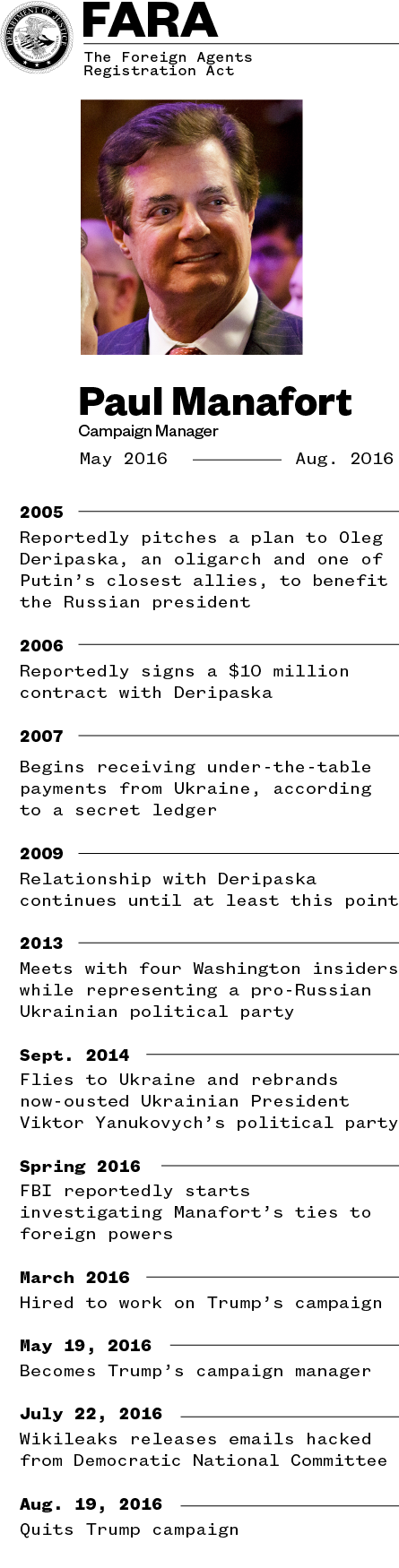

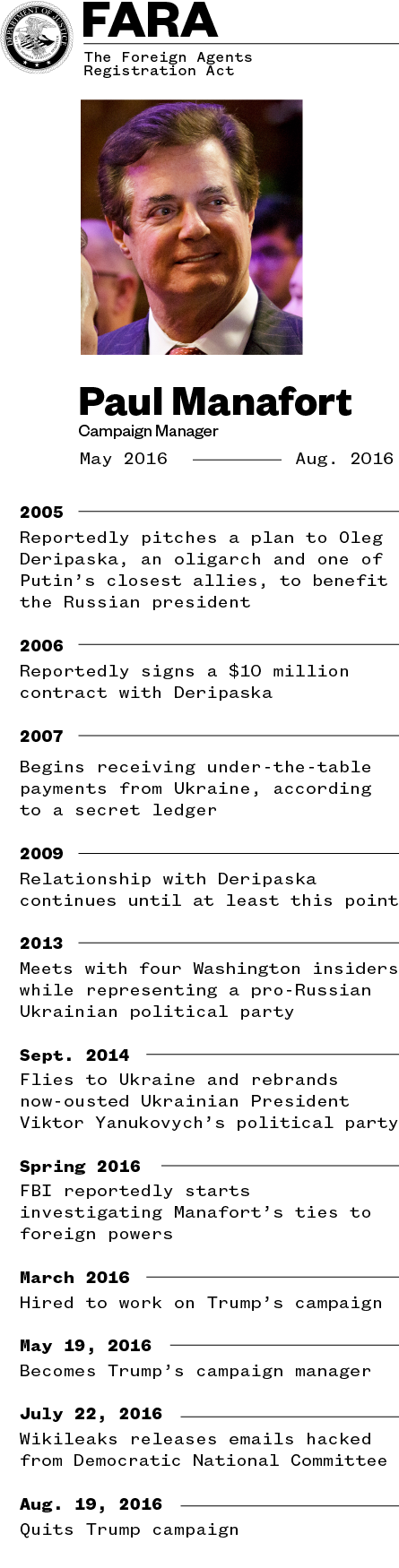

Rep. Dana Rohrabacher can’t remember if he knew Paul Manafort was working for a pro-Russian political party in Ukraine when the two old friends got together in March 2013. But the California Republican lawmaker is sure that Russia came up in their conversation.“He invited me to join him for dinner to catch up,” said Rohrabacher, who had just become chairman of the House Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats. As it turns out, Rohrabacher, often called “Putin’s favorite Congressman,” had also been told by the FBI in 2012 that Russian spies were trying to recruit him as an “agent of influence.”Rohrabacher now jokes about Manafort’s motives for the meeting. “I always assume when I meet my old friends that perhaps they have a reason for wanting to get together,” he said.In 2013, Manafort, a political consultant, lobbyist, and favorite hire of dictators, had been working for the Party of Regions, the pro-Russian base of ousted Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, for nearly a decade.But at the time he shared the meal with Rohrabacher, he hadn’t registered as a foreign agent with the Department of Justice under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), as required of anyone in the U.S. acting politically on behalf of a foreign country. Four years later, and after serving as chairman of Donald Trump’s campaign, Manafort still hasn’t registered, although he announced plans to do so in April. Now, he’s at the center of a widening criminal investigation into possible collusion between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin.FARA was designed to prevent the kind of murky, undisclosed ties now plaguing Manafort and Trump’s former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, who both face scrutiny over their work for Russia. But since the law’s language was revised in 1966, the DOJ has brought only seven criminal cases, only one of which ended in a conviction. Instead, the DOJ often warns potential violators and allows them to register after the fact. While the changes to FARA gave American businesses more freedom to work with foreign governments, they also crippled the ability of the DOJ’s National Security Division to bring criminal charges under the law. In an audit released just months before the election last year, the Office of the Inspector General found field agents and investigators frustrated over the lack of criminal charges — and thus, the missed opportunities to deter future criminal behavior.FARA violations are just a piece of the investigation into Russian meddling in the U.S. election, now led by special counsel and former FBI Director Robert Mueller. So far, both Manafort and Flynn have received subpoenas for their financial records. And other officials in the Trump campaign made at least 18 undisclosed connections with Russian officials during the campaign, according to Reuters.While FARA likely won’t be a focus of the deepening probes, Mueller could keep charges in his sights. “The cases that [were brought] in history, they were either high-profile or involved some enemy of the state,” said Joshua Ian Rosenstein, partner at Sandler Reiff, a political law firm specializing in the regulation of advocacy. Manafort and Flynn’s ties to Russia could fit that bill.To bring charges against someone suspected of violating FARA, investigators need to answer three questions, each progressively harder to prove:Then, investigators have to prove the foreign agent didn’t register with the DOJ — even though they knew they had to. “The law is all about public disclosure of the bias,” said Ron Oleynik, head of the international trade practice at law giant Holland & Knight. “So if you go on TV, to the White House, etc., and you knowingly conceal your bias, that’s the problem.” Without proving willfulness, many FARA violations end in a slap on the wrist, like a fine, instead of time behind bars.

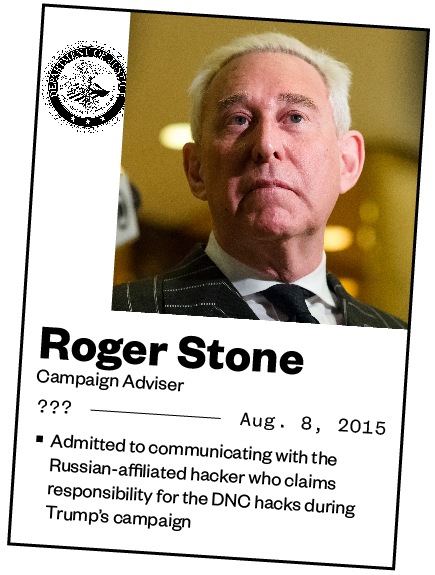

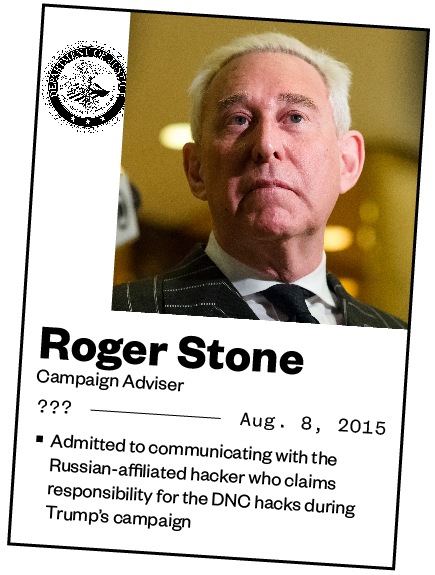

While the changes to FARA gave American businesses more freedom to work with foreign governments, they also crippled the ability of the DOJ’s National Security Division to bring criminal charges under the law. In an audit released just months before the election last year, the Office of the Inspector General found field agents and investigators frustrated over the lack of criminal charges — and thus, the missed opportunities to deter future criminal behavior.FARA violations are just a piece of the investigation into Russian meddling in the U.S. election, now led by special counsel and former FBI Director Robert Mueller. So far, both Manafort and Flynn have received subpoenas for their financial records. And other officials in the Trump campaign made at least 18 undisclosed connections with Russian officials during the campaign, according to Reuters.While FARA likely won’t be a focus of the deepening probes, Mueller could keep charges in his sights. “The cases that [were brought] in history, they were either high-profile or involved some enemy of the state,” said Joshua Ian Rosenstein, partner at Sandler Reiff, a political law firm specializing in the regulation of advocacy. Manafort and Flynn’s ties to Russia could fit that bill.To bring charges against someone suspected of violating FARA, investigators need to answer three questions, each progressively harder to prove:Then, investigators have to prove the foreign agent didn’t register with the DOJ — even though they knew they had to. “The law is all about public disclosure of the bias,” said Ron Oleynik, head of the international trade practice at law giant Holland & Knight. “So if you go on TV, to the White House, etc., and you knowingly conceal your bias, that’s the problem.” Without proving willfulness, many FARA violations end in a slap on the wrist, like a fine, instead of time behind bars. Manafort’s old lobbying firm — which he ran with onetime Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone — raked in millions of dollars representing foreign governments and filed the necessary FARA documents in the past. So it’s unlikely Manafort didn’t know he needed to inform the DOJ of his gig with the Party of Regions. It’s also possible he didn’t want anyone to know: Manafort allegedly kept payments from Ukraine to his consulting firm off the books using offshore accounts in Belize.In addition to his work for the Party of Regions, Manafort was also reportedly paid $10 million a year from 2006 until at least 2009 by Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska for a secret campaign intended to benefit Vladimir Putin’s government, according to the Associated Press. While Manafort acknowledged he worked for Deripaska, he said in March the work “did not involve representing Russia’s political interests.”While the DOJ often investigates FARA violations, much of the difficulty prosecuting them stems from amendments made to the law in 1966 — that’s when the DOJ started favoring voluntary compliance over criminal charges. For example, foreign agents can ask the DOJ how FARA would apply to work they did or might do. Now, the DOJ even notifies potential violators, although a National Security Division spokesperson said notification isn’t required. Before 1966, 23 criminal FARA trials ended in guilty verdicts. Since then, only one has, although other defendants have pleaded guilty.When Manafort’s lawyer, Jason Maloni, announced Manafort’s intent to retroactively register, he said Manafort had “received formal guidance recently from the authorities, and he is taking appropriate steps in response to the guidance.” Maloni declined to comment further.Communication with the DOJ gives potential violators a chance to register as foreign agents retroactively, bringing them into compliance with the law. The department’s Criminal Resource Manual even calls compliance the “cornerstone” of its enforcement efforts. But retroactive registry doesn’t mean someone didn’t violate the law. “It’s an admission of guilt in some ways,” Oleynik said. “You’ve gone out and registered under the very act that you’re accused of violating.”

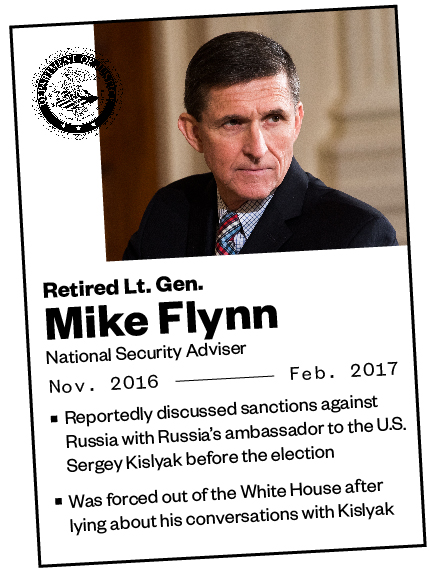

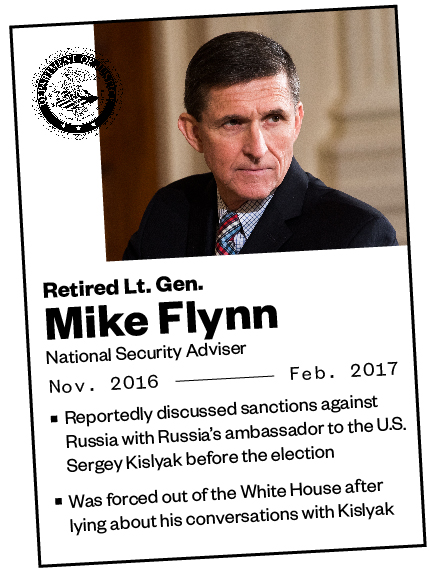

Manafort’s old lobbying firm — which he ran with onetime Trump campaign adviser Roger Stone — raked in millions of dollars representing foreign governments and filed the necessary FARA documents in the past. So it’s unlikely Manafort didn’t know he needed to inform the DOJ of his gig with the Party of Regions. It’s also possible he didn’t want anyone to know: Manafort allegedly kept payments from Ukraine to his consulting firm off the books using offshore accounts in Belize.In addition to his work for the Party of Regions, Manafort was also reportedly paid $10 million a year from 2006 until at least 2009 by Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska for a secret campaign intended to benefit Vladimir Putin’s government, according to the Associated Press. While Manafort acknowledged he worked for Deripaska, he said in March the work “did not involve representing Russia’s political interests.”While the DOJ often investigates FARA violations, much of the difficulty prosecuting them stems from amendments made to the law in 1966 — that’s when the DOJ started favoring voluntary compliance over criminal charges. For example, foreign agents can ask the DOJ how FARA would apply to work they did or might do. Now, the DOJ even notifies potential violators, although a National Security Division spokesperson said notification isn’t required. Before 1966, 23 criminal FARA trials ended in guilty verdicts. Since then, only one has, although other defendants have pleaded guilty.When Manafort’s lawyer, Jason Maloni, announced Manafort’s intent to retroactively register, he said Manafort had “received formal guidance recently from the authorities, and he is taking appropriate steps in response to the guidance.” Maloni declined to comment further.Communication with the DOJ gives potential violators a chance to register as foreign agents retroactively, bringing them into compliance with the law. The department’s Criminal Resource Manual even calls compliance the “cornerstone” of its enforcement efforts. But retroactive registry doesn’t mean someone didn’t violate the law. “It’s an admission of guilt in some ways,” Oleynik said. “You’ve gone out and registered under the very act that you’re accused of violating.” Then again, a foreign agent may have no reason to register with the DOJ if they think they’ll see a prison cell. So after registering, if they answer questions about who they were working for and hand over relevant documents, potential charges could disappear, Rosenstein said. The National Security Division doesn’t track how many cases they decline to prosecute, nor the reasons why, according to the Office of the Inspector General’s audit.There’s another reason for the government to avoid filing FARA charges: Prosecuting criminal FARA charges can risk revealing counterintelligence information or surveillance techniques the government wants to keep on the down-low.“There may be aspects of the case that you do not want to be declassified to prove that FARA violation because the actual information is more important than the prosecution,” said Bob Anderson, who served as executive assistant director of the FBI’s counterintelligence unit until December 2015.In addition to Manafort, Flynn has also been scrutinized over disclosure of his ties to foreign governments. In December 2015, with sanctions already levied against Russia, Flynn was paid $45,000 to attend and speak at the 10th anniversary celebration of state-owned network RT, where he sat next to Putin. Flynn, however, mislead the Pentagon about the event when he applied to renew his security clearance last year, according to a letter released Monday by the top Democrat on the House Oversight Committee. Flynn also reportedly discussed the sanctions — and whether Trump would repeal them — with Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. Sergey Kislyak, before the election. And then Flynn lied about that conversation, which helped fuel his exit from the White House after just 24 days. In March, almost a month after Flynn resigned from Trump’s Cabinet, he disclosed over half a million dollars of work he did before Election Day as a foreign agent of Turkey.

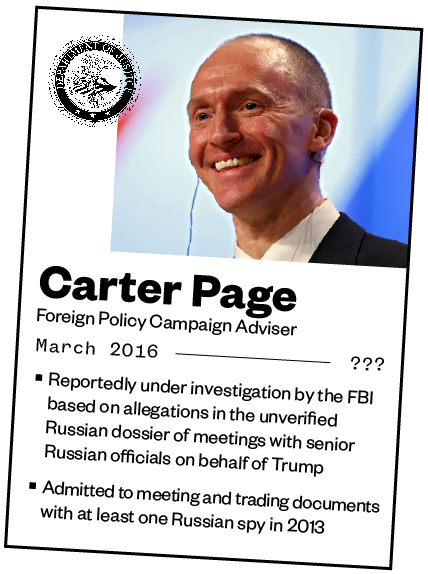

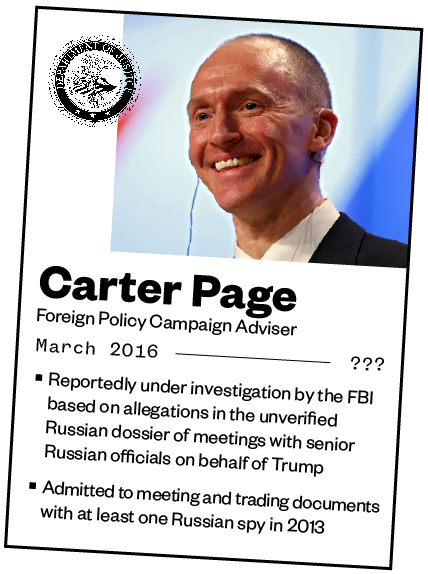

Then again, a foreign agent may have no reason to register with the DOJ if they think they’ll see a prison cell. So after registering, if they answer questions about who they were working for and hand over relevant documents, potential charges could disappear, Rosenstein said. The National Security Division doesn’t track how many cases they decline to prosecute, nor the reasons why, according to the Office of the Inspector General’s audit.There’s another reason for the government to avoid filing FARA charges: Prosecuting criminal FARA charges can risk revealing counterintelligence information or surveillance techniques the government wants to keep on the down-low.“There may be aspects of the case that you do not want to be declassified to prove that FARA violation because the actual information is more important than the prosecution,” said Bob Anderson, who served as executive assistant director of the FBI’s counterintelligence unit until December 2015.In addition to Manafort, Flynn has also been scrutinized over disclosure of his ties to foreign governments. In December 2015, with sanctions already levied against Russia, Flynn was paid $45,000 to attend and speak at the 10th anniversary celebration of state-owned network RT, where he sat next to Putin. Flynn, however, mislead the Pentagon about the event when he applied to renew his security clearance last year, according to a letter released Monday by the top Democrat on the House Oversight Committee. Flynn also reportedly discussed the sanctions — and whether Trump would repeal them — with Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. Sergey Kislyak, before the election. And then Flynn lied about that conversation, which helped fuel his exit from the White House after just 24 days. In March, almost a month after Flynn resigned from Trump’s Cabinet, he disclosed over half a million dollars of work he did before Election Day as a foreign agent of Turkey. Flynn volunteered to testify in front of the Senate in exchange for immunity, which lawmakers reportedly rejected. Then, in a letter obtained by the Associated Press on Monday, Flynn’s lawyer rejected a Congressional subpoena, citing Flynn’s Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. His lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment.Although neither has offered to register under FARA, allegations of ties to Russia also plague former Trump campaign advisers Roger Stone and Carter Page. The FBI reportedly obtained a warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to surveil Page based on allegations of ties to Russia contained in the explosive dossier made public in January. The documents allege that Page met with senior Russian officials to discuss the sanctions on behalf of the Trump campaign.While Page calls the allegations “such a joke that it’s beyond words,” he did admit to meeting and trading documents, which he claims were publicly available, with at least one Russian spy in 2013. During the campaign in July, Page also gave a graduation speech critical of the U.S. at a prestigious Moscow Institute, which reportedly caught the FBI’s attention.Stone also admitted to communicating during Trump’s campaign with a Russian-affiliated hacker named “Guccifer 2.0,” who claims responsibility for the DNC hacks. But Stone called their conversations “completely innocuous.”The Senate Intelligence Committee has asked both Stone and Page to preserve records and testify during hearings. They’ve both also volunteered to testify in front of the House.In its audit critical of FARA enforcement, the Office of the Inspector General gave the National Security Division until March 31 to make more information about charges available to the public as well as establish a strategy for investigating noncompliant foreign agents.When asked, a spokesperson for the National Security Division said the department “is in the process” of creating a document that explains their “comprehensive strategy.”

Flynn volunteered to testify in front of the Senate in exchange for immunity, which lawmakers reportedly rejected. Then, in a letter obtained by the Associated Press on Monday, Flynn’s lawyer rejected a Congressional subpoena, citing Flynn’s Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. His lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment.Although neither has offered to register under FARA, allegations of ties to Russia also plague former Trump campaign advisers Roger Stone and Carter Page. The FBI reportedly obtained a warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to surveil Page based on allegations of ties to Russia contained in the explosive dossier made public in January. The documents allege that Page met with senior Russian officials to discuss the sanctions on behalf of the Trump campaign.While Page calls the allegations “such a joke that it’s beyond words,” he did admit to meeting and trading documents, which he claims were publicly available, with at least one Russian spy in 2013. During the campaign in July, Page also gave a graduation speech critical of the U.S. at a prestigious Moscow Institute, which reportedly caught the FBI’s attention.Stone also admitted to communicating during Trump’s campaign with a Russian-affiliated hacker named “Guccifer 2.0,” who claims responsibility for the DNC hacks. But Stone called their conversations “completely innocuous.”The Senate Intelligence Committee has asked both Stone and Page to preserve records and testify during hearings. They’ve both also volunteered to testify in front of the House.In its audit critical of FARA enforcement, the Office of the Inspector General gave the National Security Division until March 31 to make more information about charges available to the public as well as establish a strategy for investigating noncompliant foreign agents.When asked, a spokesperson for the National Security Division said the department “is in the process” of creating a document that explains their “comprehensive strategy.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

- Did someone lobby about an issue? Certain media work, like public relations, is also housed under the statute.

- Did they do it on behalf of a foreign government? (They don’t need to be paid.)

- And finally, did they willfully fail to register with the Department of Justice?

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement