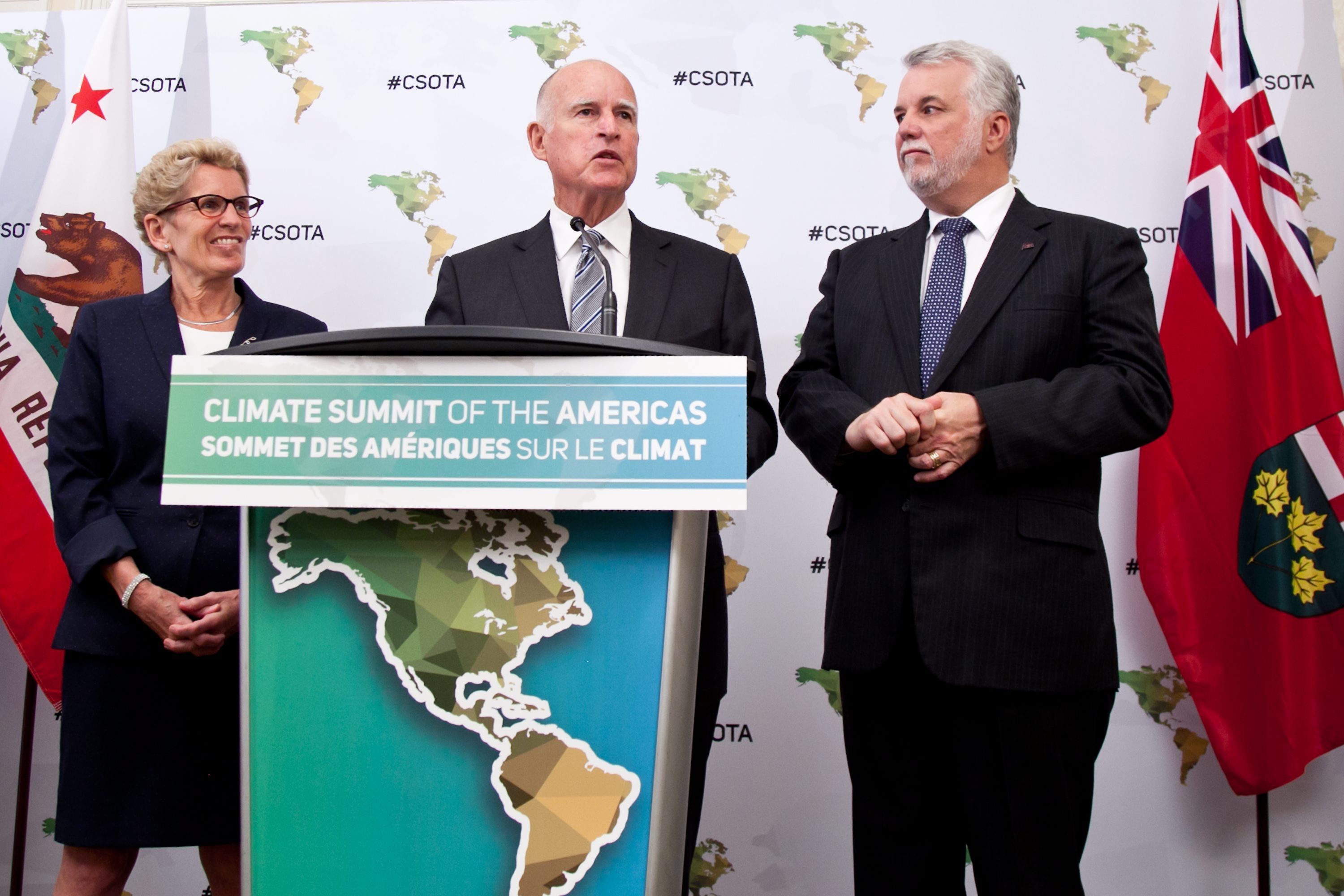

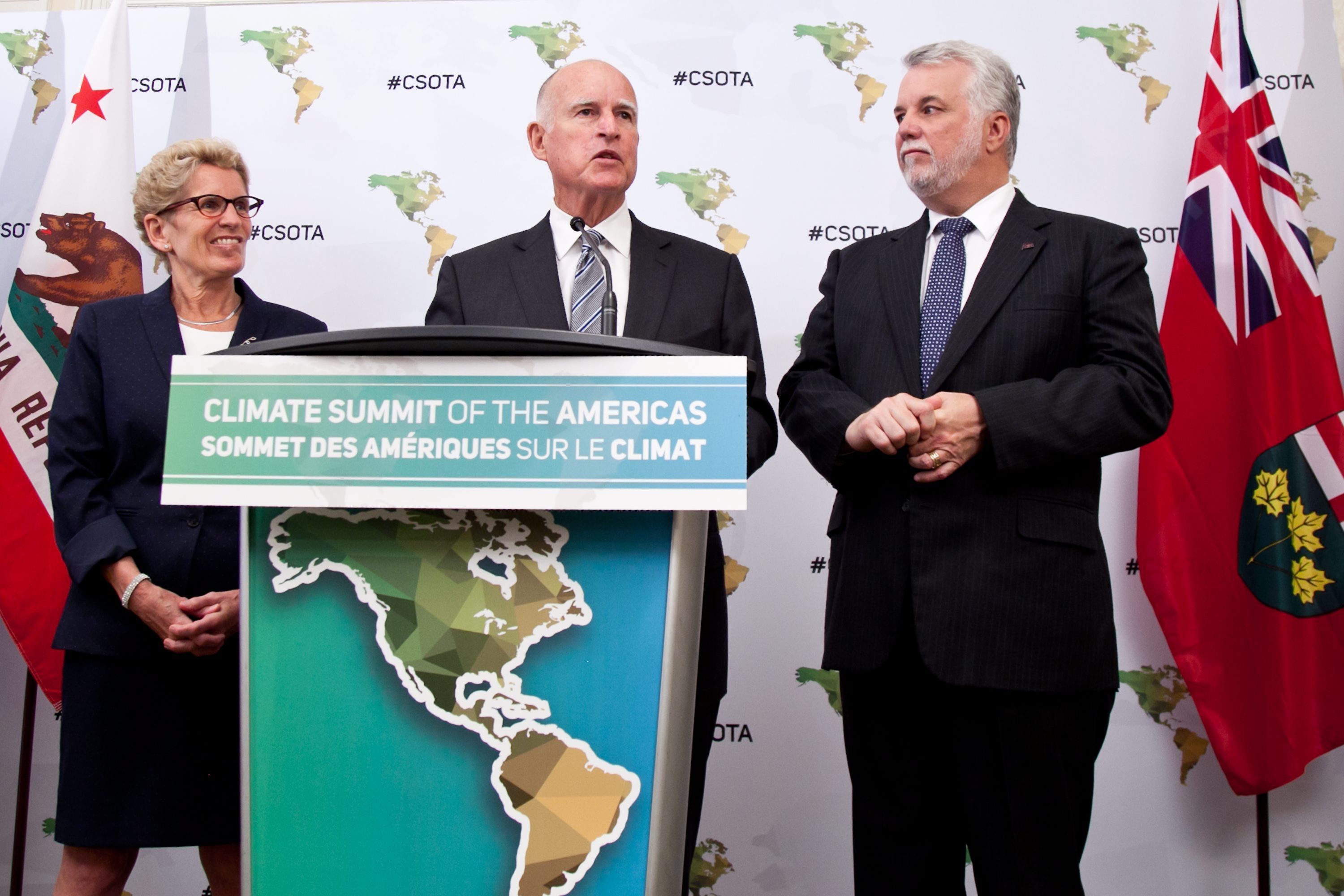

By most accounts, the North American carbon pricing market is a huge success.Beginning in California and Quebec in 2014, the ambitious cap and trade model now covers more than 60 million people and $3 trillion in annual GDP, with the addition, just days ago, of Ontario.In short, the model caps carbon emissions, and then enables companies to burn more than their share of carbon by buying permits from companies that burn less.By one count, emissions in California directly targeted by the regime have declined 3 percent, even as the economy has grown in the state, and has generated $4 billion for government initiatives. In Canada, the Quebec program has raised more than $1 billion in revenue, while Ontario is already budgeting for $2 billion in annual revenue, earmarking it for climate change-fighting initiatives.Mexico, meanwhile, is launching a cap and trade pilot program with an eye to joining the North American-wide market by 2018.There’s just one problem: many signs point to an entire market that is teetering on the brink of collapse.A cap and trade market is a simple question of supply and demand.In each jurisdiction, the government sets an emission cap. If a business falls below that cap, the system doesn’t impact them. If they emit over the cap, they’ll need to cover that excess with carbon allocations, or permits, at auction — each tonne could run, at current prices, from $12 to $48.Each government allocates a quantity of free permits. If a company doesn’t need all of those permits, it can sell them elsewhere and pocket the revenue.As time goes on, the emission cap will progressively lower — requiring businesses to either reduce their pollution output or buy more permits. Free permits will become increasingly rare and, as a result, the market will raise the cost of permits in the auction.Can’t find enough permits? You’ll pay the government directly for any pollution that isn’t covered.Cap and trade was heralded as a more progressive and effective way to reduce pollution, as opposed to a carbon tax — a regressive penalty that has been dubbed a ‘tax on everything.’When the joint market first opened, the permits sold like hot cakes. At the first auction, in 2014, the market was over-bid by about 15 percent, meaning there was competition for the pollution credits, most of which were sold directly by the two governments — although there was some credit trading between companies.That chugged along for more than a year, with five subsequent auctions selling every single available carbon credit.That ended in May of 2016, as the demand for those credits simply dried up. The joint market sold just 10 percent of its available permits.California expected $500 million in revenue from the auction. It got $10 million.Quebec, for its part, has raked in little revenue, as it has handed out many of the permits for free in order to avoid the flight of businesses operating in the province.By August, things had improved slightly, but it was still a disaster. Barely a third of all the permits were sold. In a year, the continent-stretching market had shrunk by half. Exacerbating the problem is that program couldn’t even get companies to buy the government-issued credits. Instead, companies were trading amongst each other — bad news for government revenue.Things have begun to turn around, however. The most recent auction, held in November, was far more promising. Nearly 90 percent of the available permits were sold.Environmental Defence, a Canadian environmental organization, heralded the news: “A pretty significant comeback, kid.”But there are lingering doubts about the future of the market, even if the current trade is recovering.

At the first auction, in 2014, the market was over-bid by about 15 percent, meaning there was competition for the pollution credits, most of which were sold directly by the two governments — although there was some credit trading between companies.That chugged along for more than a year, with five subsequent auctions selling every single available carbon credit.That ended in May of 2016, as the demand for those credits simply dried up. The joint market sold just 10 percent of its available permits.California expected $500 million in revenue from the auction. It got $10 million.Quebec, for its part, has raked in little revenue, as it has handed out many of the permits for free in order to avoid the flight of businesses operating in the province.By August, things had improved slightly, but it was still a disaster. Barely a third of all the permits were sold. In a year, the continent-stretching market had shrunk by half. Exacerbating the problem is that program couldn’t even get companies to buy the government-issued credits. Instead, companies were trading amongst each other — bad news for government revenue.Things have begun to turn around, however. The most recent auction, held in November, was far more promising. Nearly 90 percent of the available permits were sold.Environmental Defence, a Canadian environmental organization, heralded the news: “A pretty significant comeback, kid.”But there are lingering doubts about the future of the market, even if the current trade is recovering. Both California and Quebec developed a futures market in parallel to the current regime. It allowed polluters to buy emission credits three years into the future, but at current prices. For big polluters, the option was cheap way to buy time to reduce their footprint. For others, it could prove a sturdy investment, as they could sell the credits in the future at a profit.The price for futures has fluctuated since the market’s inception, opening at more than $20, dropping as low as $11.50, where it has largely stayed since 2014. The price in early January was hovering just below $12.Trading in futures, after months of furious action, ground to a halt last May, plunging by some 90 percent. Even as the market recovered, in November, just a tenth of the future permits were sold at auction.The ebb and flow of the market, and the slowing of government revenues, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, depending on who you ask.“The answer is simple,” Chris Busch, Director of Research at green thinktank Energy Innovation, wrote in a blog post. “Other climate and energy policies are lowering emissions, reducing the need for emitters covered under the cap-and-trade program to acquire allowances.”Busch contends that the market was never intended just as a cash cow, and that low prices for the carbon offsets aren’t, in and of themselves, bad news.But the entire point of creating the market for carbon offsets is to adjust the availability of permits, and to lower the emissions cap, so as to drive demand and keep prices for the permits from becoming too cheap. But with the prices flat, and with a general lack of competition for the permits, there are still signs of trouble.

Both California and Quebec developed a futures market in parallel to the current regime. It allowed polluters to buy emission credits three years into the future, but at current prices. For big polluters, the option was cheap way to buy time to reduce their footprint. For others, it could prove a sturdy investment, as they could sell the credits in the future at a profit.The price for futures has fluctuated since the market’s inception, opening at more than $20, dropping as low as $11.50, where it has largely stayed since 2014. The price in early January was hovering just below $12.Trading in futures, after months of furious action, ground to a halt last May, plunging by some 90 percent. Even as the market recovered, in November, just a tenth of the future permits were sold at auction.The ebb and flow of the market, and the slowing of government revenues, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, depending on who you ask.“The answer is simple,” Chris Busch, Director of Research at green thinktank Energy Innovation, wrote in a blog post. “Other climate and energy policies are lowering emissions, reducing the need for emitters covered under the cap-and-trade program to acquire allowances.”Busch contends that the market was never intended just as a cash cow, and that low prices for the carbon offsets aren’t, in and of themselves, bad news.But the entire point of creating the market for carbon offsets is to adjust the availability of permits, and to lower the emissions cap, so as to drive demand and keep prices for the permits from becoming too cheap. But with the prices flat, and with a general lack of competition for the permits, there are still signs of trouble. The European Union ran head-long into this problem. They’ve refused to reduce the number of permits in the market, which would hike prices, resulting in a glut of dirt-cheap credits. That has led many, including the Economist magazine, to declare its cap and trade system “a mess.”The price for a credit, which covers a tonne of carbon emissions, fell from €25 per tonne in 2008 to just €6 per tonne today.That problem could be in store for the North American system, if scarcity isn’t brought back into the system. But there’s some good news to that end: The floor price for the North American credits is slated to rise this year to $13.50 a tonne.There’s another problem at the heart of the market, especially in California — nobody knows whether the market will exist in three years.Other states and provinces, like British Columbia and Manitoba, have passed on joining the joint market, while a national carbon market championed by President Barack Obama has been delayed and kneecapped in both the courts and Congress and now seems doomed by the incoming administration.Meanwhile, a lawsuit filed in a California court seeks to axe that state’s market altogether. The California Chamber of Commerce, a long-time enemy of the market, argues that the cap and trade system is, in essence, a tax, and that California’s constitution requires a supermajority (two-thirds of both houses of the legislature) to pass new taxes.A lower court has already ruled that the carbon market is not a tax, and is therefore constitutional, but a court of appeal has yet to weigh in.The market will also require re-authorization to continue operating past 2020, a prospect that is anything but certain. That uncertainty is bad news — California is a large majority of the market and, without it, the two Canadian provinces may well just abandon the system altogether.

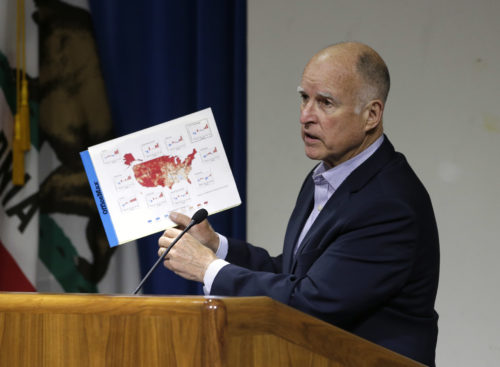

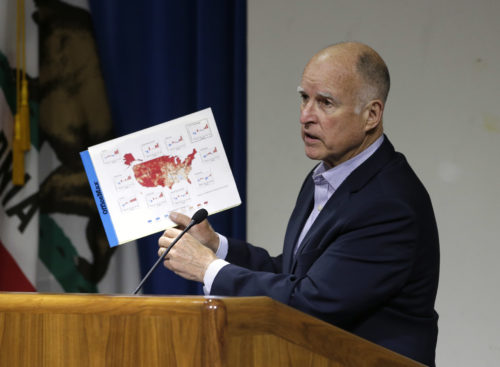

The European Union ran head-long into this problem. They’ve refused to reduce the number of permits in the market, which would hike prices, resulting in a glut of dirt-cheap credits. That has led many, including the Economist magazine, to declare its cap and trade system “a mess.”The price for a credit, which covers a tonne of carbon emissions, fell from €25 per tonne in 2008 to just €6 per tonne today.That problem could be in store for the North American system, if scarcity isn’t brought back into the system. But there’s some good news to that end: The floor price for the North American credits is slated to rise this year to $13.50 a tonne.There’s another problem at the heart of the market, especially in California — nobody knows whether the market will exist in three years.Other states and provinces, like British Columbia and Manitoba, have passed on joining the joint market, while a national carbon market championed by President Barack Obama has been delayed and kneecapped in both the courts and Congress and now seems doomed by the incoming administration.Meanwhile, a lawsuit filed in a California court seeks to axe that state’s market altogether. The California Chamber of Commerce, a long-time enemy of the market, argues that the cap and trade system is, in essence, a tax, and that California’s constitution requires a supermajority (two-thirds of both houses of the legislature) to pass new taxes.A lower court has already ruled that the carbon market is not a tax, and is therefore constitutional, but a court of appeal has yet to weigh in.The market will also require re-authorization to continue operating past 2020, a prospect that is anything but certain. That uncertainty is bad news — California is a large majority of the market and, without it, the two Canadian provinces may well just abandon the system altogether. If cap and trade is a failed experiment, someone forgot to tell China.The Communist regime ordered a pilot project as part of a five year plan to establish seven emission trading markets in seven different provinces. A national market is expected to follow, and is an integral part of China’s effort to scale back its carbon output.While it’s still too early to tell whether the Chinese model will work, they have the benefit of hindsight in knowing what has worked and what has failed.Even the EU, with its flawed system, has cut carbon emissions by 20 percent below 1990 emission levels by 2020, thanks in no small part to cap and trade.And despite vocal opposition to a national American system, the US already has experience successfully deploying cap and trade.The 1990 Clean Air Act, introduced by George H. W. Bush, established an emission-trading program for sulfur dioxide and other emissions, allowing emitters of the dangerous emissions to buy and sell permits much in the way that California and Quebec are doing now.“The program was a great success by almost all measures,” reads a 2012 report from the Harvard Environmental Economics Program.The report concluded that a breakdown in bipartisan political cooperation in the United States was the main barrier between the successes of the Clean Air Act and similar victories in tackling greenhouse gasses.“It is likely that at least as much bipartisan collaboration would be required as was evident in the [Clean Air Act] process,” the final report concludes.“Instead, we have much less.”

If cap and trade is a failed experiment, someone forgot to tell China.The Communist regime ordered a pilot project as part of a five year plan to establish seven emission trading markets in seven different provinces. A national market is expected to follow, and is an integral part of China’s effort to scale back its carbon output.While it’s still too early to tell whether the Chinese model will work, they have the benefit of hindsight in knowing what has worked and what has failed.Even the EU, with its flawed system, has cut carbon emissions by 20 percent below 1990 emission levels by 2020, thanks in no small part to cap and trade.And despite vocal opposition to a national American system, the US already has experience successfully deploying cap and trade.The 1990 Clean Air Act, introduced by George H. W. Bush, established an emission-trading program for sulfur dioxide and other emissions, allowing emitters of the dangerous emissions to buy and sell permits much in the way that California and Quebec are doing now.“The program was a great success by almost all measures,” reads a 2012 report from the Harvard Environmental Economics Program.The report concluded that a breakdown in bipartisan political cooperation in the United States was the main barrier between the successes of the Clean Air Act and similar victories in tackling greenhouse gasses.“It is likely that at least as much bipartisan collaboration would be required as was evident in the [Clean Air Act] process,” the final report concludes.“Instead, we have much less.”

Advertisement

Cap and Trade basics

Advertisement

From 100% to 10%

Advertisement

Too successful?

Advertisement

Advertisement

Is cap and trade dead?

Advertisement