YEKATERINBURG, Russia — When locals come to browse the aisles of Got Comics here in Russia’s fourth-largest city, they’re usually interested in stories featuring American heroes. They rarely look at Russian works, says the shop’s director, Roman Kardakov, but that’s because most Russians don’t even know that a natively Russian comic book scene exists. It’s not surprising, as the community is still shaking off the stigma that came with the Soviet Union banning the books as “enemy culture.” But there’s actually a growing movement of Russian comic artists trying to build an independent scene defined by a love for the art — and separate from the monoliths of Marvel and DC.Yekaterinburg recently hosted a festival dedicated to comics and geek culture called Astro Con. The modest convention was the brainchild of Astro Dogs, a collective dedicated to bridging the culture gap between Russia’s old and young using comics and cartoons. Their idea is to create media that multiple generations can enjoy, citing “Avatar: The Last Airbender” as inspiration. Nikolai Tsepelev, the 19-year-old leader of Astro Dogs, came up with the idea for Astro Con. He said he saw something missing in Russia — a personal convention where ideas are shared — and “rather than complaining, we made it happen,” he said, mirroring the self-reliance of the Russian indie comic scene. When he spoke, he was animated and passionate, reciting a manifesto he’d likely rehearsed at some point. The Astro Dog passion is also evident in the comic the group self-released online. Drawn by Daniil Vetluzhskikh, it’s effervescent and alive. The convention had a similar air. About 1,500 people came to the small hall inside the Museum of Architecture and Design where the event happened, and though the audience skewed to teens and twentysomethings, the crowd was notably varied. There were middle-aged men, cosplayers, schoolkids, and even a furry — all united by unalloyed enjoyment of geek culture. Some even squealed when they saw they could buy a pillow that looked like Miyazaki’s Totoro. Among them, Sergey, a forklift operator, said he “was born with a love for drawing.”Konstantin Dubkov, a comic book artist as well as the founder of the Ural Comics Institute, was also in attendance. He’d recently returned from a U.S. State Department-sponsored, comics-based cultural exchange in America. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund in New York City and a store with a bookcase dedicated to samizdat comics had him longing for such comic-book institutions in Russia. In America, few people he talked to were interested in Russian works, and most wanted to show off American comics. This makes some sense, Dubkov said, because America has a defined school of comics to promote. Europe does, too, but as Dubkov sees it, there is no true Russian school of comics yet.

The convention had a similar air. About 1,500 people came to the small hall inside the Museum of Architecture and Design where the event happened, and though the audience skewed to teens and twentysomethings, the crowd was notably varied. There were middle-aged men, cosplayers, schoolkids, and even a furry — all united by unalloyed enjoyment of geek culture. Some even squealed when they saw they could buy a pillow that looked like Miyazaki’s Totoro. Among them, Sergey, a forklift operator, said he “was born with a love for drawing.”Konstantin Dubkov, a comic book artist as well as the founder of the Ural Comics Institute, was also in attendance. He’d recently returned from a U.S. State Department-sponsored, comics-based cultural exchange in America. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund in New York City and a store with a bookcase dedicated to samizdat comics had him longing for such comic-book institutions in Russia. In America, few people he talked to were interested in Russian works, and most wanted to show off American comics. This makes some sense, Dubkov said, because America has a defined school of comics to promote. Europe does, too, but as Dubkov sees it, there is no true Russian school of comics yet. Over the last 30 years, the attempts to start a comic book scene have been hampered by Russia’s national tumbles. According to Dubkov, there was a small movement developing as early as the ’80s but everything fell apart when Russia defaulted on its debt in 1998. Publishers throughout Russia had to close. Any true interest in Russian comics has only really returned in the past five years.

Over the last 30 years, the attempts to start a comic book scene have been hampered by Russia’s national tumbles. According to Dubkov, there was a small movement developing as early as the ’80s but everything fell apart when Russia defaulted on its debt in 1998. Publishers throughout Russia had to close. Any true interest in Russian comics has only really returned in the past five years. Dubkov was joined at Astro Con by Alexey Gorbut, the main force of Yekaterinburg samizdat comic collective SLAM Comics. Gorbut is the brains behind Cosmobandits, a space opera/Thelma and Louise combination; Vicious Circle, an occult horror comic; and Maha, a comic about a dysfunctional relationship in which a dinosaur suddenly appears. His plots are lively and electric, and the style of his artwork ranges from graffiti-esque to inky comic book realism.

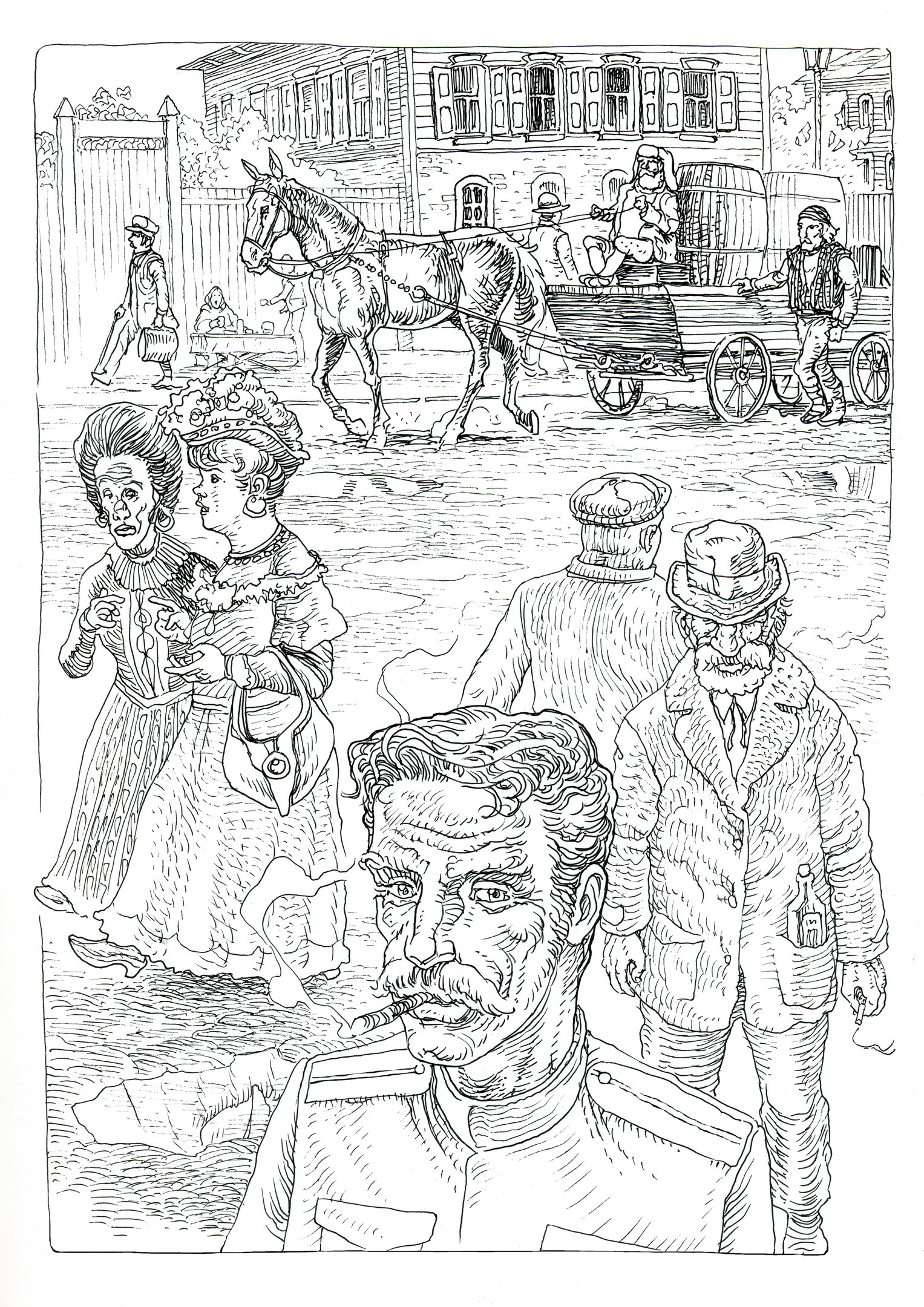

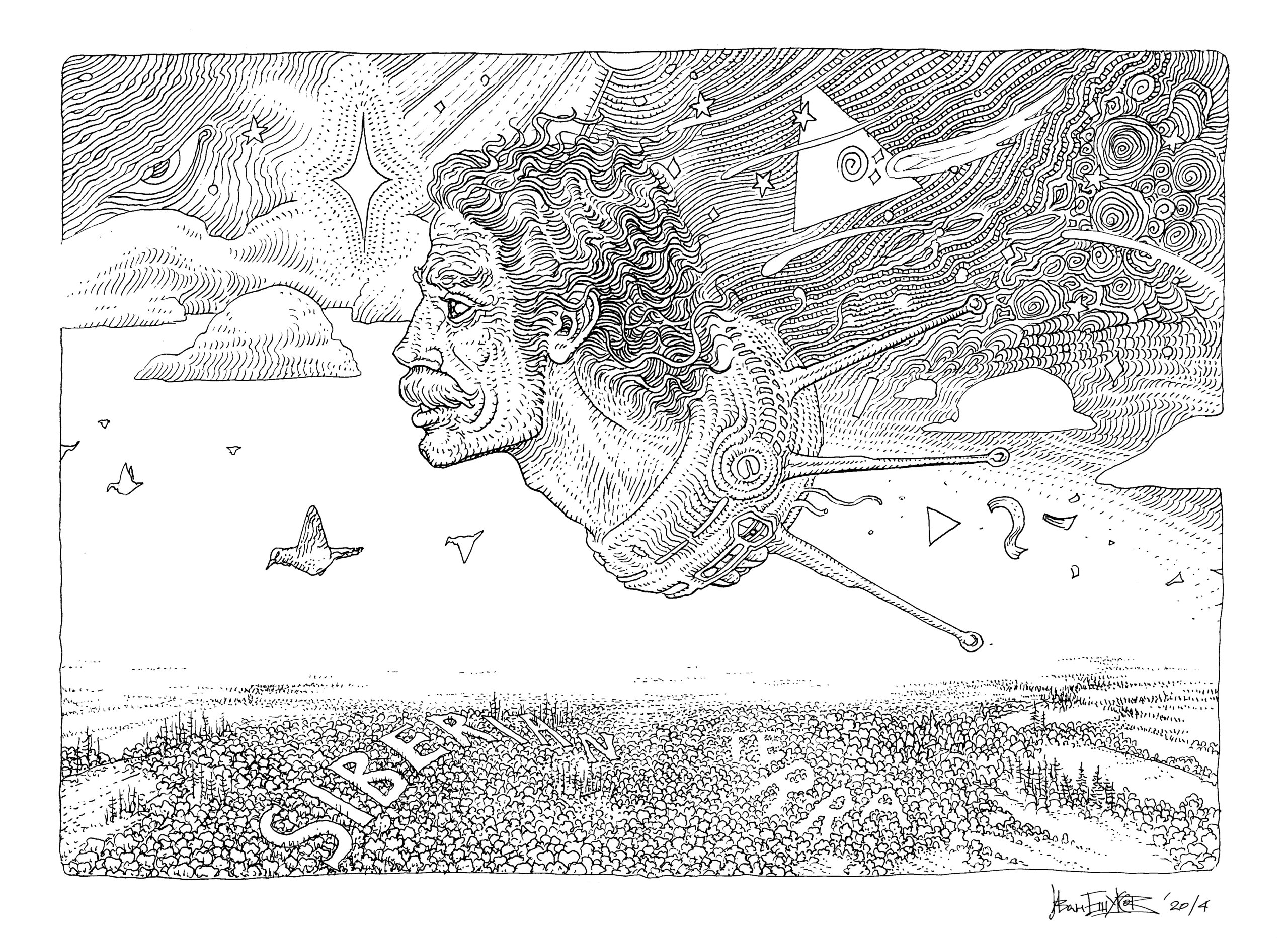

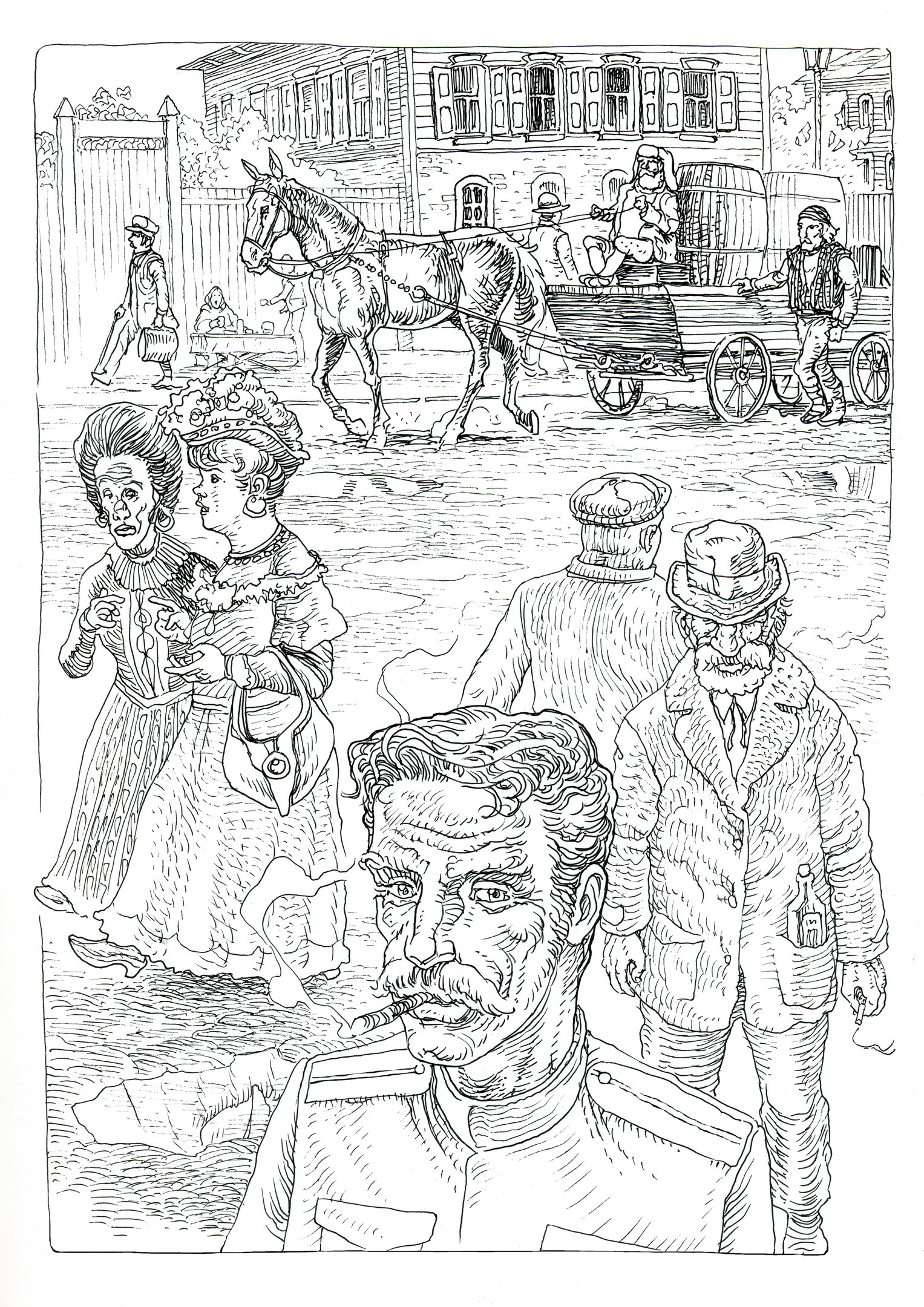

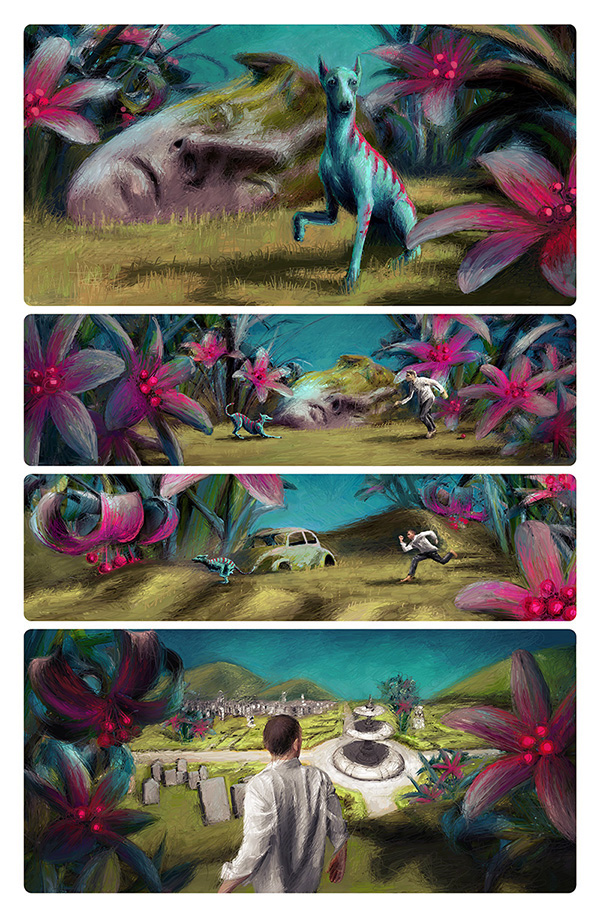

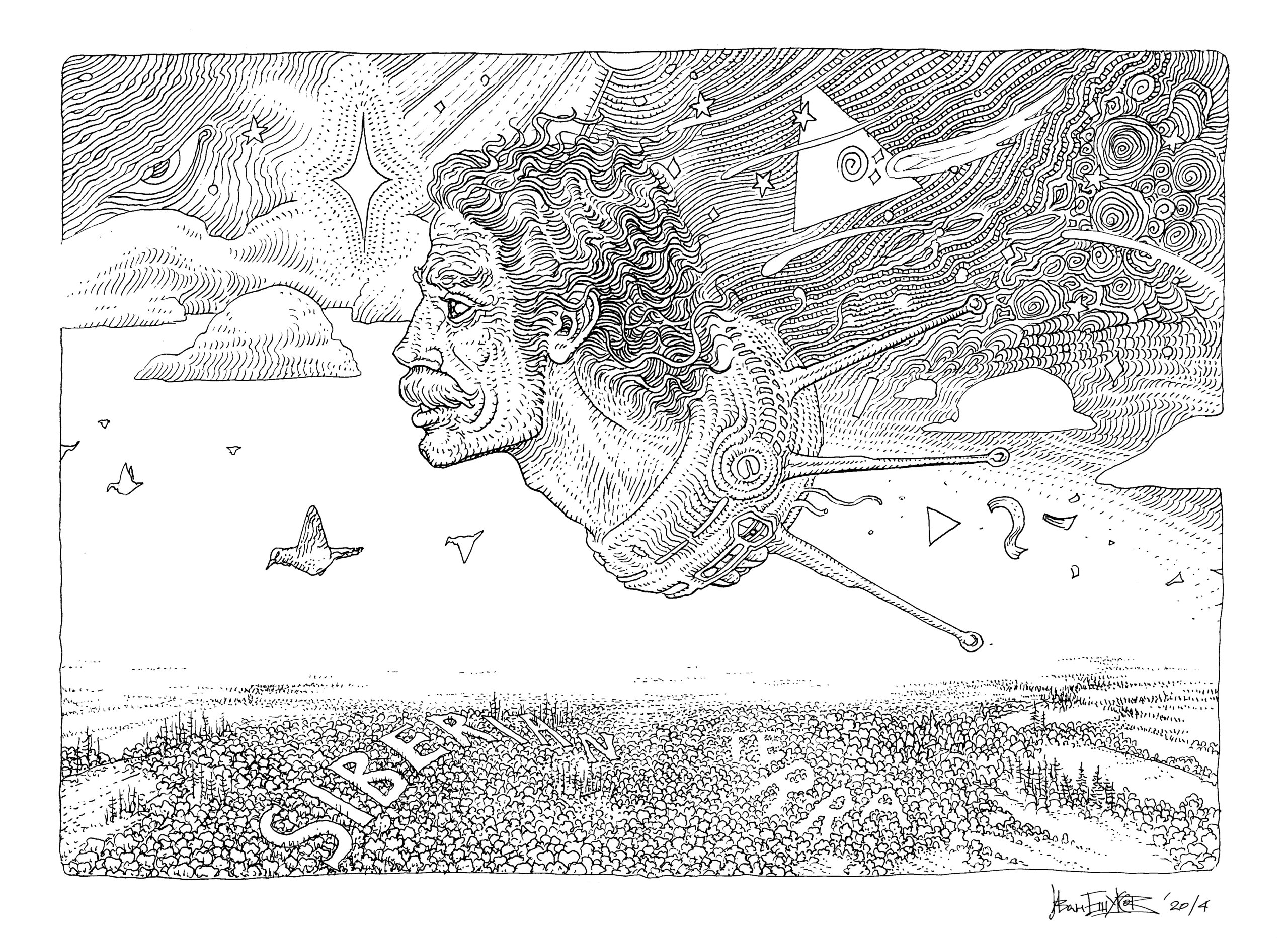

Dubkov was joined at Astro Con by Alexey Gorbut, the main force of Yekaterinburg samizdat comic collective SLAM Comics. Gorbut is the brains behind Cosmobandits, a space opera/Thelma and Louise combination; Vicious Circle, an occult horror comic; and Maha, a comic about a dysfunctional relationship in which a dinosaur suddenly appears. His plots are lively and electric, and the style of his artwork ranges from graffiti-esque to inky comic book realism. There’s no one style in this emerging scene. Ivan Eshukov, an artist in Omsk, Siberia, describes his comic, Borovitsky, as a “mystical detective story.” Numerous fragile lines dominate his style and the plot is slower and more methodical than Gorbut’s uncontainable plots. The story of Borovitsky feels Tolstoyan if Tolstoy had skipped asceticism for cherubim.

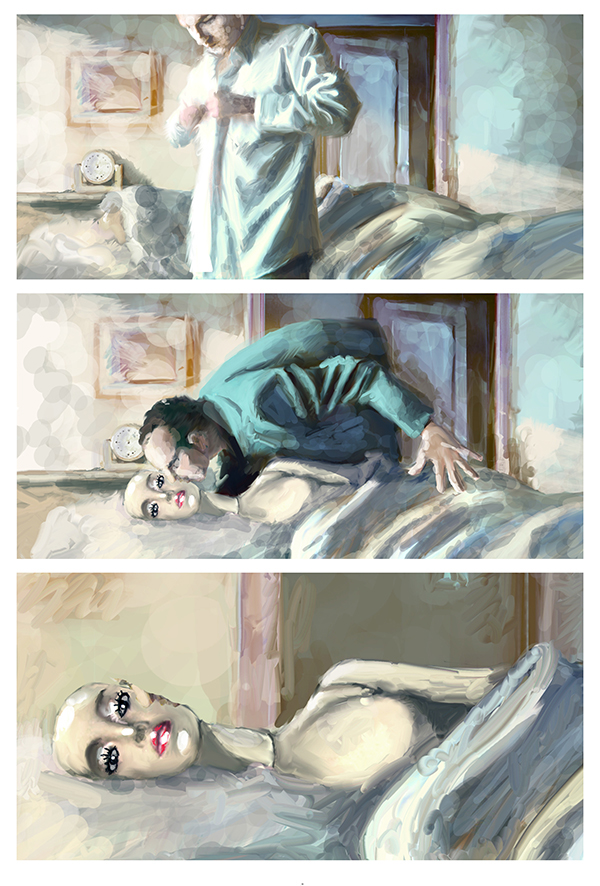

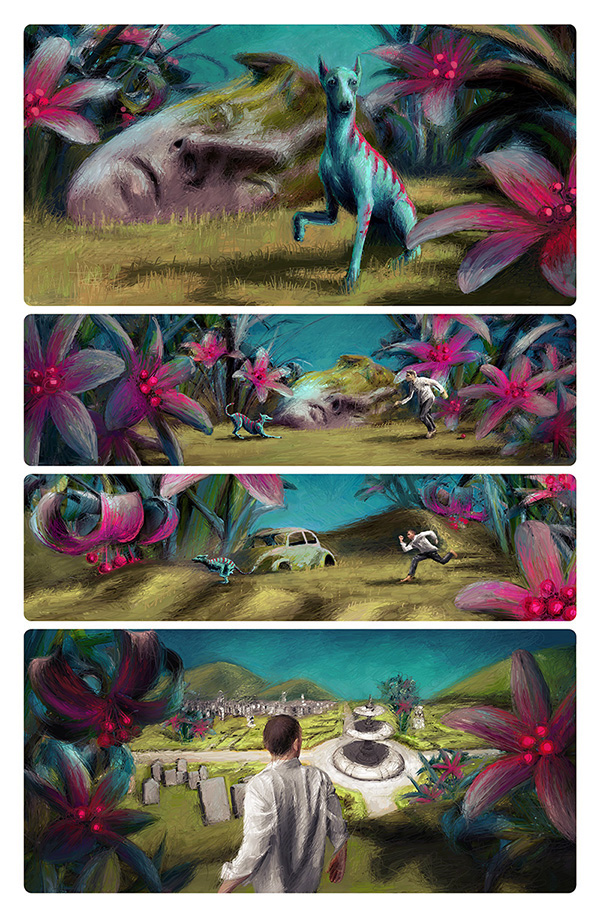

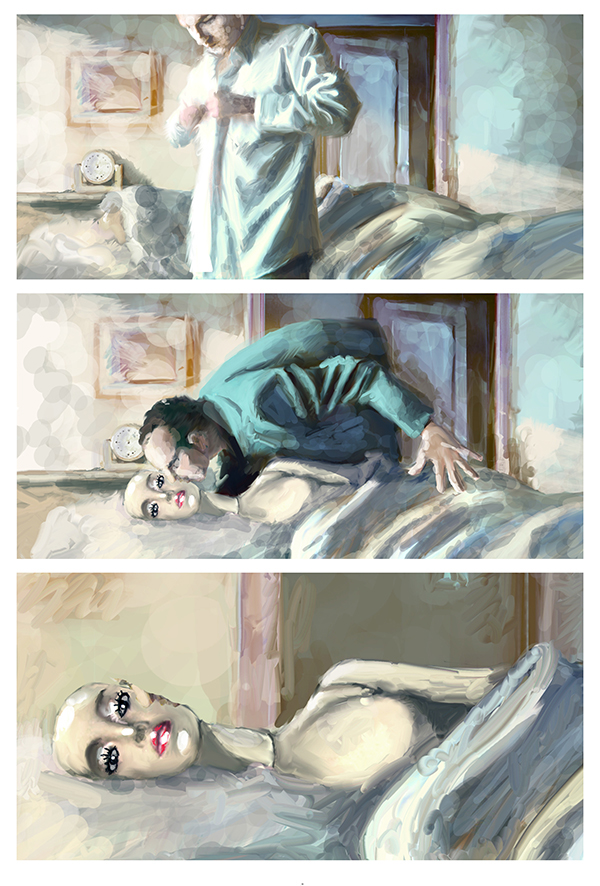

There’s no one style in this emerging scene. Ivan Eshukov, an artist in Omsk, Siberia, describes his comic, Borovitsky, as a “mystical detective story.” Numerous fragile lines dominate his style and the plot is slower and more methodical than Gorbut’s uncontainable plots. The story of Borovitsky feels Tolstoyan if Tolstoy had skipped asceticism for cherubim. Then there is the work of Moscow-based Nikolai Pisarev, which is colorfully dreamlike in both narrative and artwork. Pisarev’s comics, especially “Objects,” are less narrative-based, and more a visual experience — the colors vivid and beautiful, the story largely undefined. When a plot does emerge in his works, such as in “Not Alone,” it feels like arthouse short cinema.

Then there is the work of Moscow-based Nikolai Pisarev, which is colorfully dreamlike in both narrative and artwork. Pisarev’s comics, especially “Objects,” are less narrative-based, and more a visual experience — the colors vivid and beautiful, the story largely undefined. When a plot does emerge in his works, such as in “Not Alone,” it feels like arthouse short cinema. In any discussion of Russian comics, Bubble is one name that always comes up. Bubble is a Russian comic publishing giant which, not coincidentally, opened five years ago. One of its heroes’ origin stories involves meeting Vladimir the Great as he christens Russia, although the comic’s orthodox threads were later given up for a more universally mystical power. When asked about the Russian comic powerhouse, Dubkov dismissed it as a “Marvel clone.”

In any discussion of Russian comics, Bubble is one name that always comes up. Bubble is a Russian comic publishing giant which, not coincidentally, opened five years ago. One of its heroes’ origin stories involves meeting Vladimir the Great as he christens Russia, although the comic’s orthodox threads were later given up for a more universally mystical power. When asked about the Russian comic powerhouse, Dubkov dismissed it as a “Marvel clone.” But even including Marvel-simulacrum Bubble, there’s something that unifies these Russian artists. None of them makes a living as a comic book artist. Ivan Eshukov earns his money painting murals for private interiors. “Comic artists receive some fees for their published work,” he said. “But it isn’t money that you can live on in Russia.” Likewise, Gorbut and Pisarev both work as designers. Dubkov said that even those who work for Bubble have to find work elsewhere.To be an artist in Russia, according to Eshukov, “you just need to love comics.” Gorbut echoed his fellow artist: “With comics, you can convey anything you want. It’s like making a film, only all the work is done without actors, cameramen, and everyone else.”For Dubkov, the answer is even simpler: “I can’t not draw,” he said.

But even including Marvel-simulacrum Bubble, there’s something that unifies these Russian artists. None of them makes a living as a comic book artist. Ivan Eshukov earns his money painting murals for private interiors. “Comic artists receive some fees for their published work,” he said. “But it isn’t money that you can live on in Russia.” Likewise, Gorbut and Pisarev both work as designers. Dubkov said that even those who work for Bubble have to find work elsewhere.To be an artist in Russia, according to Eshukov, “you just need to love comics.” Gorbut echoed his fellow artist: “With comics, you can convey anything you want. It’s like making a film, only all the work is done without actors, cameramen, and everyone else.”For Dubkov, the answer is even simpler: “I can’t not draw,” he said.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement