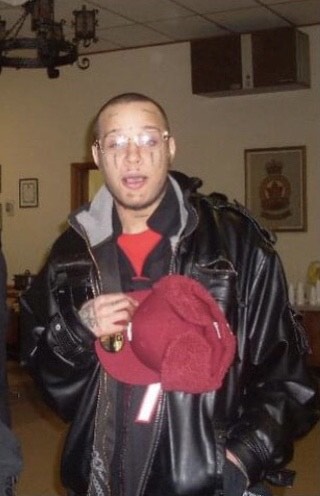

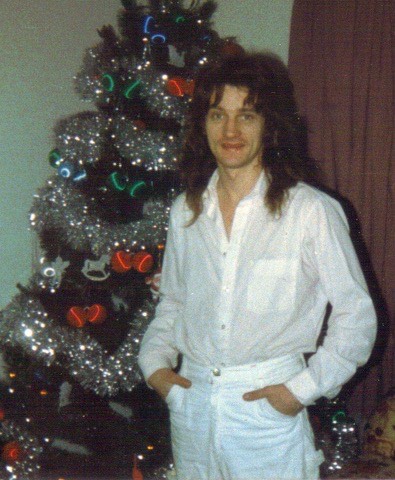

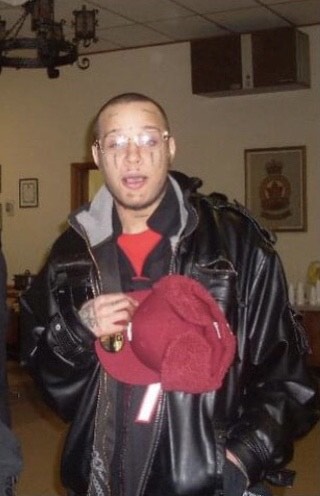

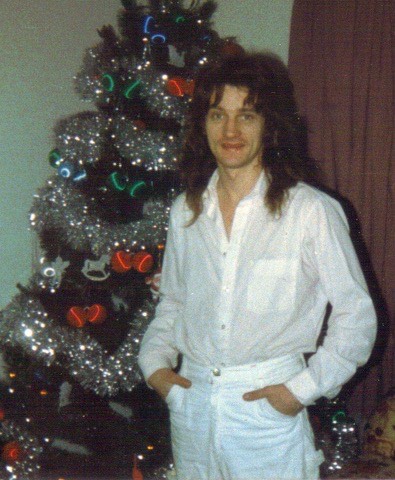

Seth Maclean's sister and brother Taliyah Francis (left) and Lamar Maclean (right) at Seth' gravestone. Photo supplied

Seth Maclean, who died on July 12 from a fatal drug overdose and was buried without his family knowing in a graveyard the following month, was assigned the number 536. Like Maclean, hundreds of people in Ontario—many of whom are homeless and struggle with addiction or mental health issues—die without having their next of kin notified every year.In 2019, there were 517 such cases, and in 2020, where overdose deaths are spiking amid the pandemic, there have already been 630 as of November 9.Under the province’s Anatomy Act, bodies that cannot be properly connected to next of kin are referred to as “unclaimed,” and are to be given a simple burial at a site chosen by the municipality where the person died. Far from a dignified funeral, unclaimed bodies are put into featureless wooden boxes, sometimes without clothes, and are buried 6 feet deep in plots of land across the province.Essentially unmarked, the graves are identifiable only by a small numbered plate to indicate when they entered the graveyard in comparison to other unclaimed bodies.In the weeks after Maclean’s death, his family remained unaware of what had happened, at first chalking up his absence to his usual erratic behaviour and propensity for ghosting.“My sister had been looking for weeks, and I told her to wait and see a little longer,” said Tyson Maclean, Seth’s uncle, noting how Seth’s struggle with drug addiction and homelessness meant he was not always easy to get a hold of.“It wasn’t unusual. The addiction, the way we understand it works, makes people go missing for periods of time.” It wasn’t until September 10, on what would have been Seth’s 32nd birthday, when Tyson and the Maclean family found out the truth. While filing a missing person’s report with Toronto police’s 51 Division, an officer let Seth’s mother know that he had already been dead for two months.Under the procedure for “compassionate messages”—the name they give to informing the next of kin—Toronto police lay out a short list of tasks for officers to find family and friends of the deceased.If next of kin cannot be contacted after asking friends, neighbours, social agencies, and members of the community, the guidelines request that the police or coroner’s office contact the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee.But that appears to not have happened in this case. Tyson, who was Seth’s emergency contact, never received a call from police, and said he thinks that whoever conducted the investigation “decided it wasn’t worth the effort.” Seth’s mother, grandmother, and aunt were his trustees. Tyson said that Seth, who had severe schizophrenia and had been arrested over 100 times for a range of violent episodes and petty crimes, was known to police and had a negative reputation because of past incidents, which he believes made authorities biased against him.“I believe because of his illness, who he was, the amount of charges he had racked up, I believe he was thrown to the wayside like a piece of garbage, like his life didn’t matter,” Tyson said.Toronto police spokesperson Meaghan Gray told VICE News in an email that the police cannot discuss individual investigations due to privacy, but explained that agencies contacted by police are not compelled to hand information over. This happens frequently and often makes locating next of kin for some people a difficult task, she said.In a candid interview, the Chief Coroner of Ontario, Dr. Dirk Huyer, admitted that “there may have been steps that were not followed” when contacting the Maclean family.Huyer described the current system as needing room for improvement, citing a number of reasons that can complicate contacting next of kin, such as estrangement from family and lack of up-to-date contact information. Although he could not comment on Maclean’s’s specific case or answer why Tyson was not contacted as the trustee, Huyer said both the coroner’s office and police must strive for a higher standard of treatment for at-risk individuals.“My personal and professional opinion is that it should be the opposite,” Huyer said about potential bias against those with addiction and mental health issues.“These are people who sometimes don’t have next of kin, and we should make all efforts to give them a dignified burial. When they’re unclaimed, we’re like their family. We’re acting as their family,” he said.The Maclean family is not alone in feeling at a loss for answers. In June 2014, 51-year-old Gary Cormier was found dead at the bottom of a Toronto apartment building. Police concluded that Cormier, high on crystal meth, jumped off a balcony a number of floors up after cutting his way through mesh bird netting.

It wasn’t until September 10, on what would have been Seth’s 32nd birthday, when Tyson and the Maclean family found out the truth. While filing a missing person’s report with Toronto police’s 51 Division, an officer let Seth’s mother know that he had already been dead for two months.Under the procedure for “compassionate messages”—the name they give to informing the next of kin—Toronto police lay out a short list of tasks for officers to find family and friends of the deceased.If next of kin cannot be contacted after asking friends, neighbours, social agencies, and members of the community, the guidelines request that the police or coroner’s office contact the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee.But that appears to not have happened in this case. Tyson, who was Seth’s emergency contact, never received a call from police, and said he thinks that whoever conducted the investigation “decided it wasn’t worth the effort.” Seth’s mother, grandmother, and aunt were his trustees. Tyson said that Seth, who had severe schizophrenia and had been arrested over 100 times for a range of violent episodes and petty crimes, was known to police and had a negative reputation because of past incidents, which he believes made authorities biased against him.“I believe because of his illness, who he was, the amount of charges he had racked up, I believe he was thrown to the wayside like a piece of garbage, like his life didn’t matter,” Tyson said.Toronto police spokesperson Meaghan Gray told VICE News in an email that the police cannot discuss individual investigations due to privacy, but explained that agencies contacted by police are not compelled to hand information over. This happens frequently and often makes locating next of kin for some people a difficult task, she said.In a candid interview, the Chief Coroner of Ontario, Dr. Dirk Huyer, admitted that “there may have been steps that were not followed” when contacting the Maclean family.Huyer described the current system as needing room for improvement, citing a number of reasons that can complicate contacting next of kin, such as estrangement from family and lack of up-to-date contact information. Although he could not comment on Maclean’s’s specific case or answer why Tyson was not contacted as the trustee, Huyer said both the coroner’s office and police must strive for a higher standard of treatment for at-risk individuals.“My personal and professional opinion is that it should be the opposite,” Huyer said about potential bias against those with addiction and mental health issues.“These are people who sometimes don’t have next of kin, and we should make all efforts to give them a dignified burial. When they’re unclaimed, we’re like their family. We’re acting as their family,” he said.The Maclean family is not alone in feeling at a loss for answers. In June 2014, 51-year-old Gary Cormier was found dead at the bottom of a Toronto apartment building. Police concluded that Cormier, high on crystal meth, jumped off a balcony a number of floors up after cutting his way through mesh bird netting. Similar to the Maclean case, Cormier’s sister, Wanda Rose, learned about her brother’s death on December 9, 2014, just days after his 52nd birthday and about six months after his actual death. Since June, Rose had become increasingly worried about Cormier, and eventually decided to call 51 Division, when she learned of her brother’s fate.Since that day, Rose said she has never heard again from Toronto police. They offered her little explanation as to why the family wasn’t contacted, she said, nor did they disclose how they decided that his death was a suicide. In her attempts to investigate, Rose was not able to get a hold of the woman said to live in the unit where Gary jumped from, and believes—not unlike Tyson—that the police brushed off Cormier’s death because of his addiction issues.“In my view, the way the police looked at it was: he’s a druggie; there goes another one kinda thing,” she said. “They didn’t care to go through the process afforded to other people.”Greg Cook, an outreach worker with the Toronto drop-in centre Sanctuary, said he and his colleagues regularly conduct their own searches for the next of kin of individuals who have gone missing or died.Pointing to the continued criminalization of the homeless population, Cook said many homeless people distrust the police and are often unwilling to talk to them. On top of this, Cook argues that authorities only respond when there is the potential for accountability, and hypothesizes that because little societal importance is placed on the lives of the homeless, cops feel like they can drop a sudden death investigation without having done much work.“I think that we’ve all probably been in situations where we think, ‘I better do this job well, because if I don’t, somebody’s gonna hold me accountable,’” Cook said. “Often times when you’re poor and don’t have housing, (police) aren’t gonna be held accountable, because you have no power over them.”Bewildered at what happened, Tyson said the Maclean family has launched complaints against the Toronto police and another toward the coroner’s office. He said he is looking for accountability from all the authorities responsible for tending to at-risk populations, as well as those who investigate the deaths of at-risk community members.“These stories, they just keep going on and on and on,” Tyson said.“When does it end? It ends when people in power in these organizations are held accountable for their deaths, because it’s not acceptable in today’s society.”Follow Jake Kivanc on Twitter.Update: Tyson Maclean was Seth’s emergency contact, not a trustee. This story has been updated to reflect that.

Similar to the Maclean case, Cormier’s sister, Wanda Rose, learned about her brother’s death on December 9, 2014, just days after his 52nd birthday and about six months after his actual death. Since June, Rose had become increasingly worried about Cormier, and eventually decided to call 51 Division, when she learned of her brother’s fate.Since that day, Rose said she has never heard again from Toronto police. They offered her little explanation as to why the family wasn’t contacted, she said, nor did they disclose how they decided that his death was a suicide. In her attempts to investigate, Rose was not able to get a hold of the woman said to live in the unit where Gary jumped from, and believes—not unlike Tyson—that the police brushed off Cormier’s death because of his addiction issues.“In my view, the way the police looked at it was: he’s a druggie; there goes another one kinda thing,” she said. “They didn’t care to go through the process afforded to other people.”Greg Cook, an outreach worker with the Toronto drop-in centre Sanctuary, said he and his colleagues regularly conduct their own searches for the next of kin of individuals who have gone missing or died.Pointing to the continued criminalization of the homeless population, Cook said many homeless people distrust the police and are often unwilling to talk to them. On top of this, Cook argues that authorities only respond when there is the potential for accountability, and hypothesizes that because little societal importance is placed on the lives of the homeless, cops feel like they can drop a sudden death investigation without having done much work.“I think that we’ve all probably been in situations where we think, ‘I better do this job well, because if I don’t, somebody’s gonna hold me accountable,’” Cook said. “Often times when you’re poor and don’t have housing, (police) aren’t gonna be held accountable, because you have no power over them.”Bewildered at what happened, Tyson said the Maclean family has launched complaints against the Toronto police and another toward the coroner’s office. He said he is looking for accountability from all the authorities responsible for tending to at-risk populations, as well as those who investigate the deaths of at-risk community members.“These stories, they just keep going on and on and on,” Tyson said.“When does it end? It ends when people in power in these organizations are held accountable for their deaths, because it’s not acceptable in today’s society.”Follow Jake Kivanc on Twitter.Update: Tyson Maclean was Seth’s emergency contact, not a trustee. This story has been updated to reflect that.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement