The Fourth Amendment normally protects Americans’ right to privacy. But using a contested interpretation of the law, a Detroit man was sentenced to 116 years in prison in 2014 for a series of armed robberies.The FBI arrested the man, Timothy Carpenter, largely based on location data from his cell phone that put him within two miles of the crimes. While those records pieced together an exhaustive picture of Carpenter’s every move over nearly half a year, the feds didn’t need a warrant to obtain them because of a legal theory related to the Fourth Amendment known as the “third-party doctrine.”When Carpenter voluntarily turned his cell phone data over to a third party — in this case a cell-phone service provider — he lost any “reasonable expectation of privacy,” the theory goes. And the third-party doctrine doesn’t just apply to cell phone data, but private images, healthcare information, and in some circumstances, even phone calls.The “reasonable expectation of privacy test” stems from a series of mid-20th century Supreme Court decisions related to paper bank records and dialed numbers on landline telephones. But in the nearly four decades since, the information Americans turn over to third parties in the course of regular communications has swelled.For example, the third-party doctrine now affects laws that control the spread of so-called “revenge porn” — nude or explicit photographs posted online without the subject’s consent, often as a way to humiliate an ex. In the past several years, revenge porn statutes have been put on the books in many states. But since the picture was originally given to another person, many of the laws are based upon the victim having a “reasonable expectation of privacy” that the image won’t be posted online. Even though these violations wouldn’t have required warrants, the third-party doctrine limits a victim’s legal recourse.“You can absolutely make the argument that if a victim submitted a photograph to a third party, they didn’t have the privacy expectation,” Blanke said. “It stretches to cover anything.”The “reasonableness” test has even appeared in sexual assault cases. In 2014, the Massachusetts Supreme Court found a man caught taking photos up women’s skirts on the Boston public transit system not guilty because the women lacked a “reasonable expectation of privacy” on a public train. Then-governor Deval Patrick signed anti-Peeping Tom legislation just two days after the decision.A move in Carpenter’s case to redefine the “reasonable expectation of privacy” for the digital age could strengthen harassment victims’ rights under state revenge porn statutes.The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), a federal law safeguarding medical information, has a loophole that allows government agencies to obtain records by subpoena, which requires less legal scrutiny than a warrant.This is “not a great privacy protection,” according to Nathan Wessler, a staff attorney at the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology project who will be arguing on Carpenter’s behalf before the Supreme Court on Wednesday.A 2010 Utah law, however, moved to require warrants before law enforcement could gain access to prescription databases. But that law only governs state searches, not federal investigations.When the DEA challenged the law, a federal court in Utah ruled this August that a warrant isn’t required to search prescription and medical databases. By trusting a doctor with medical information needed to make a diagnosis, a patient “takes the risk . . . that his or her information will be conveyed to the government,” the decision reads.Despite other issues in the case, by framing its decision under the Fourth Amendment and specifically invoking the third-party doctrine, the federal court established precedent that can be used in other privacy cases going forward.Although Carpenter’s upcoming Supreme Court deals exclusively with cell-phone location data, a decision in his favor could limit the government’s ability to conduct searches of sensitive information, like prescription records, as well.The NSA has also used the third-party doctrine to do mass surveillance, like Operation PRISM, its “dragnet” collection of phone records of both Americans and foreign nationals revealed by former contractor Edward Snowden in 2013. Because people voluntarily turn over access to their calls to phone companies, the third-party doctrine applies.“There’s very little that we do in our modern world that isn’t passing through hands of third parties,” said Andrew Crocker, staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which advocates for digital privacy.A specific law, Section 702, permits the NSA to use these programs, which collect electronic communications of foreign targets outside the states. The NSA and other spy agencies, like the FBI and the CIA, then store these records, which include messages written by U.S. citizens. When agents search through this data in their systems, they don’t need a warrant, even when that data belongs to a U.S. citizen.While a federal court has upheld Section 702, privacy watchdogs are still challenging the rule’s constitutionality. And for the first time since the Snowden leaks about the scope of the NSA’s surveillance programs, Congress will have to decide by the end of the year whether to renew Section 702. A group of national security officers sent a bipartisan letter to the president in October arguing for the law’s vitality to security interests.READ: The congressional battle to renew Section 702 surveillanceBy ruling on the scope of what “third party” truly means in the digital age, SCOTUS could throw Section 702 — and the Ninth Circuit Court ruling currently upholding it — into question. Police departments across the country spend tens of thousands of dollars on equipment to monitor activists and track protest gatherings using cell location data often gotten through social media, according to a report by the Brennan Center for Justice last November. These surveillance powers have been turned on Black Lives Matter activists, as well as on protestors at Standing Rock, South Dakota.Right now, cops can gather “metadata,” or information about communications (like location), without a warrant because of the third-party doctrine. That’s the issue at stake in Carpenter’s Supreme Court case. But the contents of those communications — like what’s actually said in a text message — are protected by the Stored Communications Act, which calls for a higher search standard.READ: How cops hack into your phone without a warrantWhen law enforcement use data gathered by tech companies without a warrant, that puts the businesses in an awkward position. For Carpenter’s upcoming Supreme Court case, a group of major tech firms also filed a brief, which are generally written in support of one side over the other.While the firms — including Google, Apple, Airbnb, Dropbox, and Facebook — formally backed neither side in the case, they argued “inflexible doctrines” that sweepingly eliminate any expectation of privacy for data that already exists or that of the future “are not sustainable.”Still, Carpenter’s lawyers aren’t calling for the Supreme Court to revoke the third-party doctrine entirely. Instead, they’re just asking for an update.“If the Court agrees that longer-term cell location records are protected, then it will be easier in the future to figure out protected versus unprotected categories – the health data in a smartwatch, or information about the interior of a smart home, for example, may be protected, while public Twitter messages may not be protected,” the ACLU’s Wessler explained ahead of his oral arguments on Wednesday. “That’s the type of analysis that will happen.”“If they change the law even that much, it is a really big deal,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Crocker added. “This has potential to be one of biggest digital privacy rulings in a really long time.”Editor’s note 11/28/17 4:58 p.m. ET: A previous version of this piece incorrectly identified Jody Blanke’s gender in one instance.

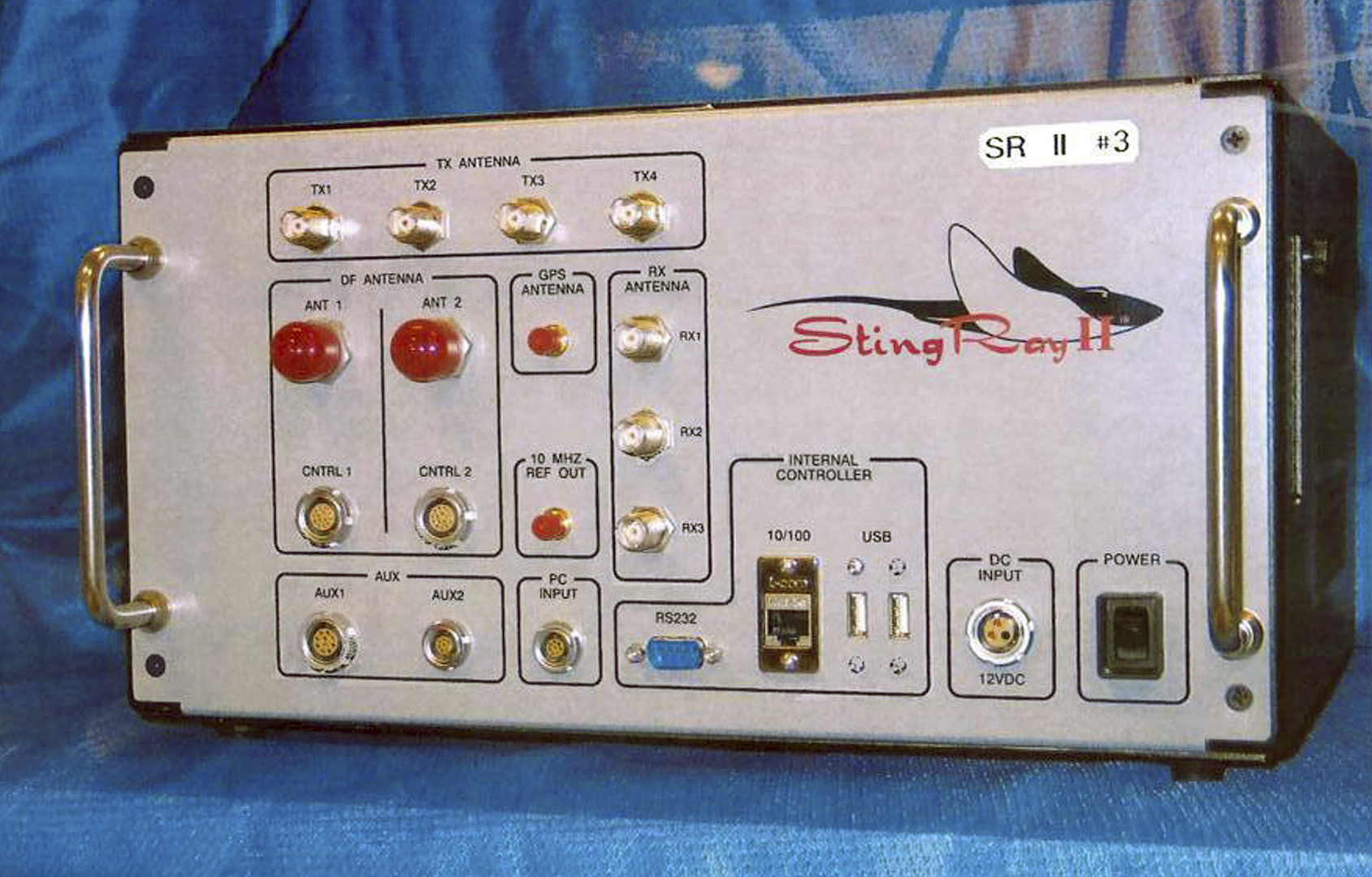

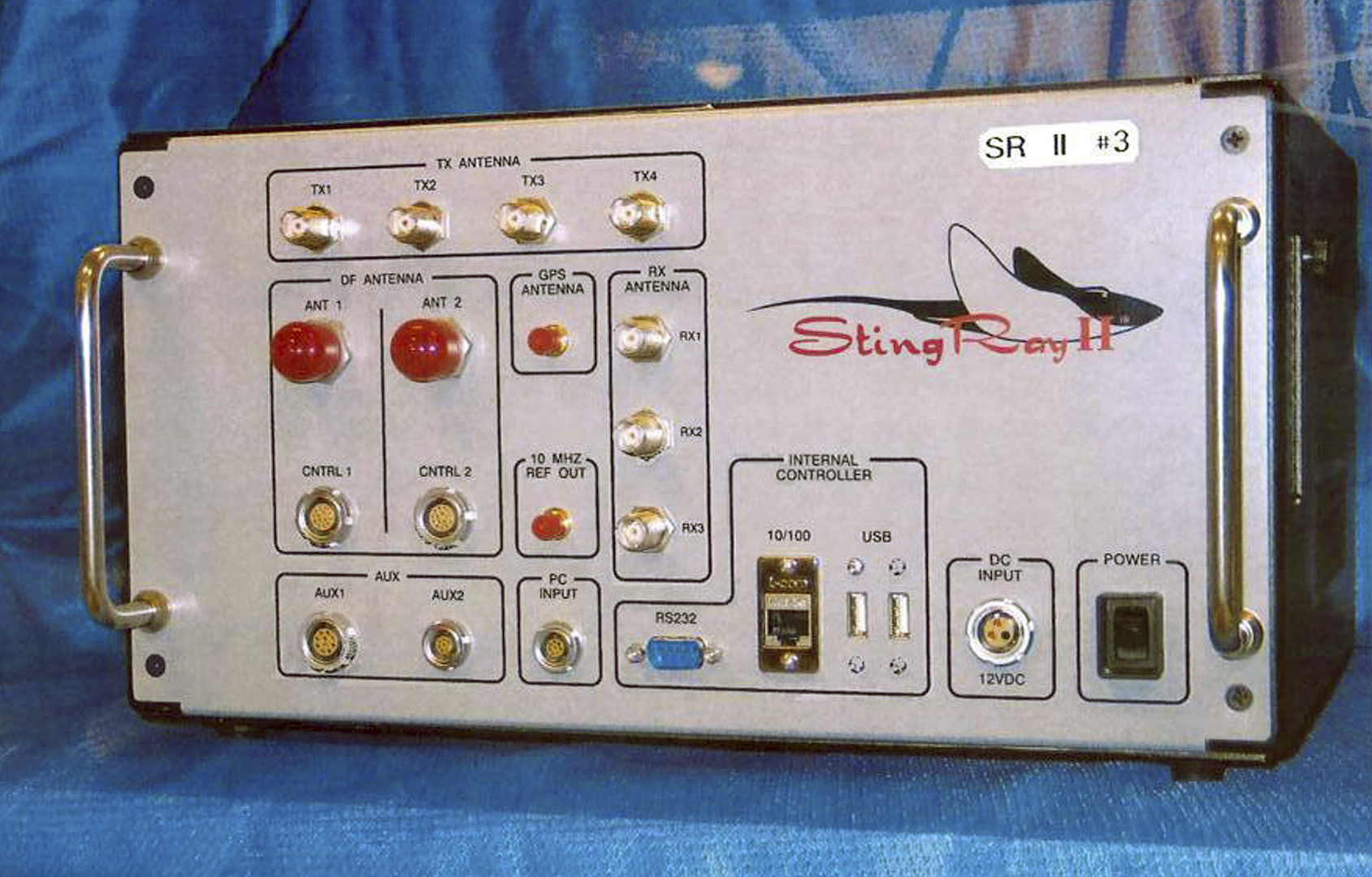

Police departments across the country spend tens of thousands of dollars on equipment to monitor activists and track protest gatherings using cell location data often gotten through social media, according to a report by the Brennan Center for Justice last November. These surveillance powers have been turned on Black Lives Matter activists, as well as on protestors at Standing Rock, South Dakota.Right now, cops can gather “metadata,” or information about communications (like location), without a warrant because of the third-party doctrine. That’s the issue at stake in Carpenter’s Supreme Court case. But the contents of those communications — like what’s actually said in a text message — are protected by the Stored Communications Act, which calls for a higher search standard.READ: How cops hack into your phone without a warrantWhen law enforcement use data gathered by tech companies without a warrant, that puts the businesses in an awkward position. For Carpenter’s upcoming Supreme Court case, a group of major tech firms also filed a brief, which are generally written in support of one side over the other.While the firms — including Google, Apple, Airbnb, Dropbox, and Facebook — formally backed neither side in the case, they argued “inflexible doctrines” that sweepingly eliminate any expectation of privacy for data that already exists or that of the future “are not sustainable.”Still, Carpenter’s lawyers aren’t calling for the Supreme Court to revoke the third-party doctrine entirely. Instead, they’re just asking for an update.“If the Court agrees that longer-term cell location records are protected, then it will be easier in the future to figure out protected versus unprotected categories – the health data in a smartwatch, or information about the interior of a smart home, for example, may be protected, while public Twitter messages may not be protected,” the ACLU’s Wessler explained ahead of his oral arguments on Wednesday. “That’s the type of analysis that will happen.”“If they change the law even that much, it is a really big deal,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Crocker added. “This has potential to be one of biggest digital privacy rulings in a really long time.”Editor’s note 11/28/17 4:58 p.m. ET: A previous version of this piece incorrectly identified Jody Blanke’s gender in one instance.

Advertisement

Carpenter’s lawyers, however, will argue before the Supreme Court on Wednesday that law enforcement violated his Constitutional right to privacy by not obtaining a warrant before searching his cell phone data. The third-party doctrine, they say, is outdated and too narrow to suit today’s ever-changing technologies.“Most scholars agree that privacy is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon,” said Jody Blanke, a veteran professor of computer privacy law at Atlanta’s Mercer University. He signed an amicus brief in support of Carpenter. “You can disclose information to a third party and still have a reasonable expectation of privacy.”A decision in favor of Carpenter, however, would limit law enforcement’s access to information that could help them prevent or solve crime. Regardless, the case will either drastically expand or limit Americans’ right to privacy in the digital age.“There’s very little that we do in our modern world that isn’t passing through hands of third parties.”

Revenge porn

Advertisement

Prescription and medical records

Advertisement

NSA surveillance

Advertisement

Protest monitoring

Advertisement