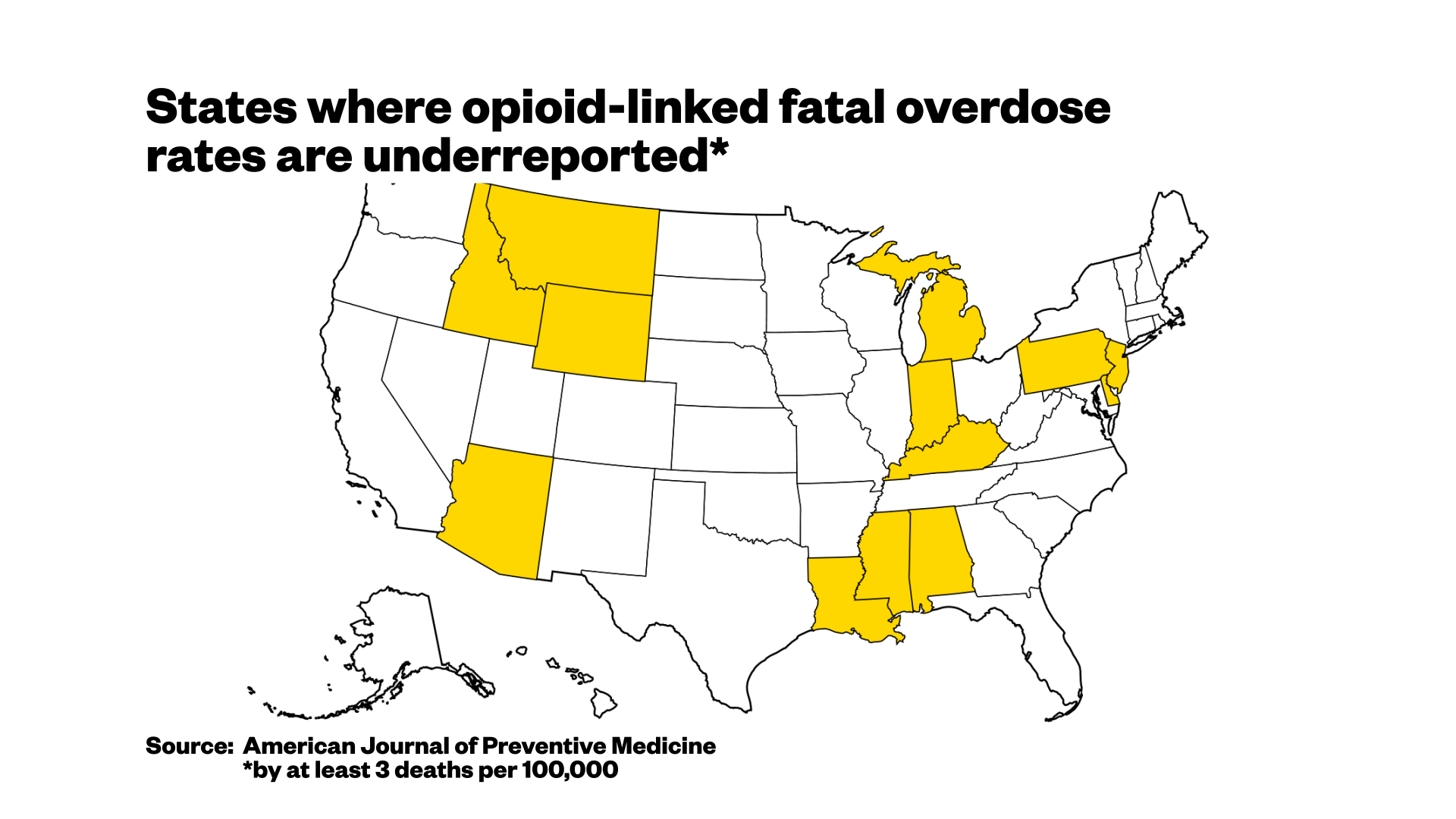

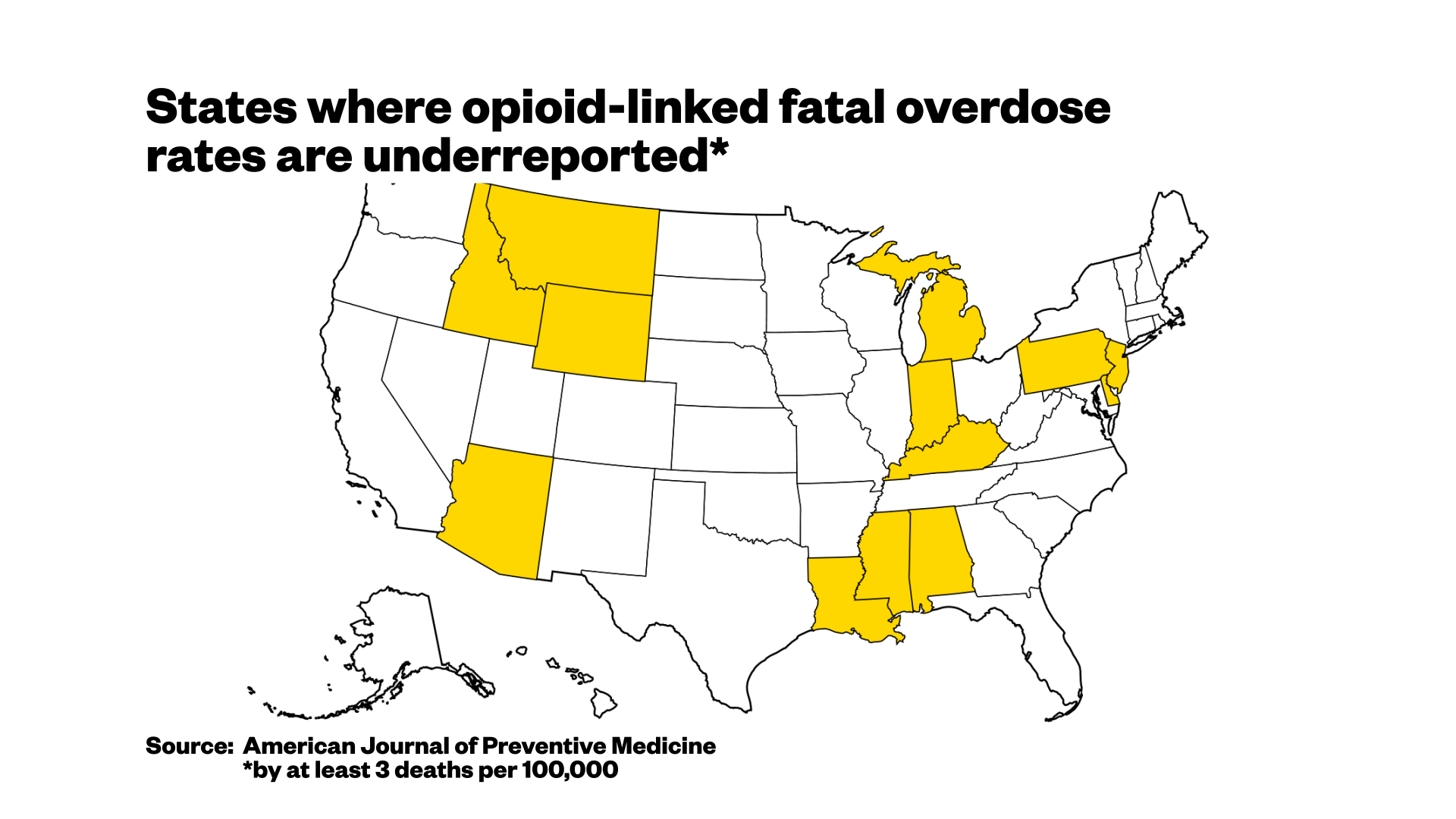

Official statistics on opioid-linked deaths in the U.S. are already pretty bleak. Rates of opioid overdoses spiked 200 percent between 2000 and 2014, while more than 33,000 people died of overdose deaths involving opioids in 2015, according to the CDC.Government agencies like the CDC often track opioid-related deaths based on death certificates, but researchers have long argued that these numbers are still underreported. One economist may have found a way to help fix that issue — and his study, published Monday in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, suggests that deadly overdoses involving opioids could be even more common: In 2014, the study suggests, opioid-involved fatal overdose rates may have been 24 percent higher than officials previously believed.Officially, in 2014, the nationwide mortality rate of opioid-related overdoses was 9 deaths per 100,000 people. But according to the new study, that number should be closer to 11 deaths per 100,000 people — especially since some states might be dramatically underestimating their opioid-linked fatal overdose rates.Because local practices around filling out death certificates can vary widely, it’s easy for errors or oversights to arise. Plus, if workers don’t have definitive proof that opioids are involved, they might want to avoid stereotyping a patient and not list the specific drug involved. According to the study, more than a quarter of drug overdose death certificates didn’t identify the drug involved in 2008; in 2014, only a fifth did.“My view is, before we can have good policy, we need to understand what the facts are,” Christopher Ruhm, the study’s author and a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia, told VICE News. He’s been interested in studying drug-related deaths for years, but found that incomplete death certificates complicated his ability to get accurate statistics. “That just seemed very unsatisfactory,” he said. Ruhm used death certificates to examine all 50 states’ drug-involved fatal overdose rates in both 2008 and 2014. He first looked at death certificates that did specify what type of drug was involved and identified which demographic characteristics — such as gender, race, and education level, to name a few — occurred most frequently in deaths from known opioid-related overdoses. Using those characteristics, Ruhm then crafted “prediction equations” to calculate the probability that opioids or heroin were involved in an individual’s death.While not everybody who fits the profile of an opioid overdose necessarily dies of an opioid overdose, Abraham Flaxman, a researcher at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, said that “tough number crunching” is necessary to understand the scope of the opioid epidemic. “If you’re going to use this information to try to find out just how big this big problem is, I think it’s a good way to get going,” said Flaxman, who has also studied misreporting on death certificates.According to Ruhm’s model, many states might be dramatically underestimating how many people die of opioid-related overdoses. For example, only 8.5 deaths per every 100,000 people were officially linked to opioids in Pennsylvania in 2014, according to Ruhm’s analysis of death certificates. But his model predicted that 17.8 deaths out of every 100,000 people were, in fact, caused by opioids — more than doubling previous estimates. Rates of opioid-related overdoses in Louisiana, Alabama, and Indiana also doubled using Ruhm’s model.

Ruhm used death certificates to examine all 50 states’ drug-involved fatal overdose rates in both 2008 and 2014. He first looked at death certificates that did specify what type of drug was involved and identified which demographic characteristics — such as gender, race, and education level, to name a few — occurred most frequently in deaths from known opioid-related overdoses. Using those characteristics, Ruhm then crafted “prediction equations” to calculate the probability that opioids or heroin were involved in an individual’s death.While not everybody who fits the profile of an opioid overdose necessarily dies of an opioid overdose, Abraham Flaxman, a researcher at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, said that “tough number crunching” is necessary to understand the scope of the opioid epidemic. “If you’re going to use this information to try to find out just how big this big problem is, I think it’s a good way to get going,” said Flaxman, who has also studied misreporting on death certificates.According to Ruhm’s model, many states might be dramatically underestimating how many people die of opioid-related overdoses. For example, only 8.5 deaths per every 100,000 people were officially linked to opioids in Pennsylvania in 2014, according to Ruhm’s analysis of death certificates. But his model predicted that 17.8 deaths out of every 100,000 people were, in fact, caused by opioids — more than doubling previous estimates. Rates of opioid-related overdoses in Louisiana, Alabama, and Indiana also doubled using Ruhm’s model. Nationwide, Ruhm suggests that opioids overall were responsible for 24 percent more fatal overdoses in 2014 than previously believed; heroin specifically led to 22 percent more fatal overdoses.At the same time, however, states like Ohio and Kentucky might be overstating the rise in opioid fatal overdose rates between 2008 and 2014, since death certificates in those states have begun to more frequently specify what drugs led to individuals’ overdoses.“When you’re specifying drugs more completely in a later year, if nothing else changed, you tend to see an increase in the number of drug deaths,” Ruhm explained. “But actually some of that increase — or maybe a lot of that increase — is just due to the better reporting.”While the study’s numbers may sound eye-popping, it’s not the first time researchers have found that death certificates can be staggeringly inaccurate. Last year, Flaxman was part of a team of University of Washington researchers who found evidence indicating that deaths caused by mental illness, drugs, and alcohol had spiked by nearly 200 percent over the past 30 years — much higher than official statistics would suggest.If anything, Flaxman said, Ruhm’s approach is an underestimate. Workers mark down overdoses in a variety of ways on death certificates, and Ruhm only included some in his study. Plus, Flaxman added, “This is all about 2014, so if you look at trends, it’s probably worse today.”

Nationwide, Ruhm suggests that opioids overall were responsible for 24 percent more fatal overdoses in 2014 than previously believed; heroin specifically led to 22 percent more fatal overdoses.At the same time, however, states like Ohio and Kentucky might be overstating the rise in opioid fatal overdose rates between 2008 and 2014, since death certificates in those states have begun to more frequently specify what drugs led to individuals’ overdoses.“When you’re specifying drugs more completely in a later year, if nothing else changed, you tend to see an increase in the number of drug deaths,” Ruhm explained. “But actually some of that increase — or maybe a lot of that increase — is just due to the better reporting.”While the study’s numbers may sound eye-popping, it’s not the first time researchers have found that death certificates can be staggeringly inaccurate. Last year, Flaxman was part of a team of University of Washington researchers who found evidence indicating that deaths caused by mental illness, drugs, and alcohol had spiked by nearly 200 percent over the past 30 years — much higher than official statistics would suggest.If anything, Flaxman said, Ruhm’s approach is an underestimate. Workers mark down overdoses in a variety of ways on death certificates, and Ruhm only included some in his study. Plus, Flaxman added, “This is all about 2014, so if you look at trends, it’s probably worse today.”

Advertisement

Advertisement