In 2013, the Supreme Court gutted the core of one of the crowning achievements of the civil rights movement: the Voting Rights Act. The 1965 bill, propelled by the historic march of protestors from Montgomery to Selma, Alabama, officially put an end to the literacy tests, poll taxes, and voting restrictions that had disenfranchised millions of minority voters for decades. And it went further than that: it also required areas of the country with a history of using these discriminatory tactics to get federal approval before making any changes to voting.

But in Shelby County v. Holder , the court allowed these areas of the country free reign over voting rules once again. For the first time since 1965, local officials could now close polls or change voting laws without the permission of the federal government. In the 5-4 ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts implied that the problems of systemic racism and voter discrimination were part of a bygone era: The Act’s rules, he wrote, were “based on decades-old data and eradicated practices.”

At the time, critics feared that local and state governments suddenly freed to pass voting laws without oversight would start to implement sweeping discriminatory policies; others warned of small, localized changes, such as closing polling places in neighborhoods where minorities vote.

Now, an exclusive analysis by VICE News has found that these worries were justified. In the years following the Shelby decision, jurisdictions once subject to federal supervision shut down, on average, almost 20 percent more polling stations per capita than jurisdictions in the rest of the country. There are now 10 percent more people per polling place in the formerly-supervised areas than in the rest of the country.

Furthermore, within 18 counties in 13 states examined at a granular level, many of the closed polls were in neighborhoods with large minority populations. This analysis is the first attempt to look nationally at poll closures since the heart of the Voting Rights Act was removed.

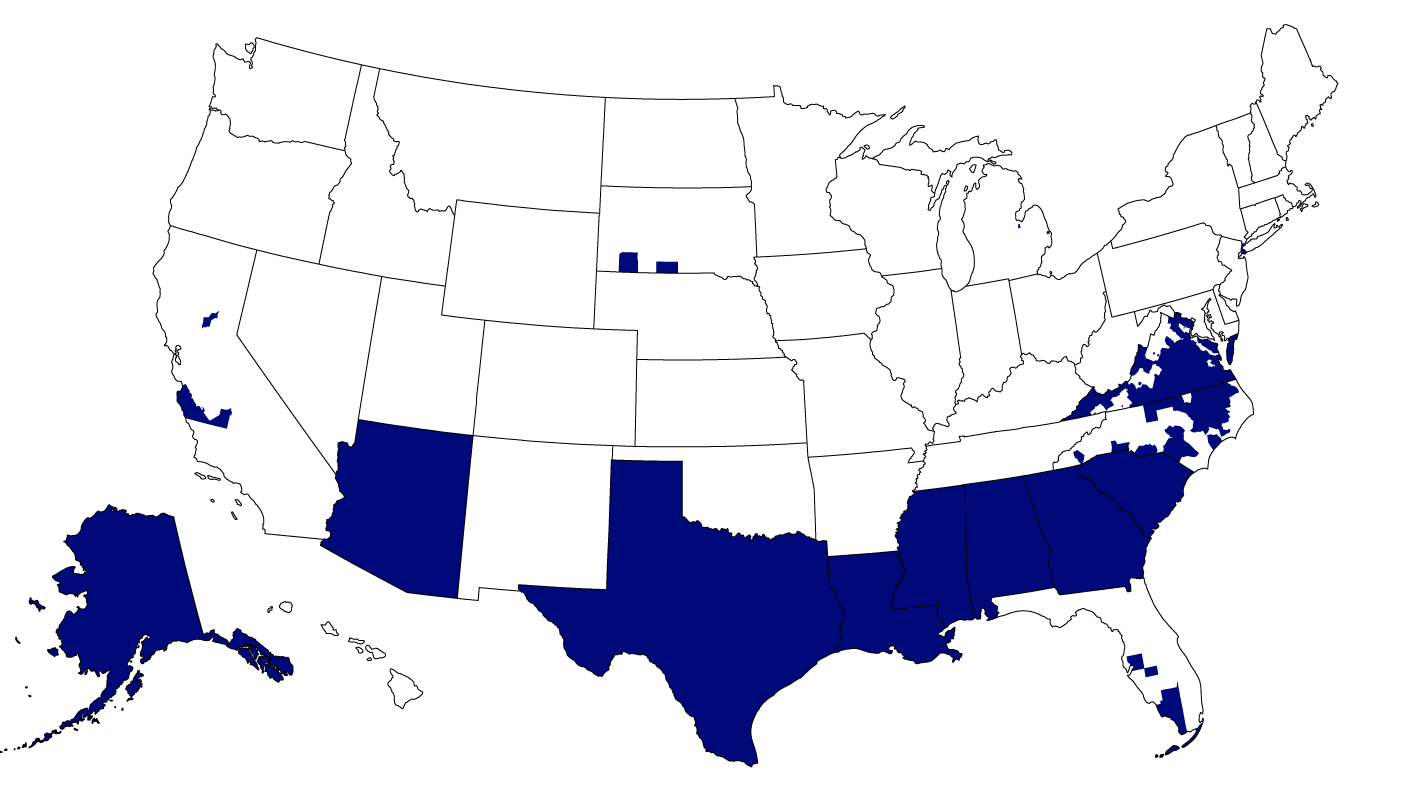

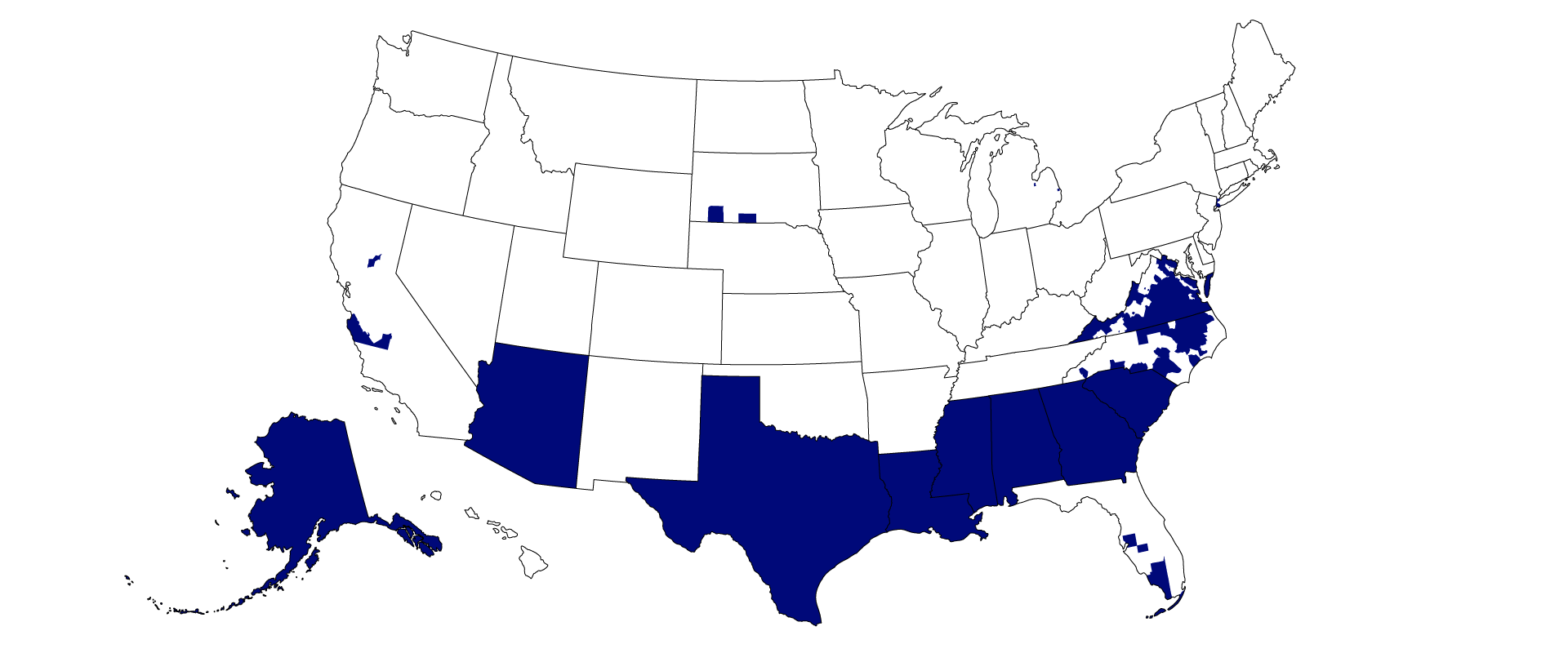

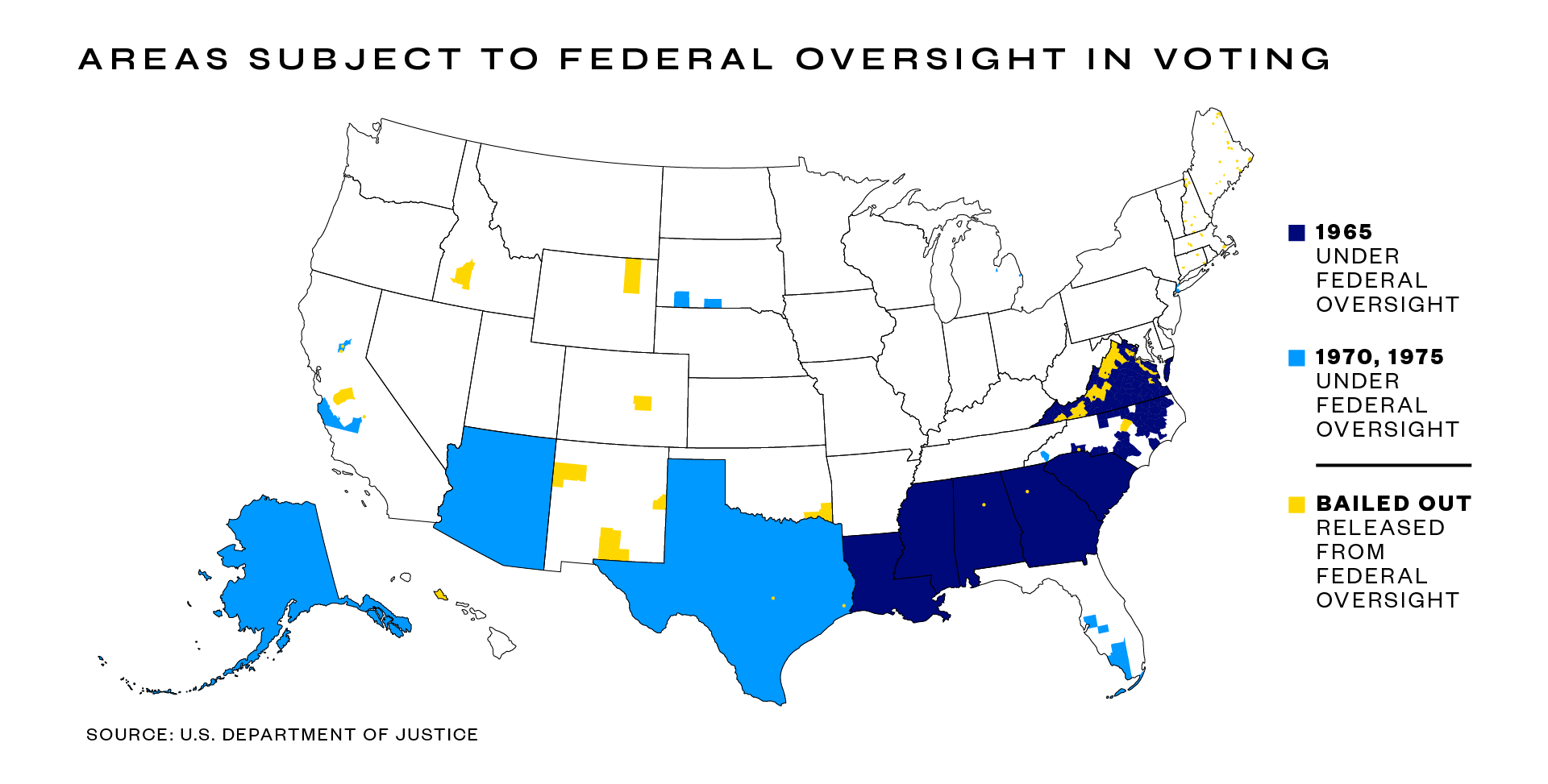

The jurisdictions required to submit voting changes to the Department of Justice or the federal district court in D.C. were selected based on a formula that looked at whether they had ever used any tests or devices for race-based discrimination. The formula also took into account whether less than 50 percent of eligible voters in these areas — states, counties, and towns, overwhelmingly in the South — were registered by November 1964.

In 1970 and 1975 the Supreme Court expanded the Voting Rights Act’s protection to include voting discrimination against people of “language minority groups.” This added Arizona, Texas, and Alaska in their entirety, as well as parts of California, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and South Dakota.

This all ended when the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby that the formula used to determine those jurisdictions no longer reflected current voting conditions. The decision allowed 846 jurisdictions to close, move or change the availability of local polling places without federal oversight — a decision often left to a single election official.

With the expansion of early voting and voting by mail, there are valid reasons for counties to close or consolidate polling places that have nothing to do with discrimination. Across the country, more than 2,000 polling places closed between the 2012 and 2016 general elections.

But VICE News found that for every 10 polling places that closed in the rest of the country, 13 closed within the jurisdictions once under oversight. Policies that introduce barriers to voting — like Texas’ strict voter ID requirements and North Carolina’s elimination of same-day registration and limits on early voting — have been widely criticized for discouraging minority voters, who disproportionately vote Democratic. The vast majority of the jurisdictions once under federal supervision are in states with GOP leadership.

“I think what we’re seeing [are] modern-day form[s] of voter suppression that are still occurring, and while they are not as egregious or as overt as literacy tests or poll taxes, they are nevertheless decreasing participation,” said Rep. Terri Sewell, an Alabama Democrat.

The people most burdened by changes that make it more difficult to vote are poorer and more likely to be people of color. Poll closures can increase travel time and the length of lines. Low-income voters — who may not own cars and have less time to devote to registering or standing in line — may be unable to participate if the barriers are too difficult.

“It’s very hard to dispel this myth that voting is supposed to be burdensome,” said Leah Aden, a lawyer at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “There’s this expectation that if you don’t jump over hurdles, you’re lazy or you don’t want to participate — and I think that’s rooted in racism and classism.”

Voting on an Arizona reservation: “We are different.”

The #29 bus runs every 30 minutes from the station stop outside of the Casino of the Sun, the smaller of the two casinos located on the Pascua Yaqui Native American reservation. A small sign taped to the station bench reads “CAST YOUR BALLOT EARLY!”

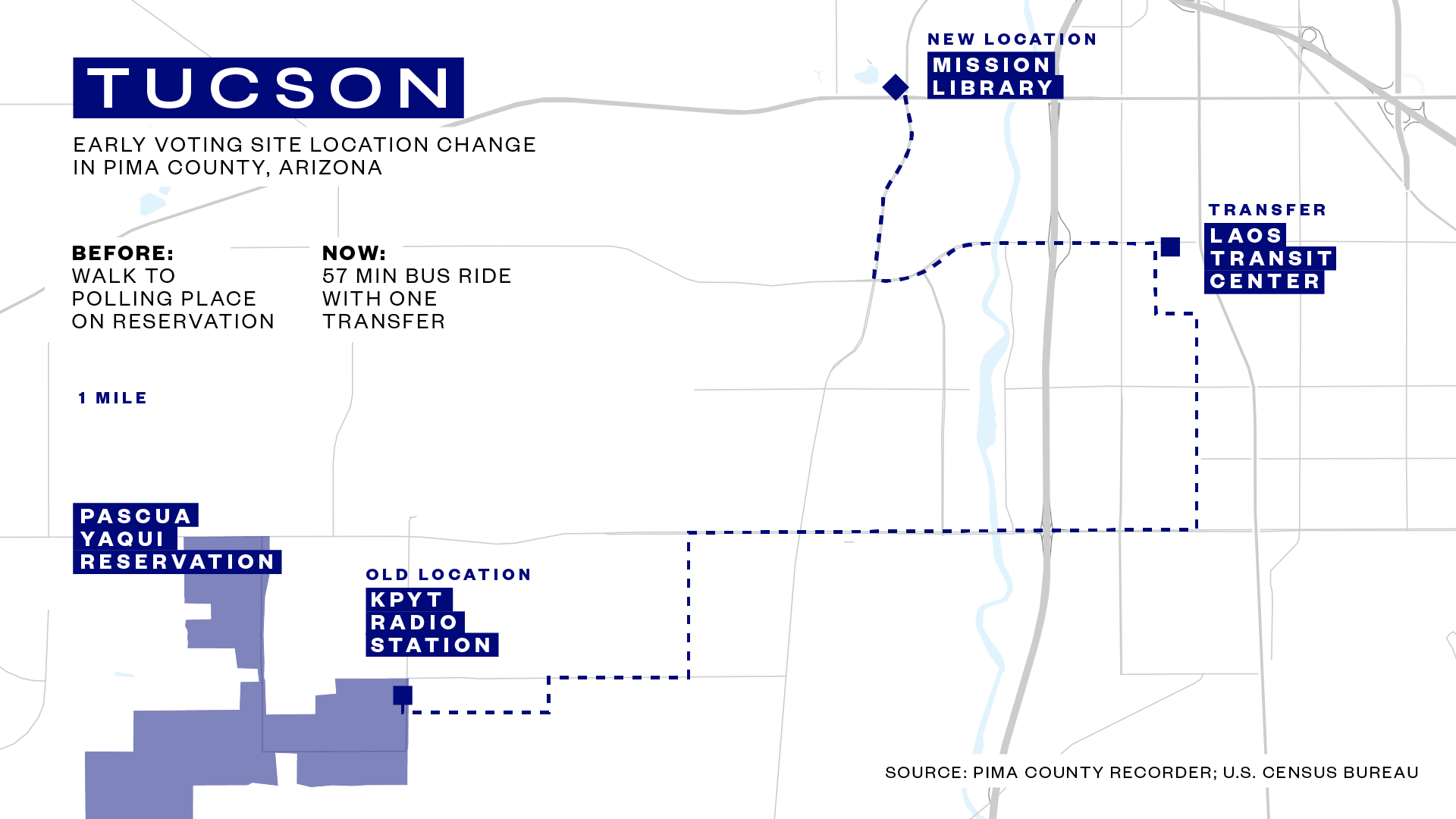

Rebekah T. Ello-Lewis, an assistant for voter outreach, didn’t expect anyone to travel off the reservation to vote early, but she wanted to know what the eight-mile journey on public transportation entailed. The 29-year-old Pascua Yaqui mother catches the first of two buses around 11 a.m. and rides for half an hour, winding through flat desert roads. She transfers at the Laos Transit Center and pays the fare again, riding for another 30 minutes before reaching the Mission Library. It takes her less than two minutes to cast her ballot; the one-way trip took about an hour.

Since 2010, the Pascua Yaqui had hosted an early voting site on the reservation, a three-square-mile plot of land about 15 miles outside of downtown Tucson, Arizona. But about a month before Arizona’s August primary election, the Pima County recorder’s office informed tribal leaders that they were moving one of the city’s 11 early voting locations off the reservation.

F. Ann Rodriguez, the Pima County recorder, cited low turnout figures as the reason behind her decision to close the polling station. She said only 44 voters cast a ballot on the reservation during the five days of early voting in 2016, compared with nearly 10,000 voters in the precinct who cast a ballot by mail (these figures include both tribal and nontribal voters).

“They [the Pascua Yaqui] just don't like to go to the early voting site. They like to vote by mail, or they're traditionalists,” Rodriguez said, implying that tribal members prefer to vote on Election Day. Tribal leaders, however, argue that their recent efforts to increase voter turnout were not taken into consideration. In March, they launched “Yaqui Vote,” holding more than 40 voter outreach and registration events this year.

“We've been working so hard, and then for them to tell us this — for her to say it’s not enough — it was kind of like they just knocked everything out from underneath us,” said Letticia Baltazar, the tribe’s director of voter outreach.

The Pascua Yaqui still have a polling place available on Election Day, but tribal leaders feel the removal of the early voting site wasn’t done with a commensurate effort to encourage alternate methods of voting.

“I know Pima County is really counting on mail-in ballots, but then they have to put some effort into educating people about how to do that,” said Herminia Frias, a Pascua Yaqui council member. Frias said many Yaqui voters either don’t know they can vote by mail or are unfamiliar with the process of requesting a mail ballot.

Between the 2012 and 2016 general elections, Pima County closed 15 percent of its Election Day polling locations, a drop that county officials largely attribute to the rise in early voting. About 70 percent of Pima County voters now cast a ballot early, either by mail or at an early voting site.

Robert Valencia, the chairman of the tribe, said the decision by the recorder’s office felt reminiscent of when Native American voting rights were limited — they weren’t granted full U.S. citizenship until 1924, and in Arizona Native Americans weren’t able to vote until 1948.

“The movement from the recorder's office has been vote by mail. And that's worked for Tucson in general, and so I think they see the reservation as no different,” said Frias. “But it is different. We are different.”

The data

In 34 states, VICE News collected data directly from a state authority like the secretary of state or elections division. Four states — Colorado, Oregon, Washington, and Utah — were excluded from our analysis because they are either entirely or predominantly vote-by-mail and have few physical polling places. We also excluded counties that utilize a vote center model, in which voters can cast ballots at any location in the county.

In the 12 states where a state authority was unable or did not provide data, we relied on the Election Administration and Voting Survey. Polling place data can be inaccurate, in part because each county is responsible for maintaining its own location data and forwarding it to the state authority. In many cases, data from the federal Election Administration and Voting Survey did not match the information from state or local authorities.

To further strengthen our data, we contacted individual county or state authorities with over 50 polling place closures, or ones that had changed their number of polling places by more than 50 percent, in case there had been a recording error. The data covers 94,790 polling places in 2012 and 92,740 in 2016, or about 90 percent of electoral jurisdictions — and accounts for 233 million people in 2016, or more than 90 percent of the voting age population.

About a third of all counties that used to be subject to the Voting Rights Act reduced their per capita number of polling places from 2012 to 2016, compared to only a fifth of the rest of the jurisdictions. Rapidly growing states like Arizona and Georgia closed around 150 polling places each, while a few states, including Virginia and South Carolina, opened additional polling places.

But on balance, the jurisdictions freed from having to seek approval for closures shut down, on average, about 2.6 percent of their polling places from 2012 to 2016, while counties in the rest of the country closed 2.0 percent.

Alternative methods of voting, either early or by mail, can help to offset closures by providing other, sometimes more convenient, options for voters whose polling places have closed. Since 2012, 26 states have enacted laws to expand access to voting — but only four of those states were ones formerly subject to oversight, according to an annual survey of new voting laws by the Brennan Center.

Furthermore, many more people vote in person within the counties previously subject to oversight, according to data gathered by MIT on 1,429 counties. Using their data, we found that voters cast about 77 percent of their ballots in person on Election Day in the counties formerly subject to oversight, compared to 61 percent outside of that area.

VICE News conducted a granular analysis of 18 counties, examining the travel times between each Census block group and the nearest polling place, correcting for differences in car ownership. Within some counties, a disproportionate number of polls closed in neighborhoods with large minority populations.

In 11 jurisdictions, polling place closures increased the travel times for majority nonwhite blocks more than they affected majority white areas. The average travel time for mostly white neighborhoods was 21 seconds longer after polling place closures, while in minority neighborhoods it increased by 46 seconds. In areas formerly subject to oversight, average travel times increased by more than a minute for majority nonwhite neighborhoods.

In 17 of the 18 counties, at least one neighborhood had an increase in average travel time of more than 5 minutes. (Neighborhoods averaged around 1,000 people.) These block groups were about two-thirds nonwhite.

And for about a quarter of people in these neighborhoods without a car, the average travel time to the nearest polling place was over an hour. Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a professor of election and government law at the University of Chicago, said that the polling place closures we analyzed could have a “clear disparate impact” on minority voters.

Some of the most egregious examples of counties closing a significant percentage of their polls are in Arizona. Phoenix-area Maricopa County initially slashed its polling places by 70 percent before the state’s 2016 primary election, spurring a DOJ investigation. (They later reversed course before the general election, restoring most of the lost polling places.) Mohave and Coconino counties trimmed dozens of polling places each, citing concerns about violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act and a lack of funding.

In Pima County, the area around Tucson, the combination of poll closures and movement increased the travel time for majority nonwhite areas (29 seconds) by about 50 percent more than it increased travel times for white areas (19 seconds).

Backlash in Georgia: “What is the price of our democracy?”

In August, lawyers from the ACLU of Georgia were alerted to a proposal to close seven of nine polling places in the rural, predominantly black Randolph County. The county’s board of elections said the advice to cut almost 80 percent of poll locations came from an outside consultant, Michael Malone, who argued that the sites were not compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (though no reports or documents supported this assertion.)

The ACLU of Georgia threatened legal action, and after two heated public meetings, the board voted 2-0 against the closures. Randolph County also fired Malone. “We heard about Randolph County and we were able to stop them [from closing the polls], but there are 159 counties in Georgia,” said Sean Young, the legal director of the ACLU of Georgia.

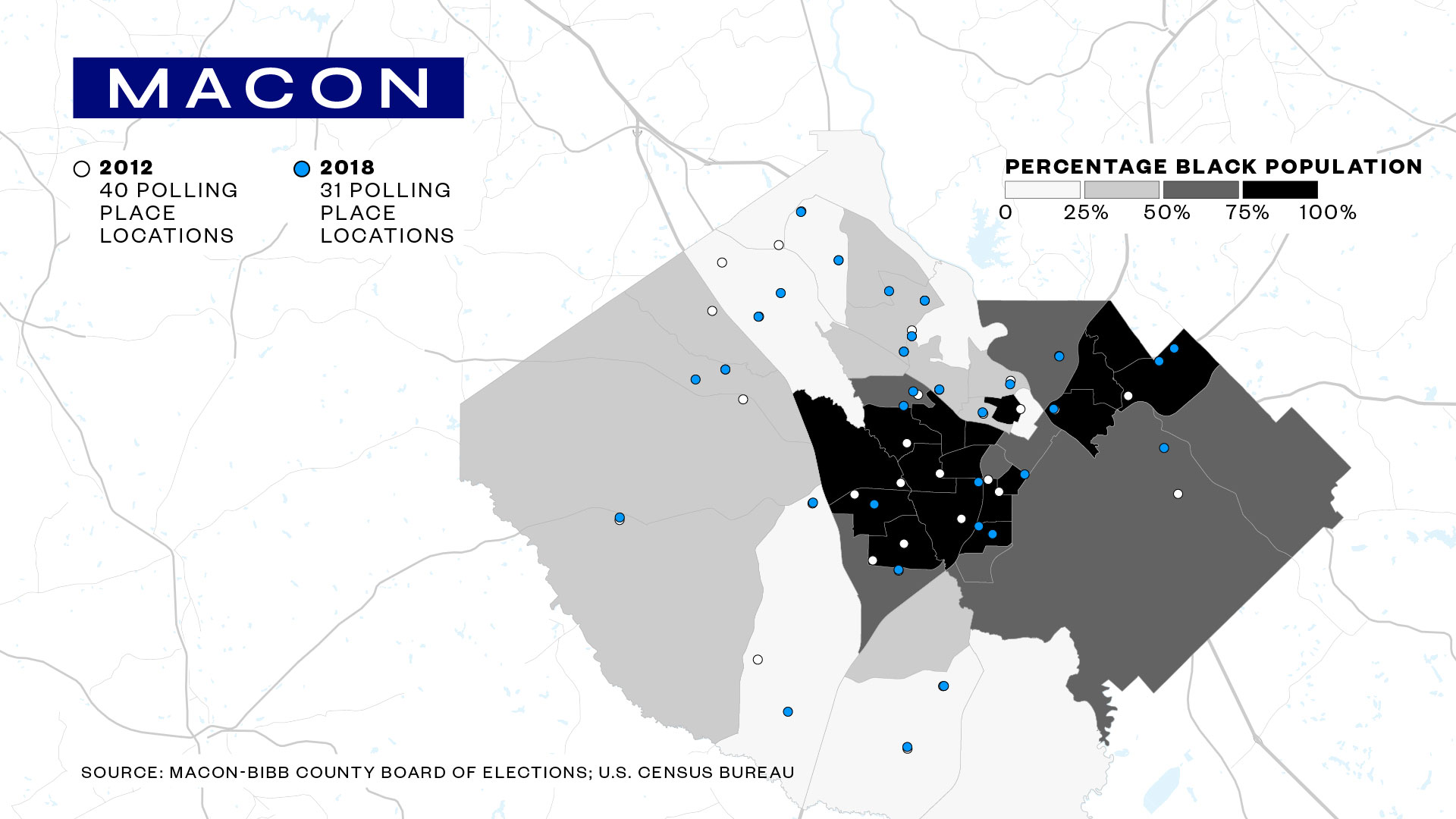

Three years earlier, in nearby Macon-Bibb County, civil rights organizations weren’t as successful. In 2012, Bibb County had 40 polling places. Two years later, the county merged with the city of Macon, and in the process, “all departments were asked to cut their budgets,” said elections officer Tom Gillon. In 2015, the newly formed Macon-Bibb County Board of Elections proposed reducing the number of polling places to 26, stating that the closures would save them around $40,000 annually.

The local NAACP quickly intervened, and an advisory panel was formed to reconsider the closures. “All of the places where they were proposing to close polls were within neighborhoods of low-income or majority black people,” said Gwen Westbrooks, the president of the Macon-Bibb NAACP chapter.

The board ultimately decided to close eight locations that year, and another the following. Macon-Bibb County now has 31 polling places for nearly 100,000 registered voters, about 30 percent more voters per polling place than the national average.

Johnisha Carswell liked voting at Agnes Barden Elementary School, one of the eight locations that closed in 2015. It was less than a mile from her home, and she could walk there with her three children. “It was easy because we was taking the kids to school and we could just stop on by and vote,” she said from her front door, watching her husband fix a flat tire.

The Carswells now vote at a church about two miles up the road, but it’s not easily accessible by public transportation. The family shares one car, which her husband Marcus Carswell usually takes to drive to work. In 2016, Johnisha got a ride from her mom to go and vote.

“I think our job is just mainly to make sure you're registered and come vote. And we can't really get into, ‘OK, you don't have a car,’” said Jeanetta Watson, the elections supervisor. Watson makes recommendations to the five-person Board of Elections, who ultimately decide when to close or consolidate polls. “We do take that [public transportation] into consideration, but I don't think there are bus lines near a lot of our polling locations.”

Rolston Mondaizie, the pastor at the Central Church of Christ, remembers past Election Days fondly. “We felt privileged to host the voting precinct here, and we felt it was our obligation to the community,” said Mondaizie. “And for a number of years — probably 10 years — the community came in and voted here.” He said a few people still show up at the church each Election Day to try to vote, and that he directs them to the new location.

The polling place moved less than a mile away, to a medical complex with “more room and space,” said Watson. She said they withdrew voting at the Central Church of Christ because they often had a hard time reaching Mondaizie and getting the church open on Election Day. (Mondaizie disputes this, and said he attended the board hearings and asked to keep the poll location open at his church.)

Macon’s poll closures, like in many counties across Georgia, were done in an apparent effort to save money. Watson said the county isn’t saving the projected $44,000 per year, but she estimated it was close, “maybe 20 or 30 thousand,” depending on whether it’s a presidential or non-presidential election year.

“Government employees always want to save money and do less work, but that’s not an adequate justification for infringing on constitutional rights,” said Young. “What is the price of our democracy?”

An outdated formula

The formula that determined which jurisdictions would be subject to supervision under the Voting Rights Act was based on decades-old information on voter registration and suppression measures, although it included a “bailout” provision for jurisdictions that could show they hadn’t discriminated in voting for 10 years.

Despite the possibility of a “bailout,” there were many constitutional challenges by local politicians who believed their jurisdictions no longer needed federal oversight. In 2010, officials in Shelby County, Alabama, sued the U.S. Attorney General. They argued that when Congress reauthorized the Voting Rights Act in 2006, it did not account for current voting conditions.

The Supreme Court agreed. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “The formula captures States by reference to literacy tests and low voter registration and turnout in the 1960s and early 1970s. But such tests have been banned nationwide for over 40 years.”

Sewell believed that the Voting Rights Act didn’t cover enough states. “I would love for all 50 states to be covered under the Voting Rights Act,” said Sewell, who sponsored legislation to restore the full protections of the Voting Rights Act with an updated formula that would cover a few additional Southern states. It didn’t make it out of committee.

VICE News’ analysis revealed that jurisdictions that weren’t subject to oversight also reduced the number of polling places overall. Counties in Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia closed an additional 329 polling places, for a closure rate about as high as the previously supervised states. And the trend persists outside of the South: Ohio and Indiana each closed over 300 polling places.

A Florida county as a bellwether: “Why would we make it any easier?”

Plagued by 45-minute lines at the polls in 2012, Manatee County elected a new supervisor of elections, Mike Bennett. Bennett had previously served in the Florida legislature, but term limits forced him out. While there, he made controversial comments about voting. “Why would we make it any easier? I want 'em to fight for it,” he said in a 2011 speech. “I want the people of the state of Florida to want to vote as bad as that person in Africa who’s willing to walk 200 miles.”

Two years after his election, Bennett proposed a 30 percent reduction in the number of polling places in Manatee County, which was not subject to federal preclearance. The proposed closures were primarily in heavily Latino and black areas of the county. Eleven speakers at the county commissioners’ meeting opposed Bennett’s plan; he was the only person to speak in favor of it. It passed over the objections of the lone Democratic county commissioner.

“Nobody [went] there,” Bennett said of the closed polling places. Asked whether he considered the racial or demographic makeup of the areas surrounding closed polling places, Bennett simply answered “No.” Money from the closures went into opening early voting locations and an aggressive vote-by-mail campaign. Bennett said that early voting tallies doubled as a result.

But research from three University of Florida academics shows that in-person voting declined precipitously as a result of the closures. Their 2016 paper showed that while white voters disadvantaged by the closures turned to other ways to cast their ballot, black and Latino election turnout in the county dropped by 3 and 5 percent, respectively, for voters whose polling place had changed.

In theory, voters who have difficulty traveling to a polling place can cast a vote through the mail. In practice, many voters prefer to cast a ballot in person, even if it’s less convenient. “For old-fashioned folks, man, there’s something about going to the polls. Even for me — I’m 51 and I’ve got a 14-year-old daughter — I take my daughter to the polls with me every time so she can stand with me,” said Rodney Jones, the president of the Manatee County chapter of the NAACP.

Jones’ own old polling place, a church within a five-minute walk, was relocated to a civic center across the railroad tracks. It’s at least a 30-minute trip on foot, and impossible to get to without a car for older voters or people with disabilities, Jones said. “We still have transportation impediments,” Jones said about people in his community, which is predominantly black.

Even when a voter tries to shift to vote-by-mail, it may not be an easy transition. About 10 percent of Manatee’s population speaks Spanish at home. Bennett, like many other local officials, has resisted printing ballots in Spanish, but civil rights organizations suing the state recently won an emergency injunction that will force 32 counties in Florida to provide ballots in Spanish during the midterm elections.

A danger to democracy

In her dissent to the Shelby decision, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said removing federal oversight from the Voting Rights Act was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

In addition to polling place closures, reports have documented other policies that appear intended to reduce voter participation such as voter registration purges, laws requiring specific forms of identification, and reductions in access to early voting.

Taken together, experts believe that the overall impact is to reduce voter participation through myriad small inconveniences. “Without question, these kinds of mechanisms send a message to voters of color in particular that we are less American than other Americans. It’s dangerous to democracy,” said Catherine Lhamon, the chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, a bipartisan federal watchdog agency.

Several previous attempts to introduce new legislation to replace the Voting Rights Act have failed, ranging from Wisconsin GOP Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner’s bill to Democratic Rep. Sewell’s proposal.

“Many of the excuses given to me to oppose my bill have been a pretext for the fact that the people who would benefit — if we decreased barriers to voting — would be folks of color,” said Sewell. “And they may not be voting for Republicans; they may be voting for Democrats.”

In a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report on minority voting rights released in September, the agency unanimously called on Congress to amend and expand the protections of the Voting Rights Act once again.

The Act “has been called among the most important congressional enactments of any time — and not just civil rights,” said Debo Adegbile, a commissioner. “Congress has the power to do more in this regard, and the country will be better for it.”