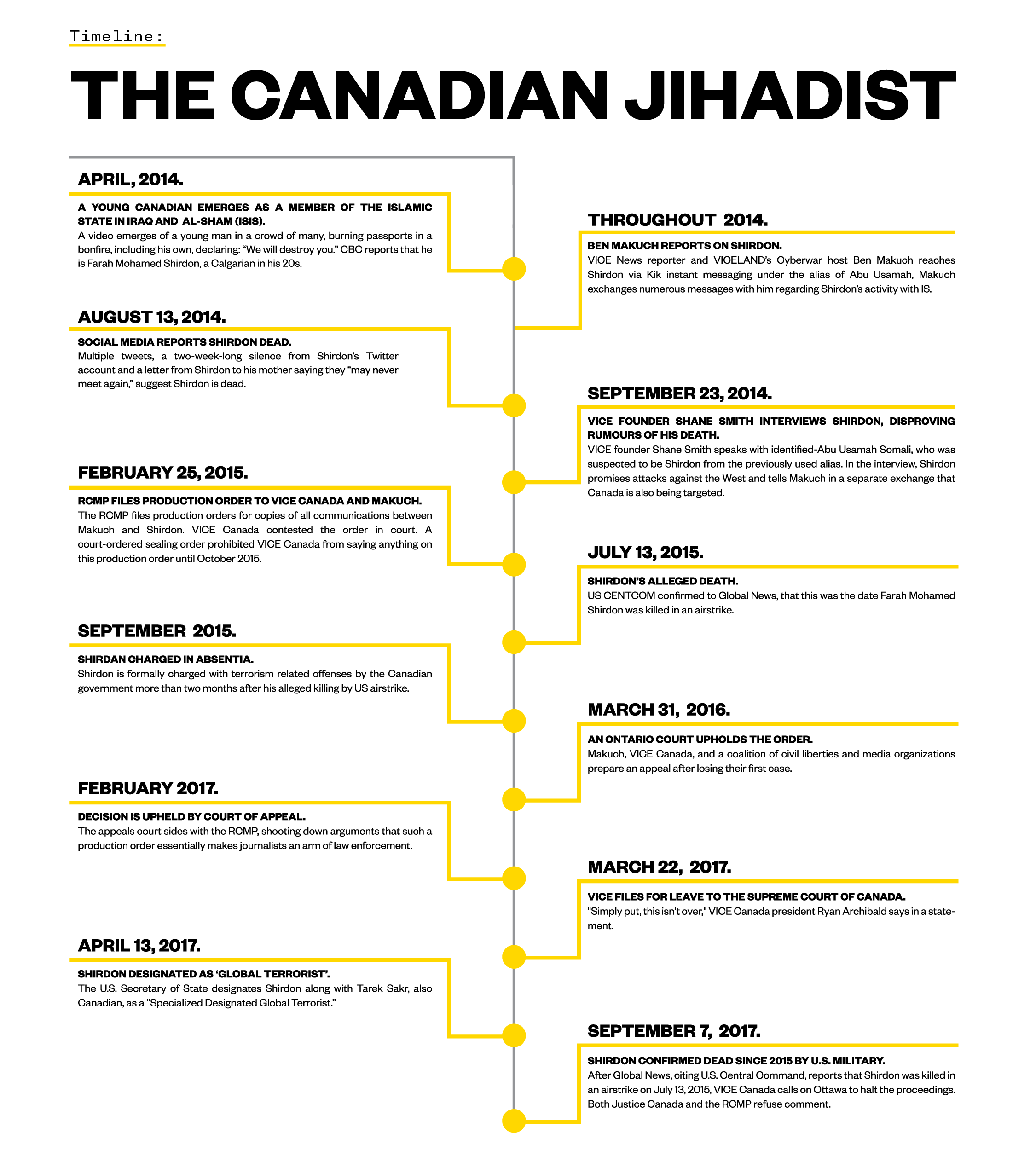

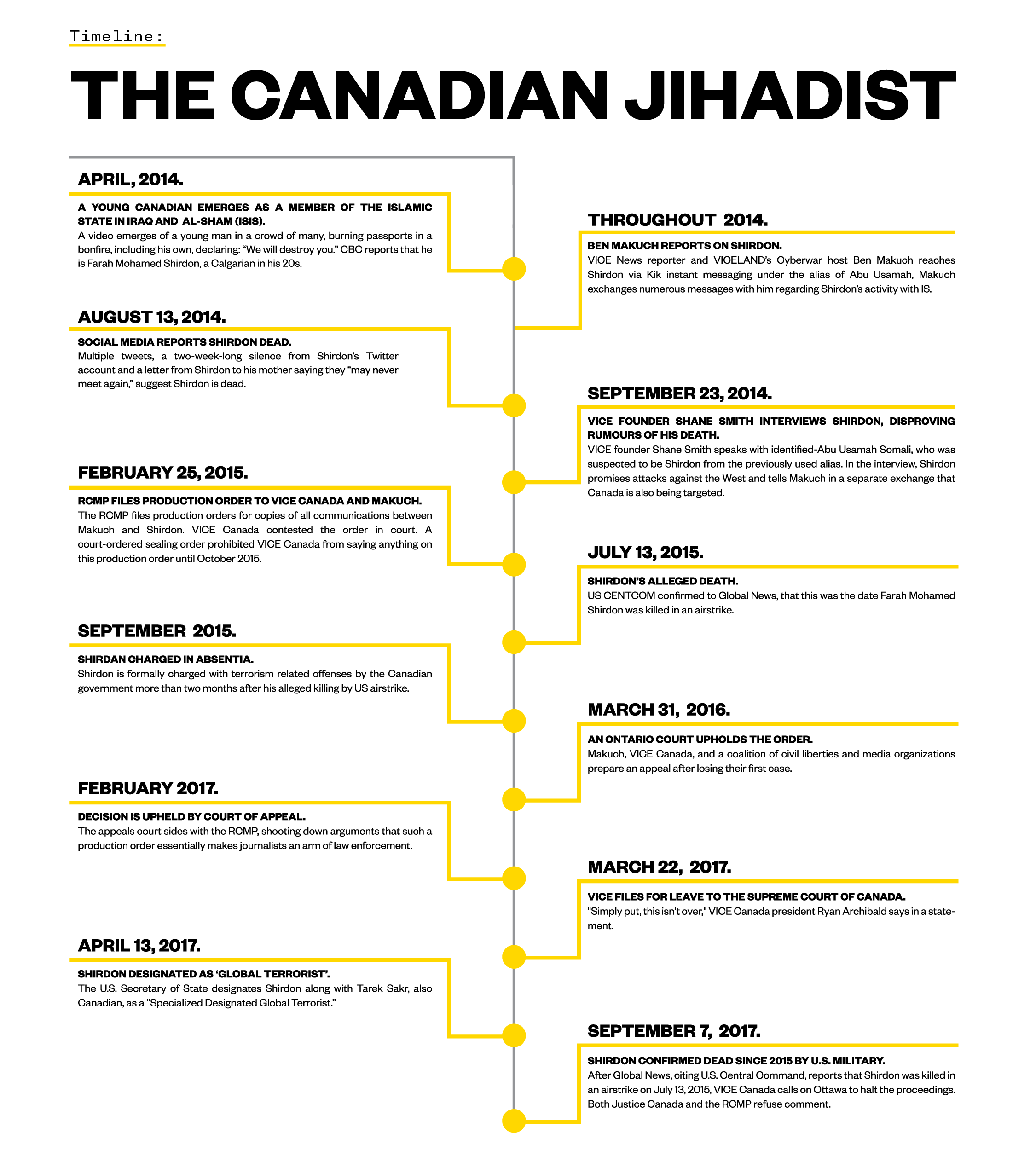

Back in the summer of 2014, Farah Mohamed Shirdon, the alleged Islamic State operative from Calgary, Alberta who went by the war name “Abu Usamah” to me, was supposed to have been dead.I even reported on it using jihadist sources I cultivated during the rise of the so-called caliphate in Iraq and Syria, way back before the Islamic State became the western bogeyman du jour.At the time, I wrote that regardless of how you felt about an avowed terrorist, his online life gave “a very clear portrait: The beginning of his career as an IS fighter, the middle, and tragically now, the end.”Of course, a few weeks later he reemerged alive and well, even texting me to prove it.That’s why seeing the latest report by Global News indicating he’s not only dead, but the U.S. military targeted and eliminated him in an airstrike on July 13, 2015, is a little surreal. And even makes me wonder if they got the date of his death correct.For one, the RCMP has carried out a lengthy and expensive legal battle against me to disclose my extensive conversations with Shirdon over Kik messenger service for the better part of a year and a half. I wrote a few stories from our online exchanges, one on how Shirdon joined IS and recruited for them and another where he threatened Canada.Right now, I’m awaiting word from the Supreme Court of Canada on whether or not they’ll hear my case in a ruling that could potentially be a precedent-setting case pitting police powers versus freedom of the press in this country.VICE Canada, for its part, released a statement yesterday afternoon calling on Ottawa to drop the case, in light of confirmation of Shirdon’s death.So the real question becomes: How long has the RCMP known about his potential demise at the hands of an American missile and, if so, why have they continued to pursue me? Because if the U.S. Army is to be believed, which is at the head of an international coalition fighting ISIS that Canada is a part of, this was potentially over a long time ago.In July of 2015, I was still under a gag order to keep all details of the case private, which lasted until October 2015, after they charged Shirdon formally and in absentia.By that point, Shirdon had — by the U.S. Army indications — been dead for close to three months.Amarnath Amarasingam, a researcher with extensive contacts with IS fighters, thinks his death date is fishy and likely too early.He told Global News: “The date seems pretty questionable to me,” and that a source he had spoke to Shirdon in 2016 about “fairly personal things, so it’s unlikely that it was an imposter.”My last exchanges with Shirdon were in late April 2015. Judging by those text messages, Shirdon seemed erratic and I got the feeling he may have gotten into trouble with IS authorities for speaking with me. Many of his texts then were essays with wild allegations and observations about my career that came in random clusters late at night.After that, he never replied to me again, but in November 2016 messages I sent to Shirdon’s alleged profile — the same one he used as a point of contact in previous interviews along with the device he uses to engage on the platform — generated “delivered” confirmations.Then he went dark again.One source has since said rumours were swirling Shirdon went to Somalia, which seemed unlikely even if he had family connections there, given he was a very recognizable man on an Interpol most-wanted list travelling thousands of kilometers without detection.If the continued legal battle is any indication, the fact that Canadian intelligence and law enforcement potentially didn’t receive information on one of the country’s most wanted terrorists being killed in an airstrike by its biggest ally and world power, is suspicious. As early as June 2014, I appeared in an intelligence report with Shirdon. And those reports — Canadian terror assessments, which CSIS and the RCMP help compile — are known to be shared with U.S. partners. The terror assessment in question likely didn’t contain any caveats that would have limited its sharing outside of Canada.It’s definitely noteworthy if CSIS wasn’t told by the U.S. spooks of a potential killing of one of its citizens, for over two years, who was at the time considered a top English language recruiter and propagandist for IS.Justice Canada directed questions about the ongoing court case to the RCMP. The RCMP refused comment, saying only they were “aware of the reports circulating in Canadian media that Shirdon may have been killed.”

As early as June 2014, I appeared in an intelligence report with Shirdon. And those reports — Canadian terror assessments, which CSIS and the RCMP help compile — are known to be shared with U.S. partners. The terror assessment in question likely didn’t contain any caveats that would have limited its sharing outside of Canada.It’s definitely noteworthy if CSIS wasn’t told by the U.S. spooks of a potential killing of one of its citizens, for over two years, who was at the time considered a top English language recruiter and propagandist for IS.Justice Canada directed questions about the ongoing court case to the RCMP. The RCMP refused comment, saying only they were “aware of the reports circulating in Canadian media that Shirdon may have been killed.” With files from Sarah Krichel

With files from Sarah Krichel

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement