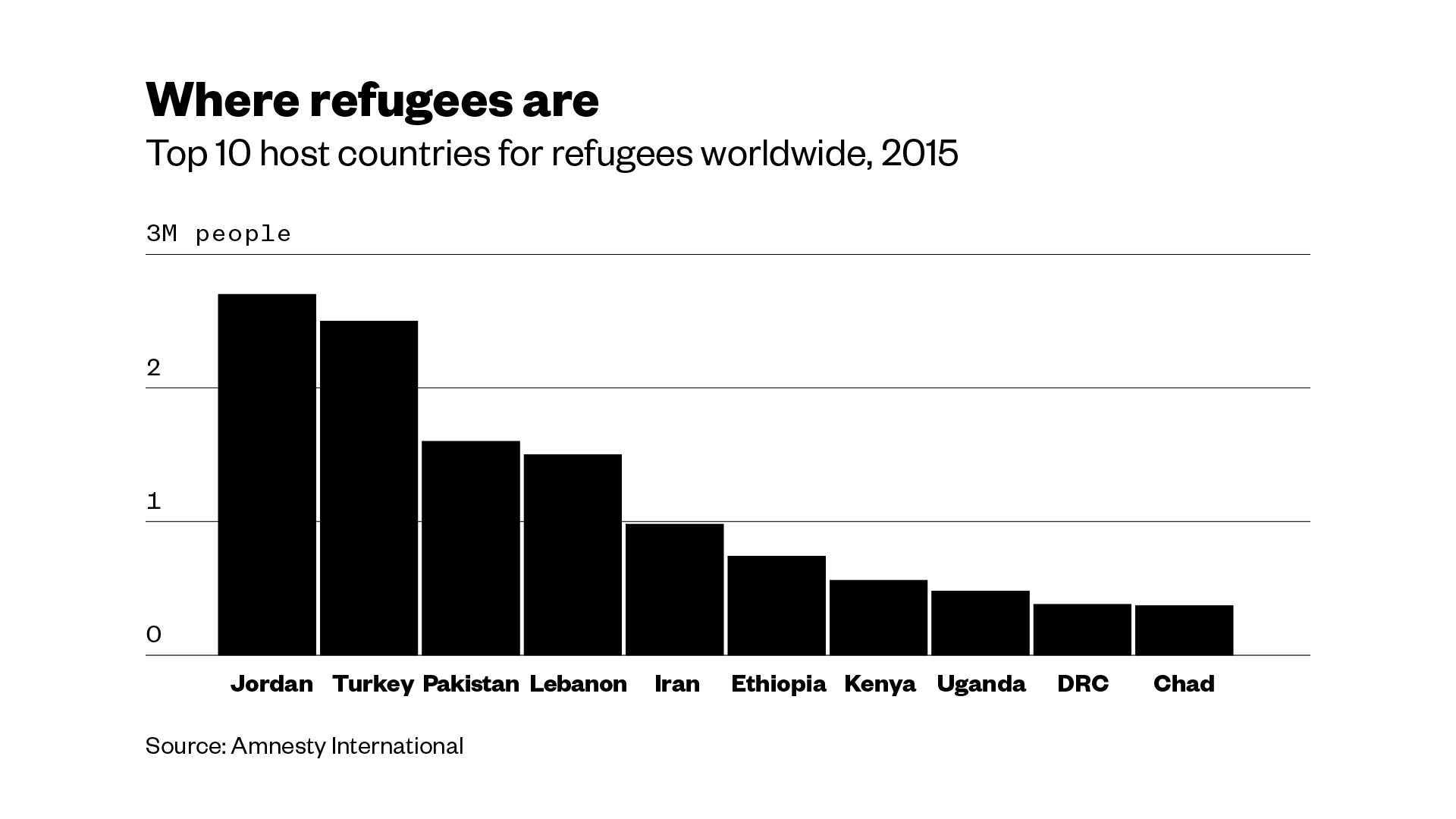

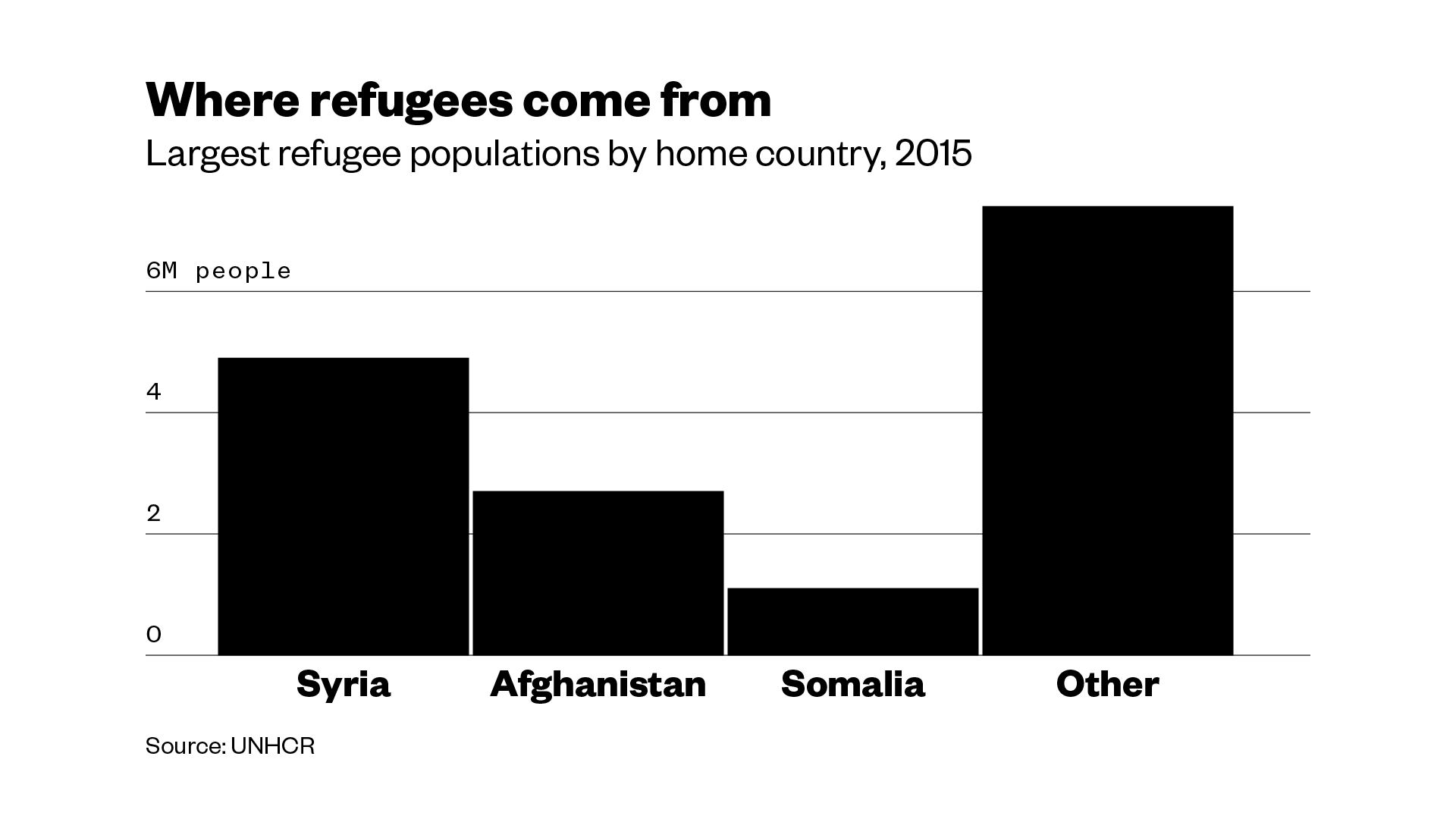

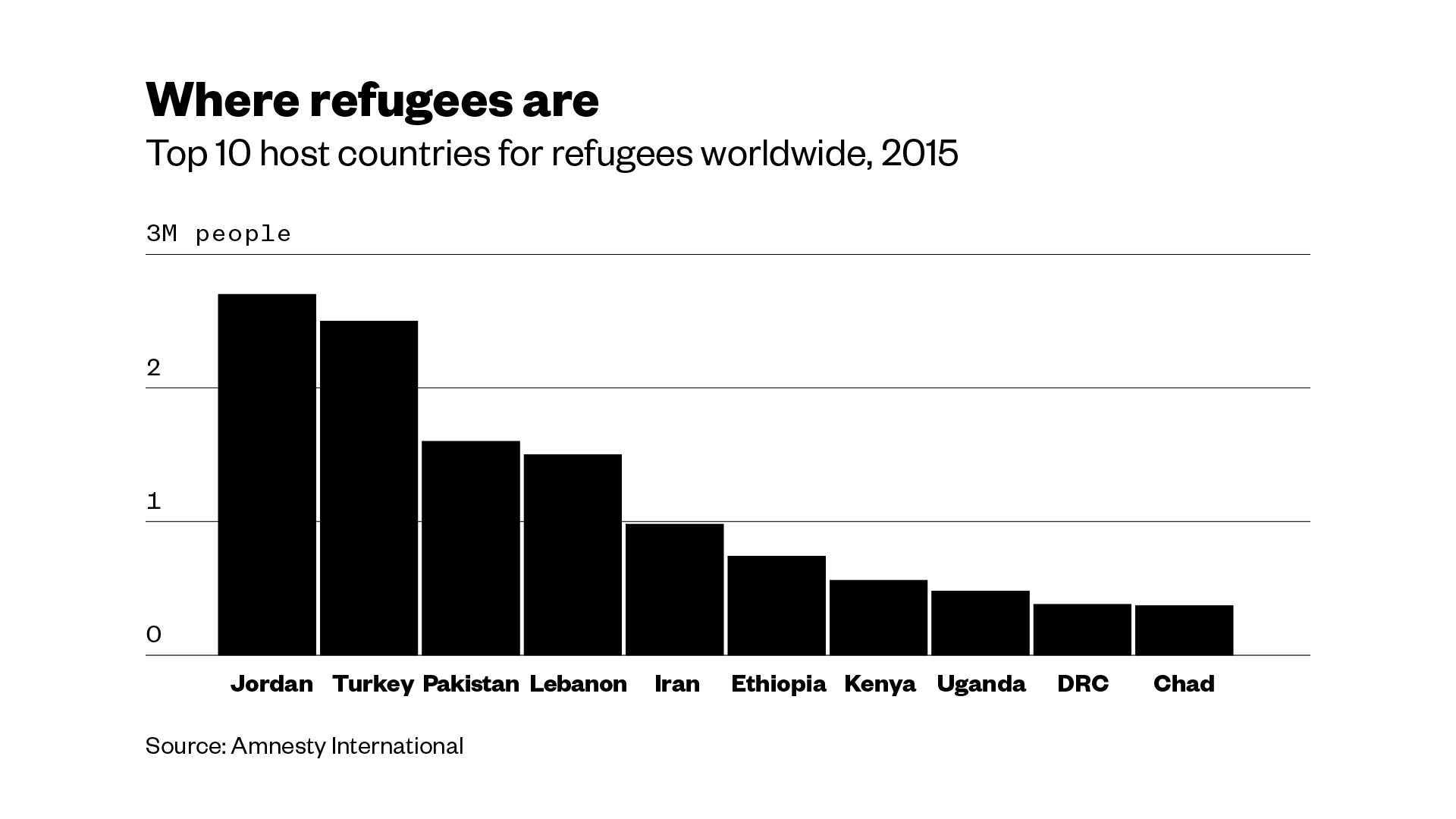

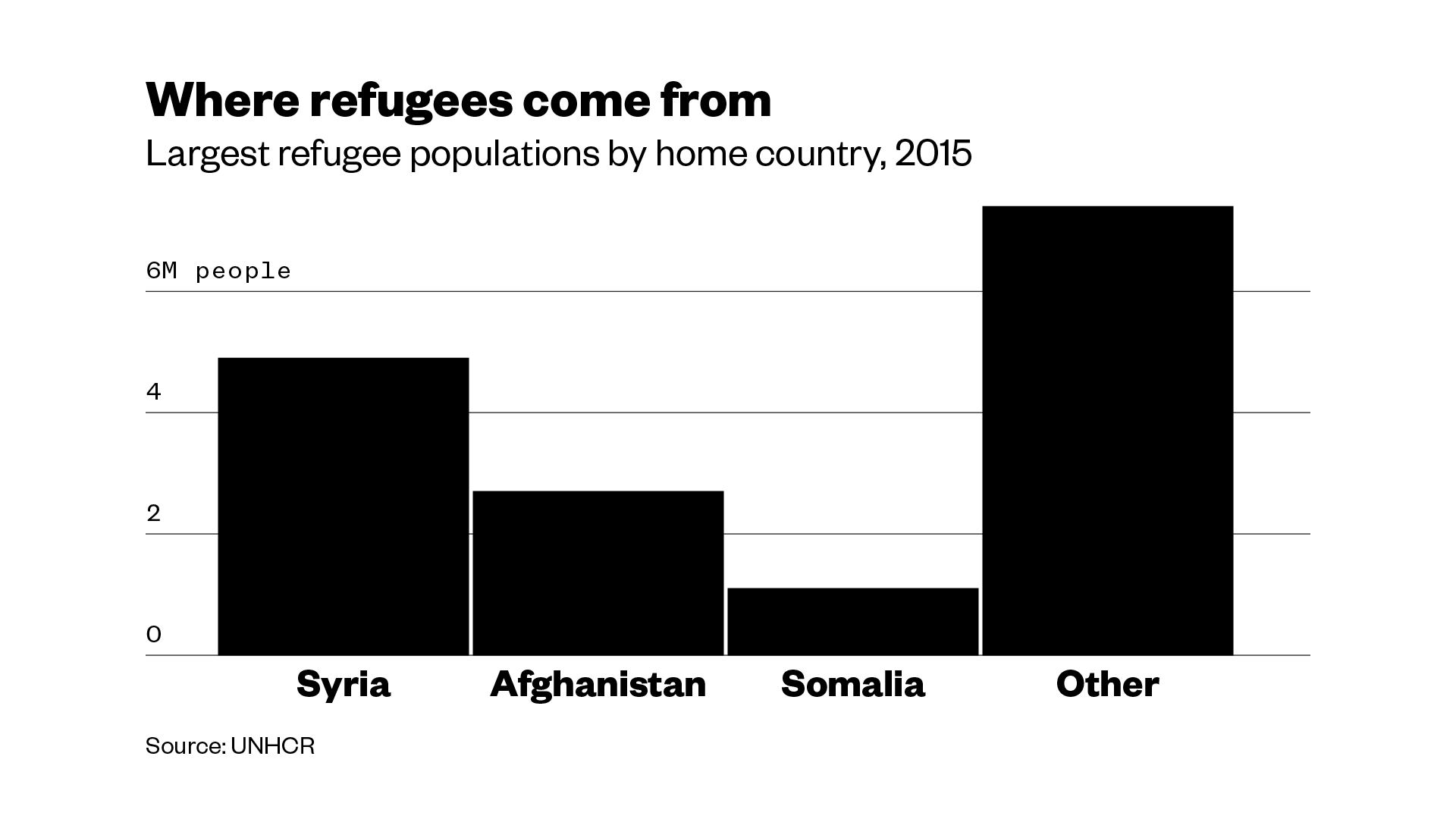

Updated on January 28 to reflect the latest information on Donald Trump’s executive order.President Trump just derailed the United States refugee resettlement program amid the greatest refugee crisis since World War II and just days after the United Nations called for greater assistance in Syria specifically.The move crushes the hope of reunification for refugees already here but whose family members remain abroad and throws into disarray the agencies that for years have quietly worked to help refugees settle into their new communities. Just as significantly, aid experts and humanitarians fear, it sends a stark message to other countries that the U.S. will no longer share the burden of the world’s most pressing humanitarian cause, and it could further embolden terror organizations that have found new inspiration and recruitment fodder in Trump’s rhetoric and actions.Chris George, director of the Integrated Refugee Resettlement Program in New Haven, Connecticut, said Trump’s decision will have a stark and immediate impact on the ground. “It means more refugees out of desperation placing their children in so-called boats that will sink in the Mediterranean,” he said, “more refugees languishing and sweating it out in refugee camps.”Trump’s executive order institutes at minimum a four-month suspension of all refugee admissions into the United States, indefinitely bans all Syrian refugees, and blocks entrance to anyone (including U.S. green card holders) from Syria, Somalia, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Sudan, and Yemen for a minimum of 90 days while the government considers greater visa restrictions.Although the U.S. has long been a leader in refugee resettlement, it had just begun to accept refugees from these countries in numbers resettlement workers say are necessary to cope with the current crisis. The American response was initially bogged down, in part, by political controversy surrounding Syrian refugees after the terror attacks in Paris in November 2015.Trump’s executive order will bring new challenges and added scrutiny to Muslim refugees, who will now fall behind Christians and other minority faiths on the list of U.S. resettlement priorities when the program resumes. An overwhelming share of the world’s refugee population comes from Muslim-majority countries.Just three countries — two of which are specified in Trump’s 30-day ban — account for 54 percent of all refugees worldwide. The United Nation’s refugee agency forecasts that roughly 1.2 million of the 16.1 million refugees under the organization’s mandate will need to be resettled in 2017, half of whom are children. Yet the organization expects to submit only 170,000 refugees for resettlement globally during that time. Some 110,000 of those were scheduled to arrive in the U.S before Trump’s order more than halved that count to 50,000. The remaining 15.9 million refugees will have to seek asylum in camps and countries closer to home where they often face little opportunity for education or employment.“The U.S. role in resettlement of refugees is one other countries have historically emulated,” said Robert Carey, the outgoing director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, during a roundtable event on refugee response in December. “So it has implications not only for our own country but for the global response to refugees.”As a candidate, Trump was a constant and forceful critic of the historically bipartisan U.S. refugee resettlement program and repeatedly cast aspersions on Syrian refugees, whom he described as “pouring” into the country and likened to snakes and a Trojan horse. He has accused these same refugees of carrying Islamic State sympathies and he has called for “extreme vetting” of all asylum-seekers from countries “compromised by terrorism.” The current, exhaustive screening process requires asylum-seekers to undergo a series of background checks that normally take 18 to 24 months and involve running an applicant’s fingerprints against multiple databases from the United Nations and at least five American agencies. The new order calls to review and expand on this screening.This segment first appeared on VICE News Tonight on HBO on Monday, Jan. 23, 2017.A favorite refrain among his supporters on the campaign trail, Trump’s attacks on refugees tapped into much of the country’s rising fear of terrorism while locating a convenient straw man in his rhetorical battle against ISIS. But until recently, refugee resettlement hardly ever broached mainstream American consciousness, and when it did it was rarely under a cloud of controversy.“When I first started as a volunteer, I never imagined it would be controversial to try to help refugees,” said Angie Plummer, the director of the Columbus-based resettlement organization CRISOhio who has been resettling refugees for the better part of two decades.Since Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, the effort has resettled more than 2 million people from at least 70 countries. In the program’s first year, the U.S. took in a record 207,000 people amid crises in Cuba and Southeast Asia. In a statement released the following year, Reagan said, “More than any other country, our strength comes from our own immigrant heritage and our capacity to welcome those from other lands.”But the U.S. has played a diminished role in the current global refugee crisis, especially when it comes to Syrians, a group that comprises nearly a quarter of the world’s 21 million refugees. Neighboring countries, including Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon, have borne the brunt of recent, record-breaking mass displacement in Syria, where nearly 5 million people have fled since the start of the country’s civil war, now approaching its sixth year.Just 12,000 Syrians were resettled in the U.S. in fiscal year 2016, less than an eighth of the 85,000 refugees allowed into the country. But that marked a considerable uptick compared to years prior — the U.S. resettled fewer than 2,000 Syrian refugees between 2012 and 2015. Canada, by contrast, has resettled 30,000 Syrian refugees since 2015.And the world’s wealthiest nations’ response to the greater global refugee crisis is hardly much different. A recent report by Amnesty International found that just 10 countries take in half the world’s refugees. For its part, Germany has taken in more than 1 million refugees, a move that Donald Trump recently called a “catastrophic mistake.”

The United Nation’s refugee agency forecasts that roughly 1.2 million of the 16.1 million refugees under the organization’s mandate will need to be resettled in 2017, half of whom are children. Yet the organization expects to submit only 170,000 refugees for resettlement globally during that time. Some 110,000 of those were scheduled to arrive in the U.S before Trump’s order more than halved that count to 50,000. The remaining 15.9 million refugees will have to seek asylum in camps and countries closer to home where they often face little opportunity for education or employment.“The U.S. role in resettlement of refugees is one other countries have historically emulated,” said Robert Carey, the outgoing director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, during a roundtable event on refugee response in December. “So it has implications not only for our own country but for the global response to refugees.”As a candidate, Trump was a constant and forceful critic of the historically bipartisan U.S. refugee resettlement program and repeatedly cast aspersions on Syrian refugees, whom he described as “pouring” into the country and likened to snakes and a Trojan horse. He has accused these same refugees of carrying Islamic State sympathies and he has called for “extreme vetting” of all asylum-seekers from countries “compromised by terrorism.” The current, exhaustive screening process requires asylum-seekers to undergo a series of background checks that normally take 18 to 24 months and involve running an applicant’s fingerprints against multiple databases from the United Nations and at least five American agencies. The new order calls to review and expand on this screening.This segment first appeared on VICE News Tonight on HBO on Monday, Jan. 23, 2017.A favorite refrain among his supporters on the campaign trail, Trump’s attacks on refugees tapped into much of the country’s rising fear of terrorism while locating a convenient straw man in his rhetorical battle against ISIS. But until recently, refugee resettlement hardly ever broached mainstream American consciousness, and when it did it was rarely under a cloud of controversy.“When I first started as a volunteer, I never imagined it would be controversial to try to help refugees,” said Angie Plummer, the director of the Columbus-based resettlement organization CRISOhio who has been resettling refugees for the better part of two decades.Since Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, the effort has resettled more than 2 million people from at least 70 countries. In the program’s first year, the U.S. took in a record 207,000 people amid crises in Cuba and Southeast Asia. In a statement released the following year, Reagan said, “More than any other country, our strength comes from our own immigrant heritage and our capacity to welcome those from other lands.”But the U.S. has played a diminished role in the current global refugee crisis, especially when it comes to Syrians, a group that comprises nearly a quarter of the world’s 21 million refugees. Neighboring countries, including Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon, have borne the brunt of recent, record-breaking mass displacement in Syria, where nearly 5 million people have fled since the start of the country’s civil war, now approaching its sixth year.Just 12,000 Syrians were resettled in the U.S. in fiscal year 2016, less than an eighth of the 85,000 refugees allowed into the country. But that marked a considerable uptick compared to years prior — the U.S. resettled fewer than 2,000 Syrian refugees between 2012 and 2015. Canada, by contrast, has resettled 30,000 Syrian refugees since 2015.And the world’s wealthiest nations’ response to the greater global refugee crisis is hardly much different. A recent report by Amnesty International found that just 10 countries take in half the world’s refugees. For its part, Germany has taken in more than 1 million refugees, a move that Donald Trump recently called a “catastrophic mistake.” After a slow start, President Obama pushed the 2017 goal to 110,000 total refugees in his final remarks to the United Nations in September, a nearly 30 percent increase from the year before. Hillary Clinton that same day said she would take in 65,000 more Syrian refugees if she were to become president — a moment now stored in America’s alternate reality.The U.S. has resettled roughly 30,000 refugees since the start of the fiscal year in October, so a maximum 20,000 more refugees would be let in during Trump’s first year in office.More likely is that the U.S. falls below that threshold, as it did in the wake of 9/11. In 2002, the U.S. resettled 27,000 out of a possible 70,000 refugees authorized by the president.The need then, though considerable, hardly matches today’s crisis, which shows few signs of slowing with fewer wealthy countries willing to open their borders.Laurence Chandy, a fellow at the Brookings Institution studying global migration took a broad view of Trump’s executive actions. “The whole spirit of multilateralism is on life support,” Chandy said. He pointed to Trump’s quixotic criticism of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to receive more than 1 million refugees as an indication of the sort of approach Trump could take toward global crises and humanitarian needs.“Normally you’d want to heap praise on some other country for taking on a larger share of this global burden,” Chandy said, “but Trump doesn’t think about global problems needing to be globally shared.”Correction (10:05 a.m.): A previous version of this story gave the incorrect year for the start of Reagan’s first presidential term. It was 1981, not 1980.

After a slow start, President Obama pushed the 2017 goal to 110,000 total refugees in his final remarks to the United Nations in September, a nearly 30 percent increase from the year before. Hillary Clinton that same day said she would take in 65,000 more Syrian refugees if she were to become president — a moment now stored in America’s alternate reality.The U.S. has resettled roughly 30,000 refugees since the start of the fiscal year in October, so a maximum 20,000 more refugees would be let in during Trump’s first year in office.More likely is that the U.S. falls below that threshold, as it did in the wake of 9/11. In 2002, the U.S. resettled 27,000 out of a possible 70,000 refugees authorized by the president.The need then, though considerable, hardly matches today’s crisis, which shows few signs of slowing with fewer wealthy countries willing to open their borders.Laurence Chandy, a fellow at the Brookings Institution studying global migration took a broad view of Trump’s executive actions. “The whole spirit of multilateralism is on life support,” Chandy said. He pointed to Trump’s quixotic criticism of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to receive more than 1 million refugees as an indication of the sort of approach Trump could take toward global crises and humanitarian needs.“Normally you’d want to heap praise on some other country for taking on a larger share of this global burden,” Chandy said, “but Trump doesn’t think about global problems needing to be globally shared.”Correction (10:05 a.m.): A previous version of this story gave the incorrect year for the start of Reagan’s first presidential term. It was 1981, not 1980.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement