In this week’s reporting from the chaos of the coup in Thailand, from the midst of martial law, and a clambering to describe events in a nation that is all too often fetishized as some paradisiacal “Orient,” something familiar emerged: The selfie.

A number of news outlets, including the AP, reported on the phenomenon of “Bangkok residents going about their morning routine [who] didn’t hesitate to stop and snap a few photos on their smartphones.” And a host of coup-selfies have emerged online since Tuesday’s announcement of martial law.

Videos by VICE

As Drake — that bearer of millennial cultural capital — put it: “Now you’re talking my language.” Through the fog of a complicated political circumstance, the selfie presented itself as both legible and strange. There’s a certain comforting universality to it: The same approach and use of technologies applied to taking pictures of Thai military officers enacting a curfew is applied to Instagraming a lazy morning with one’s cat.

There’s a few available readings here. One sees the coup treated as Thai normality, as unmiraculous and predictable as birthday party — hold up your smartphone, take a picture. An other view (not mutually exclusive) recognizes the broad application of the selfie as narrative form in our epoch. Selfies in the Thai coup are a reflection of the ubiquity of advanced techo-capital’s modes of narrativizing events, and including ourselves in them.

‘The global application of these technologies collapses complex narratives into the pre-determined formats provided by social media and phone technology platforms.’

Writers, including Molly Crabapple and Huw Lemey, have explored, respectively, the use of social media by fundamentalist tourists in Syria and Israeli Defense Force soldiers. As Lemey put it, when war is mediated through platforms like Instagram and Twitter, “We see a newer aesthetic; a hybrid of networked technology, social media theory and a visual regime based around firmly entrenched, conservative branding techniques.”

Lemey highlights that there is something conservative and conformist about the ways social media-based images and texts package even the most extreme circumstances of war and occupation. Yes, there is something expansive and unforeclosed about how any person, anywhere in the world, so long as they have a smartphone, can capture their own narratives of a given event — from coups, to Jihad, to occupation.

But there is a flattening of narrative, too, through this prism of techno-capital. There are only so many characters allowed in each tweet, only so many Instagram filters. The global application of these technologies collapses complex narratives into the pre-determined formats provided by social media and phone technology platforms.

In some ways, ’twas ever thus: what gets to be history is constrained by the current forms of recounting and narrativizing. And contemporary technologies carry the interesting consequences, through the art and ubiquity of the selfie, as one very current example, to enable many more people than ever before to insert themselves into the recorded annals of world history. This carries the risk, too, however, of rendering a coup an event as ordinary as a kitten.

Follow Natasha Lennard on Twitter: @natashalennard

More

From VICE

-

KATERYNA KON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/GETTY IMAGES -

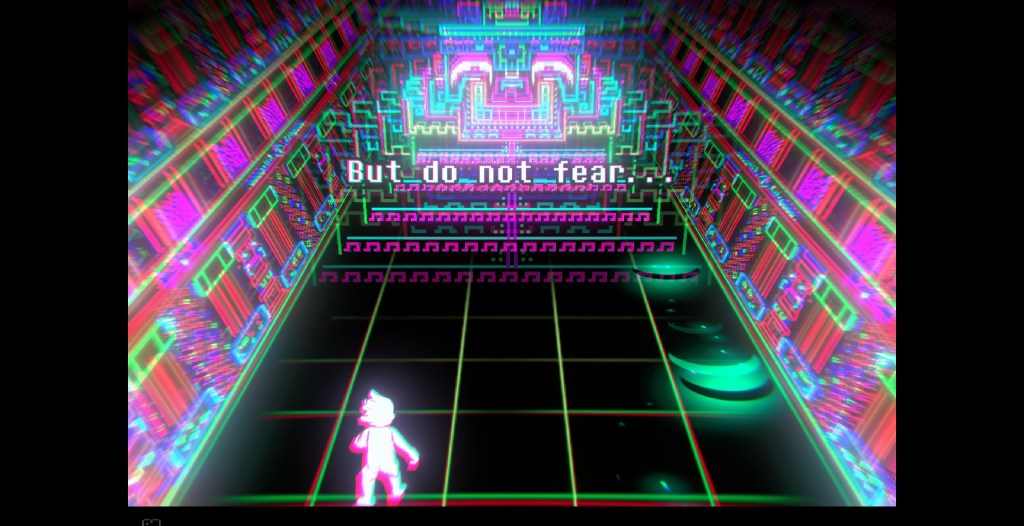

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Carol Yepes/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki