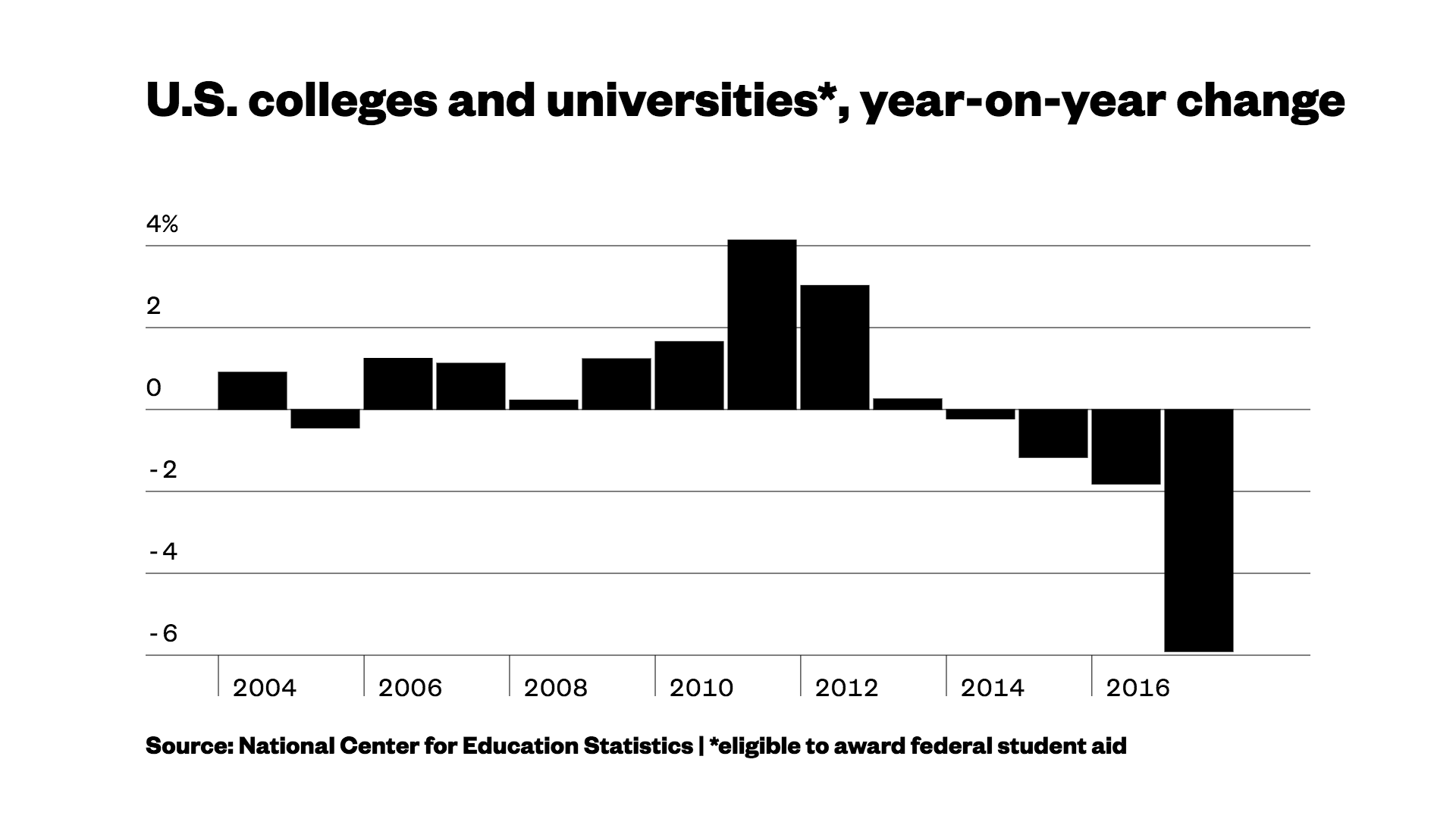

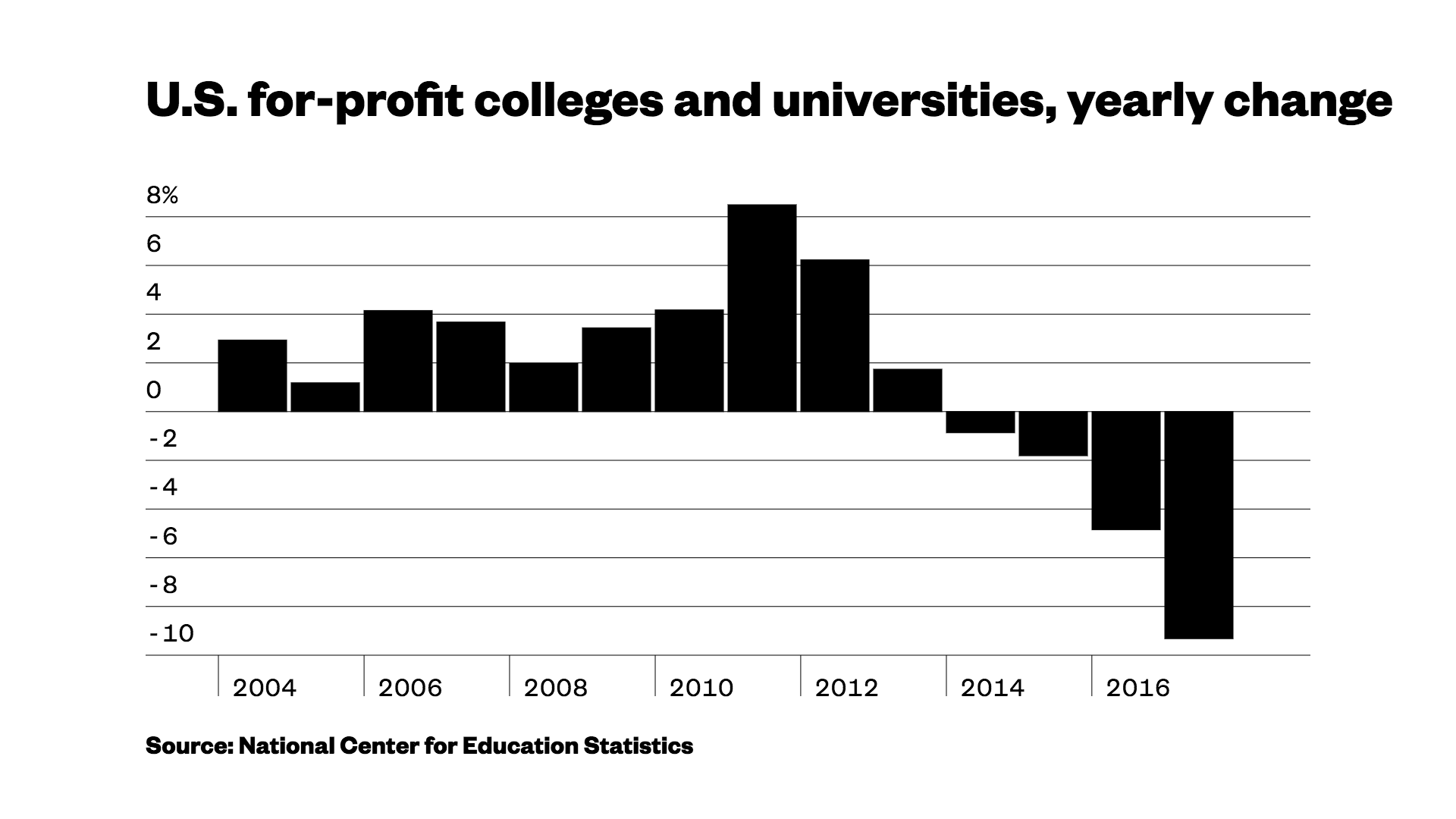

The for-profit schools that saddled millions of students with billions in debt — and left taxpayers on the hook — are closing their doors fast, thanks to a set of Obama-era federal rules.Newly released numbers from the National Center for Education Statistics show the number of all U.S. schools eligible to receive federal student aid, including Pell grants and other loans, declined to 6,606 in the most recent academic year, a 5.9 percent drop. It’s the steepest drop on record, driven to a large extent by a decline in the number of for-profit schools, which dropped 9.3 percent.Like much of the U.S. higher education system, for-profit schools are heavily reliant on federal student aid to enroll students. (For-profits typically get about 70 percent of their revenue from federal student aid programs, one academic study found.)But as student debt ballooned to more than $1.3 trillion during and after the Great Recession, regulators began to scrutinize the disproportionately bad outcomes experienced by students enrolled in for-profit schools — setting off a series of scandals and closures involving some of the biggest entities in the industry.One of the largest for-profit education companies, Corinthian Colleges, was forced to sell off most of its campuses in 2014 in the face of several investigations by state attorneys general and the U.S. Department of Education over its advertised job placement statistics. The company closed its remaining campuses in April 2015 after the Education Department fined the school $30 million for fudging its job placement rates. The closure left 16,000 students in the lurch, and taxpayers on the hook for hundreds of millions of dollars in debt that will likely go unpaid. Another major player, ITT Technical — which had some 35,000 students in 130 campuses around the country — went out of business in September 2016.Not all for-profit schools are ripoffs, and there are some good things about for-profit schools. Most for-profits offer flexible schedules that enable people with full-time jobs to attend classes on their own schedule — something traditional colleges and universities have long been unable or unwilling to provide. A 2012 study published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives found that for two-year degrees or certificate programs, for-profit schools actually have a better record on student completions than community colleges. But when it comes to four-year degrees, for-profit schools can’t compete. Study after study has found that, as a whole, they have lower graduation rates, higher tuition costs, lower graduate earnings, higher debt levels, and higher default rates than traditional colleges and universities.Nearly 20 percent of first-time undergraduate students at for-profit colleges will default on a federal loan within six years, compared to just seven percent and six percent of similar students at comparable colleges and community colleges. And even adjusting for the fact that more for-profit students tend to come from low-income backgrounds — meaning they’re likely to earn less no matter where they go to school — economists have found that for-profit students still experienced lower earnings, were less likely to be employed and were much less satisfied with their educational experience than similar students at traditional colleges.But the decline in for-profit schools was thanks to an Obama-era regulatory effort that’s still producing results. But for how long? The industry is expected to make a comeback under President Donald Trump, who himself agreed to pay roughly $25 million to settle lawsuits related to the now-defunct Trump University in January. (Trump’s election also set off a surge in the stock prices of publicly traded for-profit schools.)

But when it comes to four-year degrees, for-profit schools can’t compete. Study after study has found that, as a whole, they have lower graduation rates, higher tuition costs, lower graduate earnings, higher debt levels, and higher default rates than traditional colleges and universities.Nearly 20 percent of first-time undergraduate students at for-profit colleges will default on a federal loan within six years, compared to just seven percent and six percent of similar students at comparable colleges and community colleges. And even adjusting for the fact that more for-profit students tend to come from low-income backgrounds — meaning they’re likely to earn less no matter where they go to school — economists have found that for-profit students still experienced lower earnings, were less likely to be employed and were much less satisfied with their educational experience than similar students at traditional colleges.But the decline in for-profit schools was thanks to an Obama-era regulatory effort that’s still producing results. But for how long? The industry is expected to make a comeback under President Donald Trump, who himself agreed to pay roughly $25 million to settle lawsuits related to the now-defunct Trump University in January. (Trump’s election also set off a surge in the stock prices of publicly traded for-profit schools.) And Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has put on hold Obama-era regulations that levied financial penalties on schools that engaged in fraudulent activities, such as publishing misleading advertisements about their job placement rates. Some of those rules also made it easier for students to sue schools to have their debts wiped away, and a group of attorneys general from 19 states are suing the Education Department over DeVos’ decision to delay the implementation of those regulations. DeVos has also been appointing staffers who have ties to the for-profit industry, and some for-profit entities have suggested that now might be the time to move back into expansion mode.Speaking at an investor conference, Robert Paul, president of for-profit school DeVry, said that the regulatory focus that drove so many schools out of business has opened up a lot of potential growth opportunities for the company.“There was a significant shakeout in the industry as both large national competitors as well as local competitors, whom we compete with more so, have exited the market,” Paul said, according to transcripts published by data provider FactSet CallStreet. “Our view of the overall market conditions for the next year is much more optimistic than looking back at the previous four years.”

And Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has put on hold Obama-era regulations that levied financial penalties on schools that engaged in fraudulent activities, such as publishing misleading advertisements about their job placement rates. Some of those rules also made it easier for students to sue schools to have their debts wiped away, and a group of attorneys general from 19 states are suing the Education Department over DeVos’ decision to delay the implementation of those regulations. DeVos has also been appointing staffers who have ties to the for-profit industry, and some for-profit entities have suggested that now might be the time to move back into expansion mode.Speaking at an investor conference, Robert Paul, president of for-profit school DeVry, said that the regulatory focus that drove so many schools out of business has opened up a lot of potential growth opportunities for the company.“There was a significant shakeout in the industry as both large national competitors as well as local competitors, whom we compete with more so, have exited the market,” Paul said, according to transcripts published by data provider FactSet CallStreet. “Our view of the overall market conditions for the next year is much more optimistic than looking back at the previous four years.”

Advertisement

Advertisement