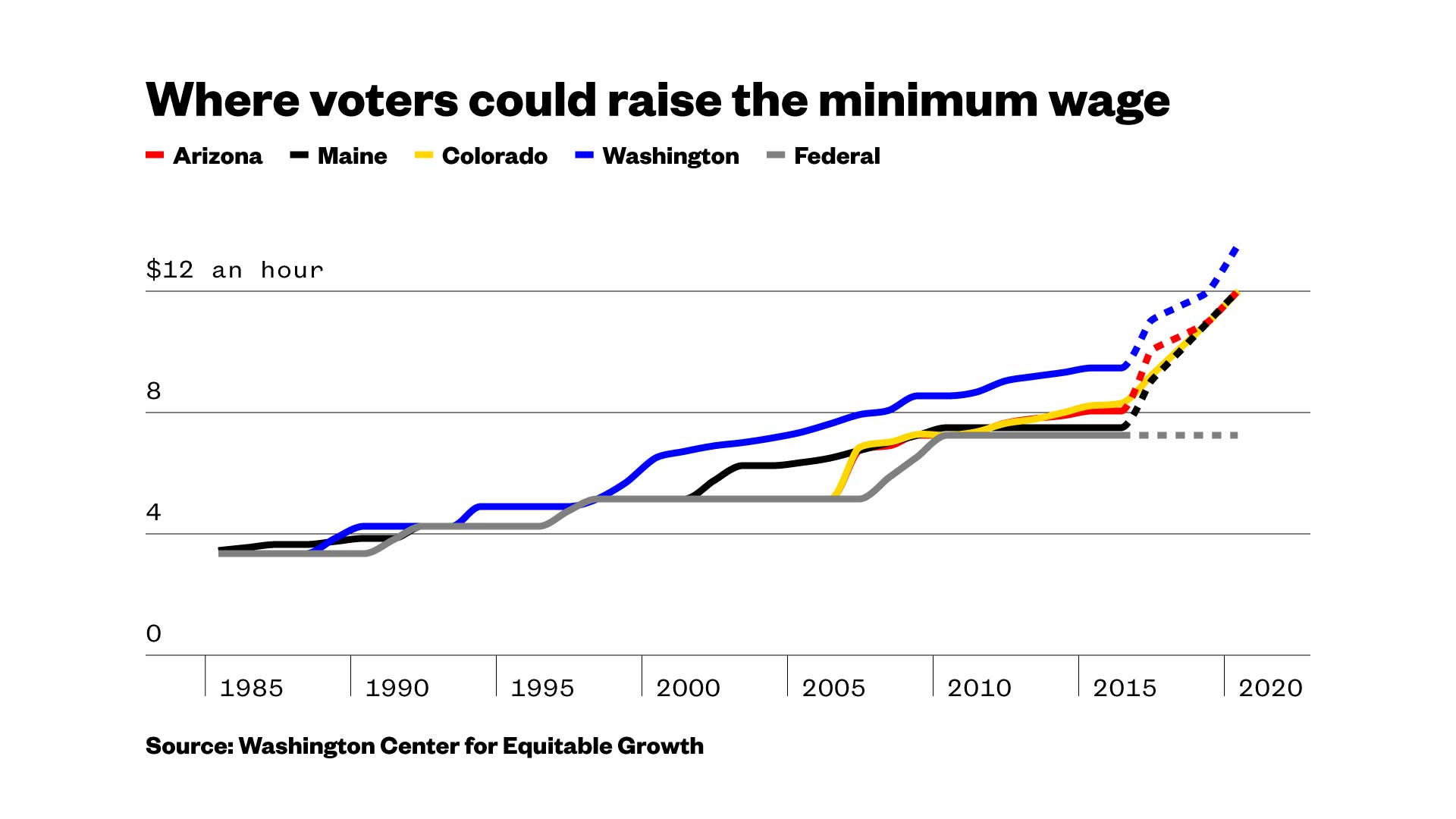

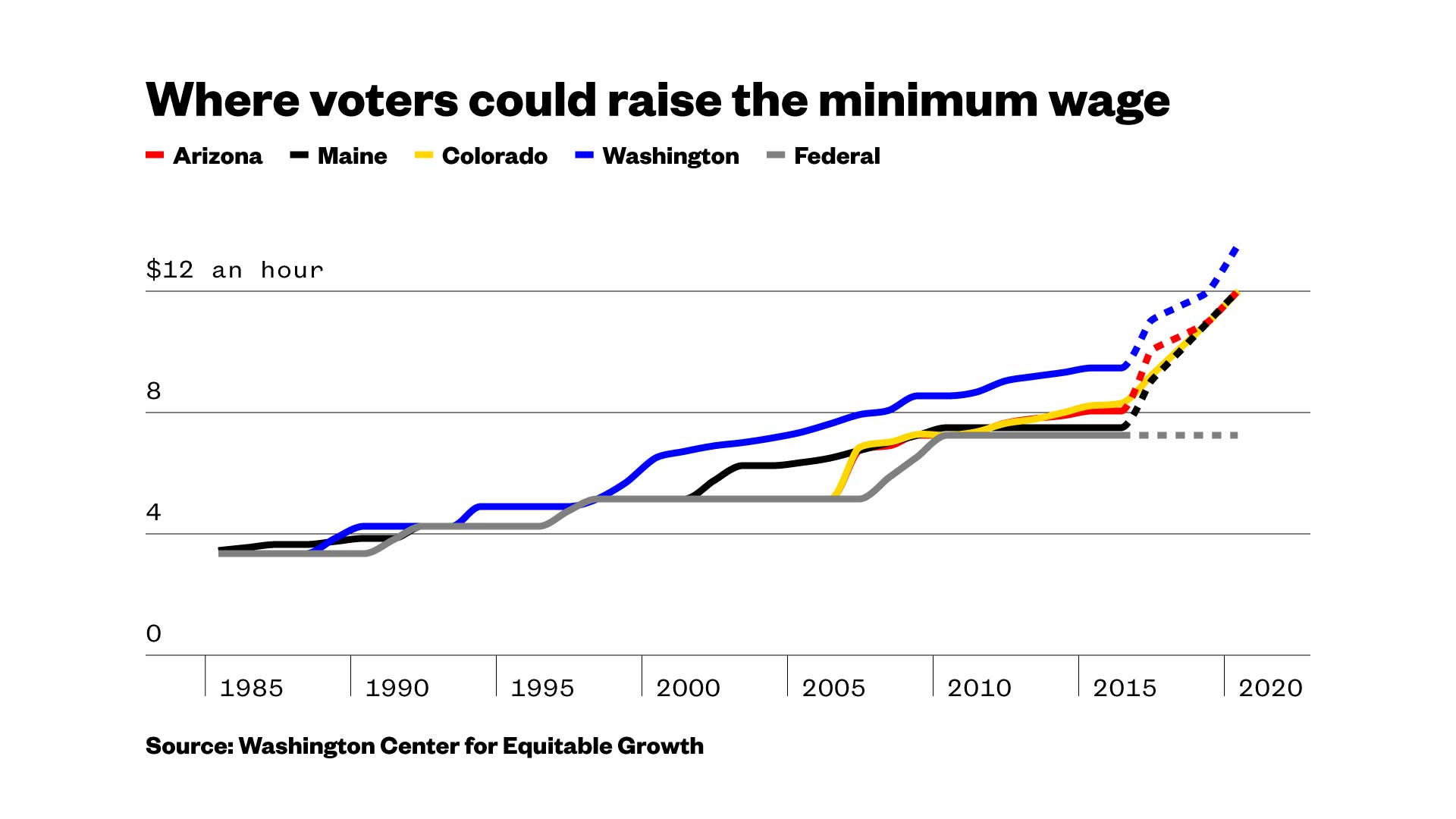

Americans will likely vote next week to roll back decades of increasing economic inequality that has severely undermined the country’s cherished self-image as a meritocratic, middle-class nation. But this vote won’t be for president.With the U.S. economy on the upswing, voters in Arizona, Colorado, Maine, and Washington are set to vote on increases to those states’ minimum wages by as much as 60 percent over the next few years, adding to nationwide momentum that has lifted wages for low-income workers significantly. “In a time of prosperity and high profit and high stock market, there’s a demand to raise the minimum wage,” said Michael Reich, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies the minimum wage. “Whenever times are good, then there’s less fear or risk by policymakers about putting those through.”Along with surging executive pay, the decline of unionization, and the disappearance of U.S. manufacturing jobs, economists view the stagnant value of the U.S. federal minimum wage as an important contributor to increasing inequality over the last three decades. In inflation-adjusted terms, the federal minimum wage is now more than 20 percent lower than it was in 1980. (Back then the minimum wage of $3.10 an hour had the same buying power as roughly $9 in 2016 dollars.)And even though the federal government raised the minimum wage in 2009, to $7.25 to from $6.55, it has been completely flat since, prompting several states to move ahead with wage increases of their own.In 2015, 24 states and the District of Columbia either implemented or phased in wage increases, according to data compiled by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Among them were deeply Republican states such as Nebraska and South Dakota and blue bastions such as Massachusetts and Maryland.There’s a simple reason why both red and blue states are willing to vote to lift wages for low-income workers. And it’s the same reason both Republican nominee Donald Trump and Democratic standard-bearer Hillary Clinton have said the minimum wage should rise. Raising the minimum wage is overwhelmingly popular.Some 73 percent of Americans polled by the Pew Research Center in December 2015 favored raising the minimum wage. In August, Pew asked Americans if they’d favor raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour from the current $7.25. Roughly 52 percent did, though that majority came from overwhelming support from Democratic voters.Even in the midst of a tumultuous and divisive election year, support for a higher minimum wage remains strong. In Colorado, some 55 percent of voters support Amendment 70, which would raise the state’s minimum wage to $12 an hour by 2020. (About 42 percent oppose the measure, according to a poll published by the Denver Post in September.)A similar proposal in Maine has the support of 6 in 10 likely voters in the state, according to the Portland Press Herald. In traditionally conservative Arizona, more than 58 percent support a proposition to raise the minimum wage from $8.05 to $10 an hour in January, rising to $12 an hour by 2020, according to results of a recent poll. Likewise, support for a proposal to raise Washington’s minimum wage to $13.50 by 2020 has support hovering around 57 percent according to somewhat limited polling.If the measures pass, these states will add to a recent upswing in wages for low-income workers. Last year, U.S. median household incomes jumped 5.2 percent, the largest increase on record and the first jump since 2007, the year before the financial crisis hit.What’s more, incomes for the lowest-earning 20 percent of American households were up even more, rising 6.3 percent. Poverty dropped sharply in 2015, with the number of people living in poverty falling by 3.5 million.And last year, major companies — led by Wal-Mart, the country’s largest private-sector employer — announced a series of voluntary pay increases.The fact that private-sector employers felt confident enough to increase wages suggests that the timing might be right for further attempts to boost pay. (After all, if the corporations could afford pay increases, they wouldn’t have moved to boost wages.)In a recent research report, economists from Standard & Poor’s wrote that the economic benefits of a “measured” increase in the minimum wage would prove beneficial to a quite healthy U.S. economy.“If there’s ever been a good time to give America a raise, it’s now,” they wrote.

“In a time of prosperity and high profit and high stock market, there’s a demand to raise the minimum wage,” said Michael Reich, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies the minimum wage. “Whenever times are good, then there’s less fear or risk by policymakers about putting those through.”Along with surging executive pay, the decline of unionization, and the disappearance of U.S. manufacturing jobs, economists view the stagnant value of the U.S. federal minimum wage as an important contributor to increasing inequality over the last three decades. In inflation-adjusted terms, the federal minimum wage is now more than 20 percent lower than it was in 1980. (Back then the minimum wage of $3.10 an hour had the same buying power as roughly $9 in 2016 dollars.)And even though the federal government raised the minimum wage in 2009, to $7.25 to from $6.55, it has been completely flat since, prompting several states to move ahead with wage increases of their own.In 2015, 24 states and the District of Columbia either implemented or phased in wage increases, according to data compiled by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Among them were deeply Republican states such as Nebraska and South Dakota and blue bastions such as Massachusetts and Maryland.There’s a simple reason why both red and blue states are willing to vote to lift wages for low-income workers. And it’s the same reason both Republican nominee Donald Trump and Democratic standard-bearer Hillary Clinton have said the minimum wage should rise. Raising the minimum wage is overwhelmingly popular.Some 73 percent of Americans polled by the Pew Research Center in December 2015 favored raising the minimum wage. In August, Pew asked Americans if they’d favor raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour from the current $7.25. Roughly 52 percent did, though that majority came from overwhelming support from Democratic voters.Even in the midst of a tumultuous and divisive election year, support for a higher minimum wage remains strong. In Colorado, some 55 percent of voters support Amendment 70, which would raise the state’s minimum wage to $12 an hour by 2020. (About 42 percent oppose the measure, according to a poll published by the Denver Post in September.)A similar proposal in Maine has the support of 6 in 10 likely voters in the state, according to the Portland Press Herald. In traditionally conservative Arizona, more than 58 percent support a proposition to raise the minimum wage from $8.05 to $10 an hour in January, rising to $12 an hour by 2020, according to results of a recent poll. Likewise, support for a proposal to raise Washington’s minimum wage to $13.50 by 2020 has support hovering around 57 percent according to somewhat limited polling.If the measures pass, these states will add to a recent upswing in wages for low-income workers. Last year, U.S. median household incomes jumped 5.2 percent, the largest increase on record and the first jump since 2007, the year before the financial crisis hit.What’s more, incomes for the lowest-earning 20 percent of American households were up even more, rising 6.3 percent. Poverty dropped sharply in 2015, with the number of people living in poverty falling by 3.5 million.And last year, major companies — led by Wal-Mart, the country’s largest private-sector employer — announced a series of voluntary pay increases.The fact that private-sector employers felt confident enough to increase wages suggests that the timing might be right for further attempts to boost pay. (After all, if the corporations could afford pay increases, they wouldn’t have moved to boost wages.)In a recent research report, economists from Standard & Poor’s wrote that the economic benefits of a “measured” increase in the minimum wage would prove beneficial to a quite healthy U.S. economy.“If there’s ever been a good time to give America a raise, it’s now,” they wrote.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement