A very pregnant woman let out a sigh and slumped down on a chair in the registration area of the Vive refugee shelter in Buffalo, New York. Someone set her two young daughters up at a table and they giggled while folding paper airplanes they sent flying around the room.

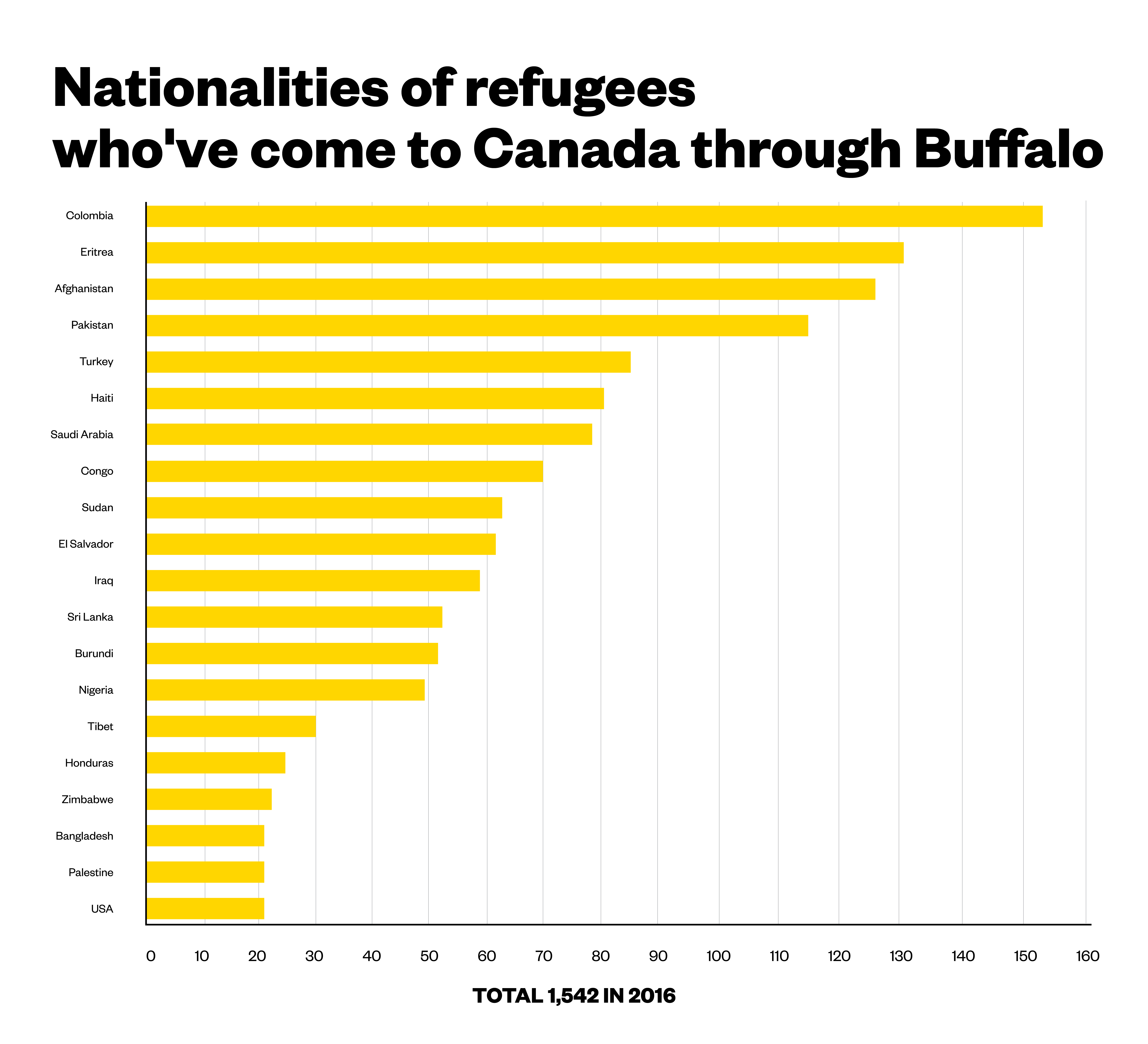

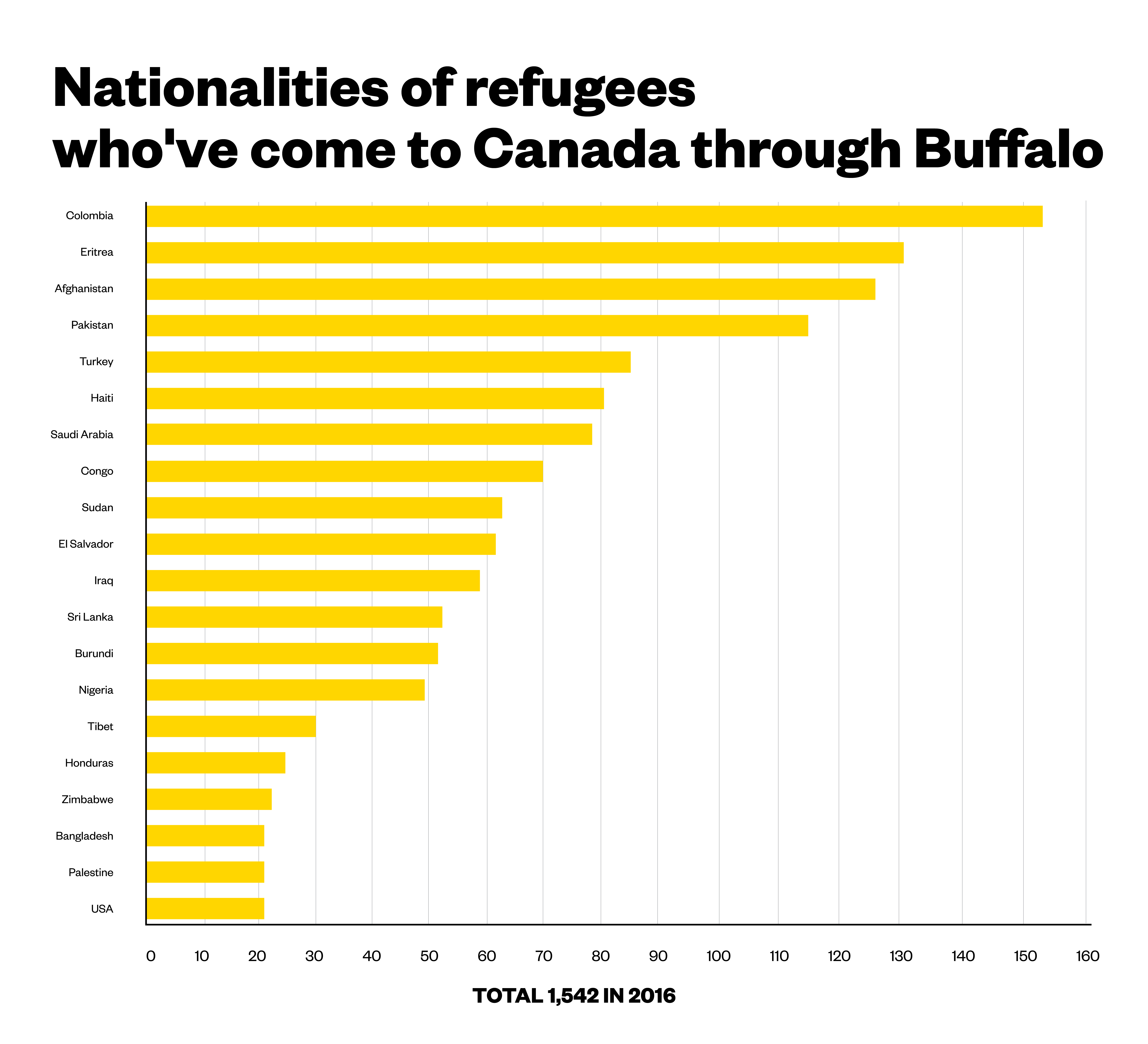

“I wish to get to Canada and have this baby there,” the mother tells the shelter worker while rubbing her stomach. Entering the ninth month of pregnancy, even small movements make her exhausted and uncomfortable. She tugged on the leopard print headscarf under her beret while the shelter’s legal assistant reviewed her passport and medical records.Not wanting to have many details or her name publicized, she explained that she came to the U.S. from Nigeria with her children last summer fleeing violence and threats against her husband, who’s now living as a refugee in Canada. The family got separated because it was easier for him to travel to Canada alone, and she and her children had difficulty getting visitor permits.Vive — Spanish for ‘live’ — was opened in 1985 by nuns who wanted to help the influx of refugees from South America resettle in Canada or the U.S. Now, employees at the building that used to be a Catholic elementary school work with refugees from all over the world with the sole purpose of getting them to Canada through one of the loopholes in a 2004 pact that forces asylum seekers to make their refugee claim in either the U.S. or Canada, whichever one they arrive in first. Prior to that agreement, it was easier for asylum seekers to get over the border. The deal, called the Safe Third Country Agreement, makes it so that if someone arrives on U.S. soil first, for whatever reason, they cannot then travel to Canada to file a refugee claim, and vice versa. This is because both Canada and the U.S. consider each other to be safe enough for refugees, and want to curb the flow of migrants. But because of the agreement, countless refugee claimants get turned away and critics say it pushes people to pursue illegal and dangerous means to get over border.This has become glaringly obvious in recent months. Provinces such as Quebec and Manitoba have seen huge spikes in the number of people, hundreds including young families, risking their lives in the freezing cold to make it across the border from the U.S., which many believe has become all the more precarious under Trump for undocumented migrantsLike everyone else, she waits for the staff to post the daily list of people who have been granted appointments with the Canada Border Services Agency for the following morning. The receptionist prints out the list and pins it to the cork board with a blue sign that states “NO COUSINS,” a reminder that the Safe Third Country Agreement exception only applies to refugee claimants who have immediate family members in Canada, such as a parent, sibling, or spouse.On this day, there are only eight names on the list for appointments the next day: couples and families from Sri Lanka, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Nigeria — Rose hasn’t made it on, yet. Another man checks the list and says he didn’t make it and jokes he’s going to write his name on it himself if he has to.In 2016, Vive alone reports they helped more than 1,540 appointments for people with CBSA, more than 90 percent of whom successfully made it into the country. How many of those people eventually were granted refugee status in Canada in the end is unknown.Mariah Walker, Vive’s Canadian service manager, said she expects that number to rise to more than 2,000 this year in great part because of the climate of fear created by President Trump and his policies that are hostile toward immigrants and refugees. There’s also only one or two other shelters like Vive in the U.S., but they help only a small number of claimants.Those 2,000 people this year will likely be made up of people who might have wanted to stay in the U.S. before the election, but have changed their mind with the shift in immigration policies.Throughout the week, Immigration and Customs Enforcement had stepped up mass raids across America and arrested hundreds of undocumented people for deportation proceedings. Walker has more than 300 new voicemails to get to, likely all from those wanting her services.“Now everyone is saying please help me I can’t stay in the U.S., they are going to deport me,” she explained. “Everyone is so desperate, they are begging for us to find a way to get them to Canada.”While many refugee lawyers and experts in Canada have been pressuring the government to scrap the Safe Third Country Agreement because of these circumstances, Walker said she’s hesitant to go that far, and knows first hand how the four exceptions to the agreement have allowed thousands of refugees to come to Canada.“We don’t usually hear about it until after they get over, and it won’t happen around here in Buffalo because of the geography,” she said. “Once in awhile though, we hear about people who try to cross here, and they get caught and thrown into the detention centre.”Later that afternoon Walker meets with Sam in the registration room. He’s a 58-year-old Syrian citizen who escaped his hometown of Homs in 2012 to Texas to live with his elderly father who held American citizenship. Sam wanted to be referred to by his nickname over concerns that his wife and her family would be killed by government or rebel forces if his location was revealed. Sam was granted a temporary protection visa valid until 2018 to care for his father before he eventually died last fall.

The deal, called the Safe Third Country Agreement, makes it so that if someone arrives on U.S. soil first, for whatever reason, they cannot then travel to Canada to file a refugee claim, and vice versa. This is because both Canada and the U.S. consider each other to be safe enough for refugees, and want to curb the flow of migrants. But because of the agreement, countless refugee claimants get turned away and critics say it pushes people to pursue illegal and dangerous means to get over border.This has become glaringly obvious in recent months. Provinces such as Quebec and Manitoba have seen huge spikes in the number of people, hundreds including young families, risking their lives in the freezing cold to make it across the border from the U.S., which many believe has become all the more precarious under Trump for undocumented migrantsLike everyone else, she waits for the staff to post the daily list of people who have been granted appointments with the Canada Border Services Agency for the following morning. The receptionist prints out the list and pins it to the cork board with a blue sign that states “NO COUSINS,” a reminder that the Safe Third Country Agreement exception only applies to refugee claimants who have immediate family members in Canada, such as a parent, sibling, or spouse.On this day, there are only eight names on the list for appointments the next day: couples and families from Sri Lanka, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Nigeria — Rose hasn’t made it on, yet. Another man checks the list and says he didn’t make it and jokes he’s going to write his name on it himself if he has to.In 2016, Vive alone reports they helped more than 1,540 appointments for people with CBSA, more than 90 percent of whom successfully made it into the country. How many of those people eventually were granted refugee status in Canada in the end is unknown.Mariah Walker, Vive’s Canadian service manager, said she expects that number to rise to more than 2,000 this year in great part because of the climate of fear created by President Trump and his policies that are hostile toward immigrants and refugees. There’s also only one or two other shelters like Vive in the U.S., but they help only a small number of claimants.Those 2,000 people this year will likely be made up of people who might have wanted to stay in the U.S. before the election, but have changed their mind with the shift in immigration policies.Throughout the week, Immigration and Customs Enforcement had stepped up mass raids across America and arrested hundreds of undocumented people for deportation proceedings. Walker has more than 300 new voicemails to get to, likely all from those wanting her services.“Now everyone is saying please help me I can’t stay in the U.S., they are going to deport me,” she explained. “Everyone is so desperate, they are begging for us to find a way to get them to Canada.”While many refugee lawyers and experts in Canada have been pressuring the government to scrap the Safe Third Country Agreement because of these circumstances, Walker said she’s hesitant to go that far, and knows first hand how the four exceptions to the agreement have allowed thousands of refugees to come to Canada.“We don’t usually hear about it until after they get over, and it won’t happen around here in Buffalo because of the geography,” she said. “Once in awhile though, we hear about people who try to cross here, and they get caught and thrown into the detention centre.”Later that afternoon Walker meets with Sam in the registration room. He’s a 58-year-old Syrian citizen who escaped his hometown of Homs in 2012 to Texas to live with his elderly father who held American citizenship. Sam wanted to be referred to by his nickname over concerns that his wife and her family would be killed by government or rebel forces if his location was revealed. Sam was granted a temporary protection visa valid until 2018 to care for his father before he eventually died last fall.

Advertisement

So they eventually ended up at Vive with hopes that its staff would help her family reunite, like they have with nearly 100,000 other asylum seekers they say have quietly flowed through their doors over the last 30 years and into Canada just a short drive north. Ever since the election of President Donald Trump, the shelter has been operating beyond its 150-person capacity non-stop, full of people urgently trying to get out of the country over fears of deportation and discrimination in the U.S.“I need to be there, if only to get some assistance and a better life than this,” said the mother. The legal assistant finished up her paperwork to register them to stay at the shelter until an appointment opens up in a couple weeks with officials at the nearby Canadian border. There, she and her husband will face intense questioning by the border agents who will determine whether they can enter in Canada and begin the refugee claim process. “We’re going to pray,” the woman said before the legal assistant guided her and the girls toward the shelter’s living quarters.“I wish to get to Canada and have this baby there.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

The Vive shelter houses those living in the U.S. who are the exceptions to Safe Third Country Agreement. Most are eligible because they have immediate family members in Canada. The three other exceptions are unaccompanied minors crossing the border, people with valid Canadian immigration or travel status, and refugee claimants who have been charged or found guilty of a criminal offence that could result in the death penalty.—Dozens of people fill Vive’s reception area. On a bookshelf in the backroom sits a Time magazine with Trump’s chief strategist Steve Bannon on the cover. It’s chaos as toddlers run in and out while mothers pace back and forth with babies swinging on their backs. There’s free wifi and most people are texting or whispering into their phones. Down the hall, kids gather in a playroom and residents help prepare lunch in the basement. Most people stay here only for a couple weeks, but others with more complicated cases can end up staying much longer. One Ethiopian woman has lived here for three years with three children, hoping to join her husband in Montreal one day.Another woman, who wished only to be identified as Rose, said she was a police chief in San Salvador but had to flee because of the vicious death threats she was getting from gangsters she helped put in jail. Her children and now ex-husband left for Canada as refugees 10 years ago due to other threats he received, and she hasn’t seen them since. She’s tried to get a visitor visa to Canada, to no avail. After hearing about Vive and fearing for her life more than ever, she decided it would be her last chance to be with her family and start over.“I can’t stay here and need to be there, if only to get some assistance and a better life than this.”

Advertisement

“If this doesn’t work, I will be finished,” Rose said. “I cannot go back home and I can’t stay here.”Canada’s immigration department is not forthcoming with data on how many people have come to Canada through the exceptions to the Safe Third Country Agreement. Spokespeople for the department did not provide numbers requested by VICE News by deadline, and couldn’t clarify whether they even keep such data.One researcher at York University had to purchase numbers from Statistics Canada that showed there were 2,253 refugee claims processed at the border under one of the exceptions to the agreement in 2013. Nearly all of those cases were for people with family members in Canada. No data is readily available for the other years.“I cannot go back home and I can’t stay here.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

“It is scary and the Trump administration is taking actions that if I was an immigrant, I would be extremely terrified of. But at the same time, I wouldn’t say that it’s not necessarily a safe country as a whole anymore,” she said, pointing to the city of Buffalo and the state of New York as examples of places in the country that have been welcoming to newcomers. The mayor flies a flag in front of city hall that reads: “refugees welcome” and has repeatedly vowed to assist anyone affected by Trump’s immigration orders. And it’s because of refugees and immigrants opening businesses, for example, that many parts of the city have seen revitalization in recent years, she explained.“But I would also like Canada to revisit the agreement because although it’s hard to hear people say that my country is no longer safe, it would be an extreme wakeup call to a lot of Americans that things need to get better,” she said. “It’s a highly political move, and I think it would be totally awesome if they did it.”As for asylum seekers who don’t qualify for any of the exceptions to the Safe Third Country Agreement, Walker said she understands they might be more motivated than ever to make the illegal trek into Canada. But the staff there discourages anyone to pursue anything besides the legal immigration channels.“Everyone is so desperate, they are begging for us to find a way to get them to Canada.”

Advertisement

His two adult children left Syria around the same time as him, but took boats from Turkey to Europe and are currently living as refugees in Sweden — but they aren’t allowed to bring their parents there because they are both adults. Once his temporary U.S. status expires, he will have nowhere to go.“I have no home, I lost my job as a civil engineer, I have no car here, and my family is far away,” he said. “So I looked at the map and saw that Buffalo was close to Niagara Falls and the border with Canada. I took a loan from a friend and caught a plane here. Once I got off, the taxi driver recommended I come to Vive.”Sam tells Walker that he has no family in Canada, but still wants her to arrange an appointment with him at the border.“They will send you home, they’ll return you and they’ll detain you,” Walker explained. “You’re already protected in the U.S. for at least another year. I wouldn’t advise you go to Canada. You will also be barred from entering Canada for one year if you’re denied.”But Sam was adamant. “They welcome Syrians like me,” he said. “I want you to please book the appointment.”Walker agrees and walks away. “We won’t deny people who ask us to send their names to the border, but we tell them the reality,” she said.“Once in awhile though, we hear about people who try to cross here, and they get caught and thrown into the detention centre.”