 years ago, amid the jubilant ping of hammers bringing down the Berlin Wall. The fall of Communism there brought roughly half the globe into the system established by the victorious WWII allies.In 2001, China’s entry to the World Trade Organization brought the world’s most populous country into the system — a climax of the globalization push that has so far pulled some 800 million Chinese out of poverty but had serious and long-lasting consequences for the working classes in the developed world.Recent research, notably from MIT’s David Autor and the University of California, San Diego’s Gordon Hanson, has outlined the stark consequences of China’s entry into the world trading system for working-class Americans, which accelerated the pace of manufacturing-job losses in many communities with industries exposed to Chinese manufacturing.To be clear, this is a story of long-term decline. As recently as 1970, factories accounted for 1 in 4 U.S. jobs. Today, it’s less than 1 in 10. Factory work was heavily male and well-paid, providing a great source of jobs for men who didn’t go to college.

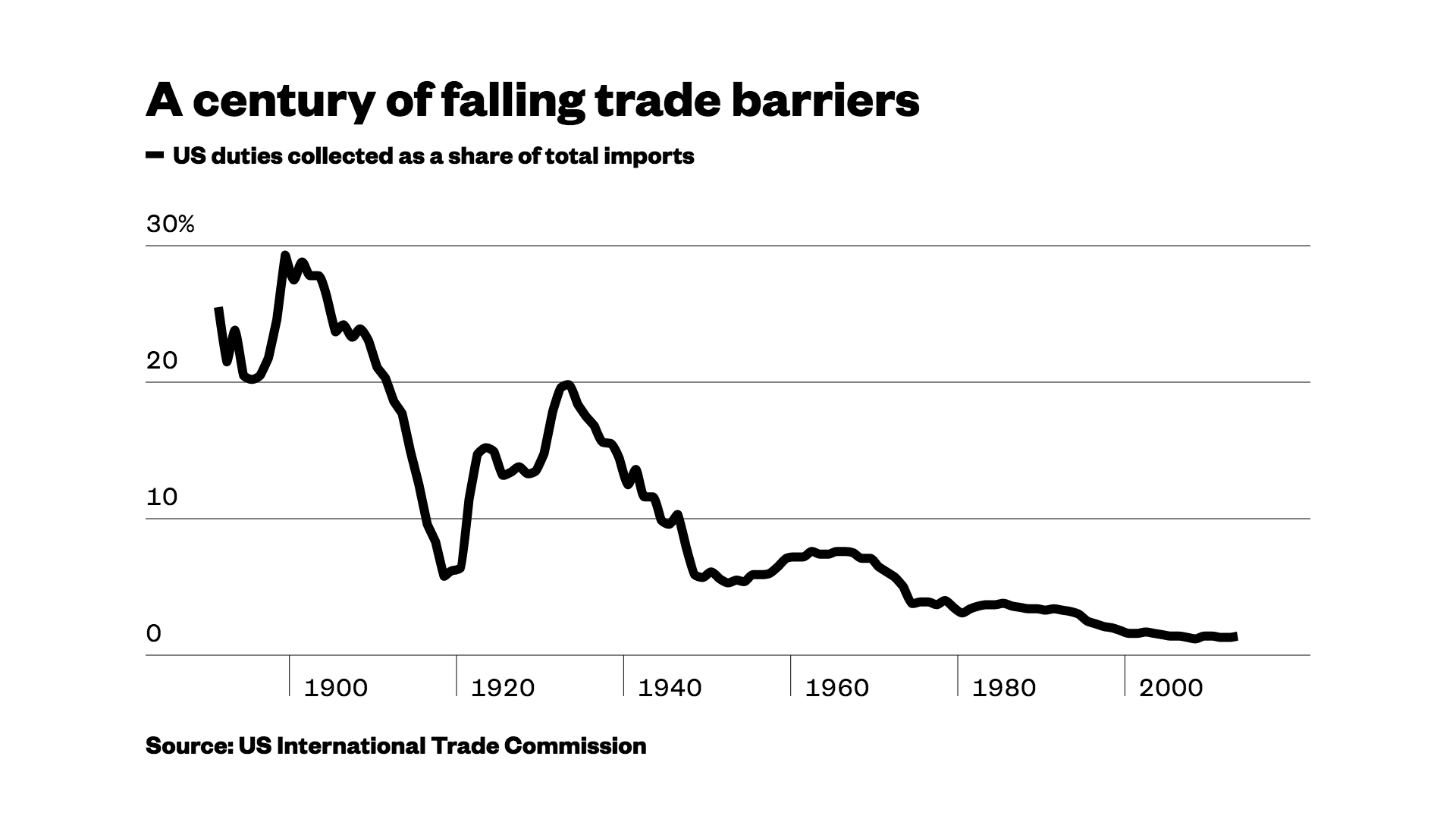

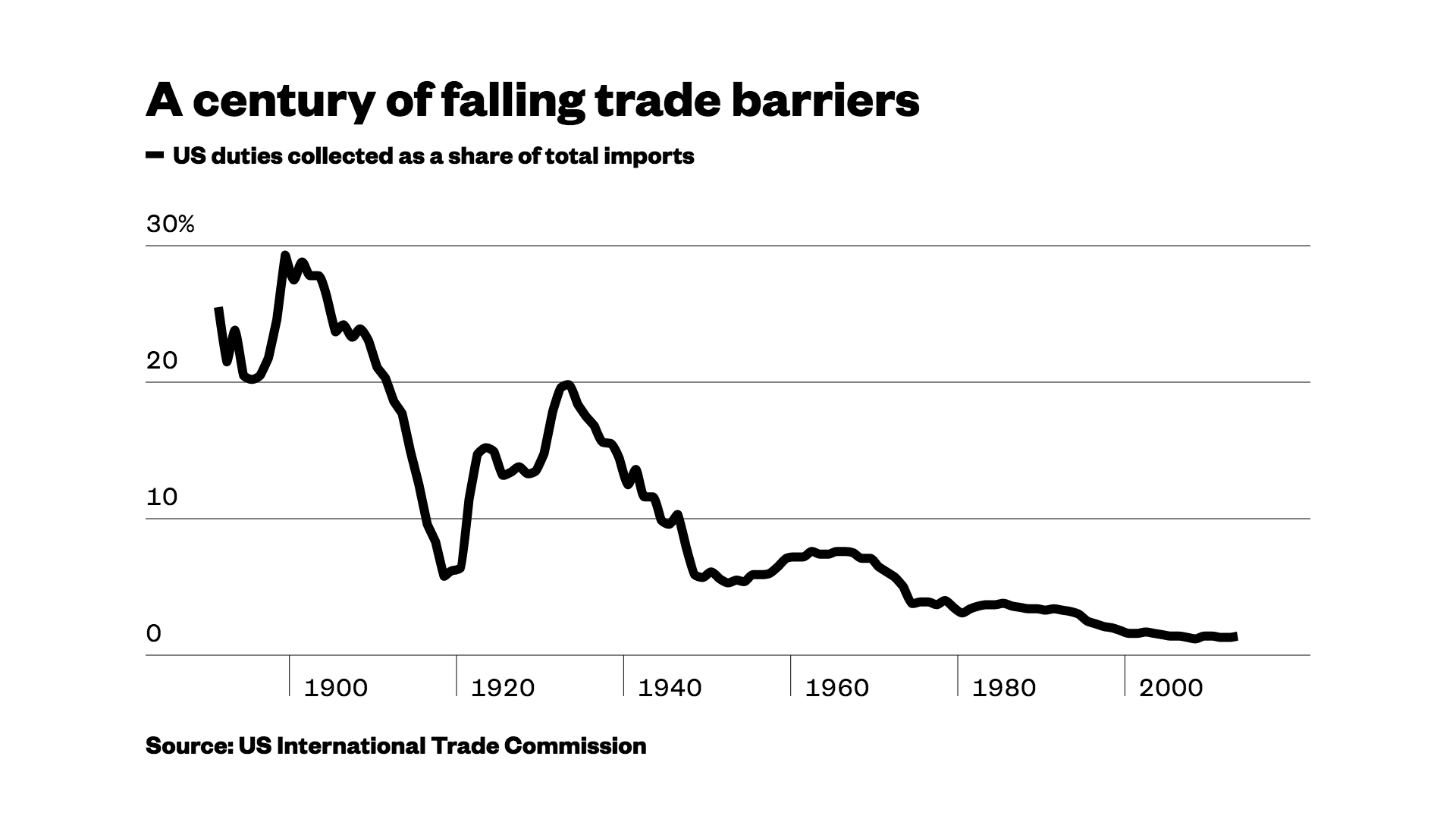

But the share of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. began to shrink in the 1970s, a trend that only picked up steam in recent years as China became, essentially, the workshop of the world. Over the last 20 years, some 5 million manufacturing jobs disappeared as the U.S. economy shifted toward service jobs and felt the impact of foreign trade and technological change.Driven by concerns about such job loss, U.S. support for trade has declined in recent years, as the financial crisis undercut confidence in pronouncements from economic policymakers. Rising inequality made any benefits of trade — such as the low cost of consumer goods made in Asia — seemingly miniscule compared to the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs.Most importantly, support for trade collapsed among Republicans, the traditional champions of free trade and laissez-faire economics. Donald Trump made criticism of trade deals — especially the North American Free Trade Agreement, enacted under President Bill Clinton — a cornerstone of the populist appeal that led to his election. Likewise, opposition to TPP fueled Bernie Sanders’ insurgent campaign for the Democratic nomination. The eventual Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, also opposed TPP, despite having said while she was secretary of state in 2012 that it “sets the gold standard” for trade deals. The controversial trade pact linked 12 nations through a series of agreements that would have eliminated 18,000 tariffs on important U.S. exports like food products and chemicals, according to government officials, who claimed it would be good for overall economic growth. It also excluded China, effectively pulling a range of emerging Asian economies like Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia more closely into the geopolitical orbit of the U.S.But there’s a growing consensus that the demise of TPP represents more than a trade deal run aground. They point to a growing global backlash against the post–World War II economic consensus that the benefits of increasing the cross-border flow of products, capital, and, to a certain extent, people, outweigh the costs.While Trump has threatened to use tariffs as a weapon, particularly against China, there’s little indication that barriers to trade will rise immediately upon Trump’s arrival in the White House. So for the moment, trade barriers remain quite low, advocates say, where they might well stay.“That wouldn’t be the end of the world,” said Bown of the Peterson Institute. “It would be very, very different to reverse all of that and go back to what we had in the 1930s.”

The controversial trade pact linked 12 nations through a series of agreements that would have eliminated 18,000 tariffs on important U.S. exports like food products and chemicals, according to government officials, who claimed it would be good for overall economic growth. It also excluded China, effectively pulling a range of emerging Asian economies like Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia more closely into the geopolitical orbit of the U.S.But there’s a growing consensus that the demise of TPP represents more than a trade deal run aground. They point to a growing global backlash against the post–World War II economic consensus that the benefits of increasing the cross-border flow of products, capital, and, to a certain extent, people, outweigh the costs.While Trump has threatened to use tariffs as a weapon, particularly against China, there’s little indication that barriers to trade will rise immediately upon Trump’s arrival in the White House. So for the moment, trade barriers remain quite low, advocates say, where they might well stay.“That wouldn’t be the end of the world,” said Bown of the Peterson Institute. “It would be very, very different to reverse all of that and go back to what we had in the 1930s.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement