Tribal chair of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, Juan Mancias. PHOTO BY GREG HARMAN

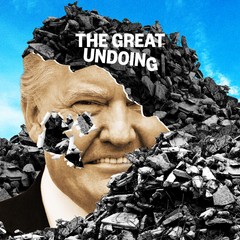

A series that explores what parts of Trump’s legacy will be lasting, and what parts can be quickly undone by a new administration.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Trump's border wall sits to the east of the Eli Jackson Cemetary. Photo courtesy of Sylvia Ramirez

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement