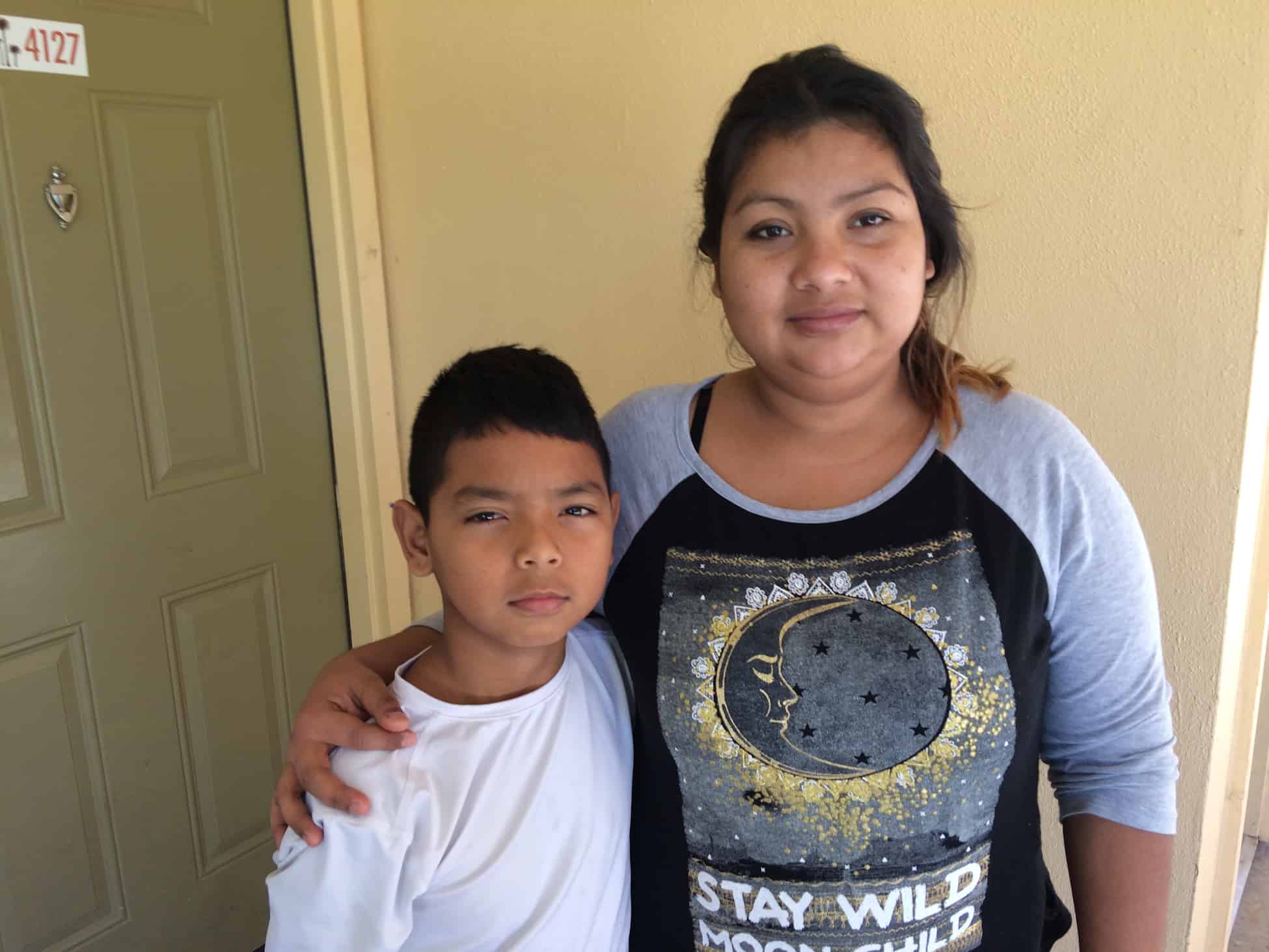

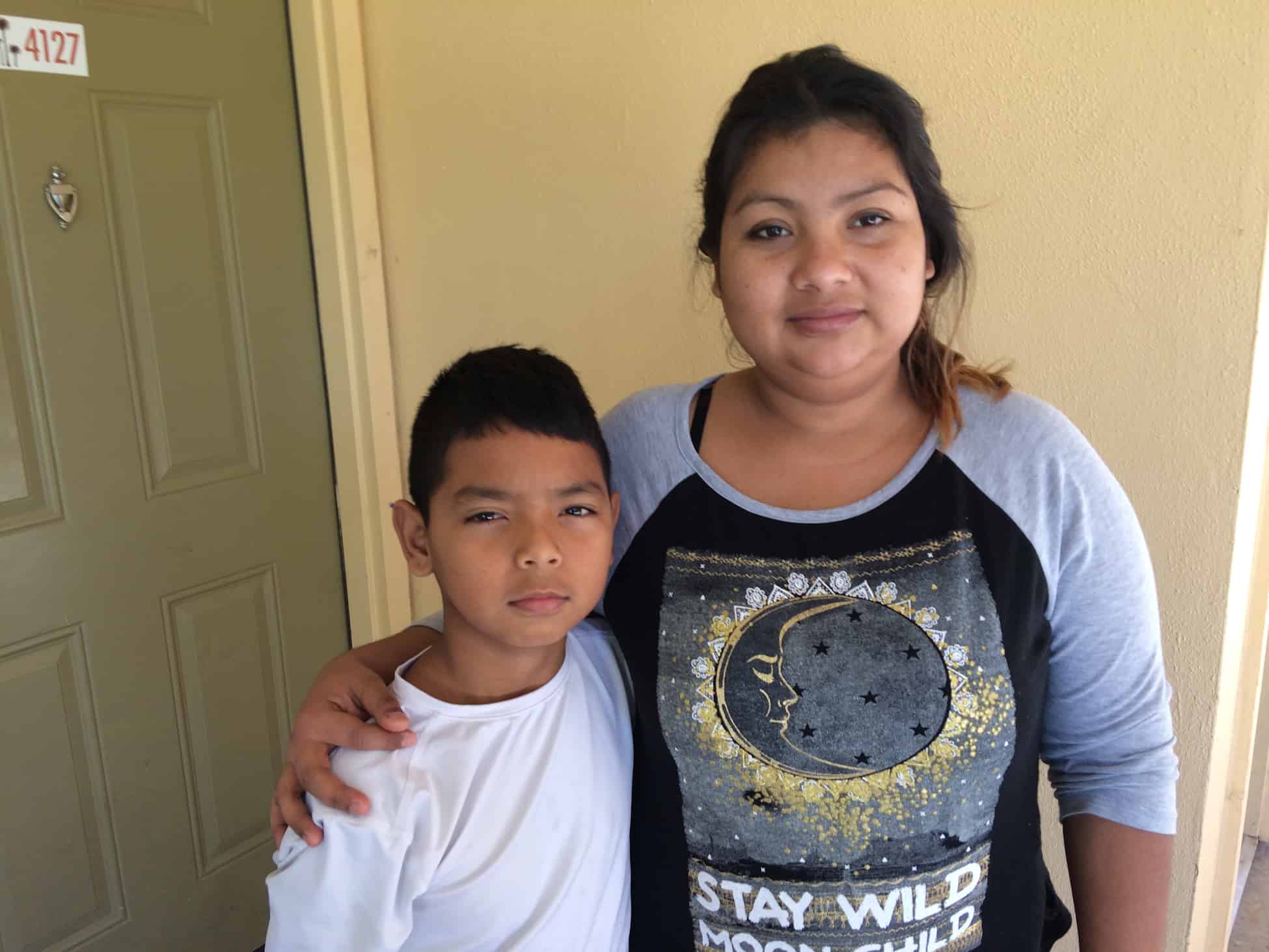

When Ana’s husband threatened to kill her and her 10-year-old son, she decided to run. So she left her home in Honduras with her son, Cesar, and began an eight-day journey north, reaching Mexico’s border with the U.S. in late January.Once there, she approached U.S. Customs agents at the Delrio, Texas, border crossing and requested asylum. The agents agreed to bring Ana and Cesar into the country and begin the process of determining whether they qualified — but they also separated the mother and son, sending Ana to an adult detention center and Cesar to a facility for unaccompanied minors.“They told me we’d be separated, and I asked why, but they didn’t explain,” said the 29-year-old mom, who asked that her last name not be used because her case is still being processed. In detention, she was unable to talk to Cesar and tormented by rumors circulating among inmates that the U.S. planned to keep immigrant children in the country while deporting their mothers.“I cried day and night, thinking, ‘Why did I come to this country?’”Today it’s tougher than ever for immigrant families seeking asylum in the U.S. They face more frequent turnarounds — on-the-spot denials of the opportunity to enter the country and seek asylum — by U.S. Customs agents at the border, and new harsher standards once the asylum process begins. They must also contend with frightening rumors about how the new administration will treat families; while the rumors are often overblown, they also often have a basis in fact. There has been a dramatic drop in the number of families arriving at the U.S. border, though the exact reasons for that remain unclear. The Department of Homeland Security reported in early April a 93 percent drop in the number of children and parents caught trying to enter the U.S. illegally.There are currently just 305 inmates in South Texas’ two family immigrant detention centers, according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement; the centers have enough beds for 3,600, and they were almost constantly filled as recently as 2015. In March, 12,000 people were apprehended at the border — a 63 percent drop from last March, according to Customs and Border Protection.The dip in arrivals means more families are enduring the threat of extreme harm at home — many are fleeing ongoing gang violence in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala — because they’re worried things would be even worse in the U.S., says Denise Gilman, director of the University of Texas’ Immigration Law Clinic.“The situation on the ground in Central America hasn’t changed at all,” Gilman said. “People are still suffering greatly as a result of widespread violence and human rights violations. So the lower number of individuals seeking asylum at the border is just an indicator of how dramatic the cruelty is in the steps that have been announced [by the U.S.].”Even though America is legally bound to allow asylum seekers who appear at the border into the country, immigration agents began flatly turning some away after the election, according to advocates who work on the border. Nicole Ramos, project coordinator for the Border Rights Project, which works with asylum seekers in Tijuana, Mexico, said she frequently encounters asylum seekers who were denied entry into the U.S.The news of such rejections, and of Trump’s refugee bans, prompted many prospective asylum seekers to stop even trying to enter the country because they believe they, too, will be turned away. (A refugee ban could not stop the U.S. from accepting asylum seekers who arrive at the border.)“Many are confused because of the talk about the refugee ban, about whether it applies to asylum seekers,” Ramos said. “I’ve heard confusion from asylum seekers and also staff at different shelters.”Families have been distraught over the separation of mothers and children, a policy DHS Secretary John Kelly announced last month, saying he planned to implement it on a large scale in order to deter families from attempting to enter the country. But he later reversed his stance, telling the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee he’d instructed border agents not to separate families unless “the situation at the time requires it.”The policy reversal also appeared to contribute to the stalling of a Texas bill backed by state Republicans that would have allowed immigrant detention centers to become licensed child-care facilities.Family separation has been happening sporadically for the past few years, as it did to Ana and Cesar. Ana’s attorney, Clarissa Bejarano, who works with detainees in the women’s immigrant detention center T. Don Hutto in Taylor, Texas, says that in an average month about three mothers there are separated from their kids, particularly during months with a high amount of border crossings. A recent Women’s Refugee Commission report revealed that the separations “are arbitrary and require no justification or documentation and do not involve any child welfare expertise.”Refugees hoping to enter the country were not happy when they heard about Kelly’s plan to make family separation official policy.“[Families] were terrified, they were angry,” said Ariel Prado, project manager for the CARA Pro Bono Project, which provides legal services to immigrant families being held in Southwest Texas Residential Center. “For some they knew it was a total violation of their human rights, and others were just scared.”A spokesperson for U.S. Customs and Border Protection said she could not find information about Ana and Cesar’s separation in the CBP database; Bejarano confirmed that CBP had separated the pair at the border. The CBP spokesperson echoed Kelly’s claim that DHS keeps families intact whenever possible.“The DHS policy has not changed,” public affairs specialist Yolanda Choates said in an emailed statement. “DHS doesn’t separate mothers from children at the border except under extenuating circumstances, such as illness or injury, or protection of the child/children.”One lesser-known shift in immigration enforcement that could put families at higher risk of deportation involves a change in the so-called credible fear test, the first phase in the asylum process, during which an officer interviews the applicant to determine if he or she is eligible to solicit asylum in a U.S. court.In February, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services released new standards that raise the bar for passing the test. Previously asylum officers were directed to pass an applicant if there was a “significant possibility” of qualifying for asylum, but that wording has now been removed from the USCIS “lesson plan” for asylum officers. Advocates fear the change could cause officers to turn away asylum seekers who are, in fact, eligible for protection.“This places a lot of power in the asylum officer,” Prado said. “The moms we’re seeing are pretty heavily traumatized, and add to that the trauma of being detained and then putting them in front of a perfect stranger and asking them to talk about some of the most extreme things that have happened to them.” In other words, asylum seekers may not reveal traumatic details in initial interviews, and since agents are no longer directed to give them the benefit of the doubt, eligible asylum seekers may now get turned away.That isn’t what happened to Ana and Cesar, but Ana did spend two months in detention before being reunited with her son.“I thought I wasn’t going to get to see my mother again,” said Cesar, who was released along with his mother in late March after Ana’s attorney petitioned Immigration and Customs Enforcement to reunite the family. “I was so happy to see her again.”Cesar leans on Ana in their cousin’s Austin apartment, where the pair are staying during their court proceedings.“I’ll go to every court date,” Ana said, “and just pray they let us stay.”

There has been a dramatic drop in the number of families arriving at the U.S. border, though the exact reasons for that remain unclear. The Department of Homeland Security reported in early April a 93 percent drop in the number of children and parents caught trying to enter the U.S. illegally.There are currently just 305 inmates in South Texas’ two family immigrant detention centers, according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement; the centers have enough beds for 3,600, and they were almost constantly filled as recently as 2015. In March, 12,000 people were apprehended at the border — a 63 percent drop from last March, according to Customs and Border Protection.The dip in arrivals means more families are enduring the threat of extreme harm at home — many are fleeing ongoing gang violence in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala — because they’re worried things would be even worse in the U.S., says Denise Gilman, director of the University of Texas’ Immigration Law Clinic.“The situation on the ground in Central America hasn’t changed at all,” Gilman said. “People are still suffering greatly as a result of widespread violence and human rights violations. So the lower number of individuals seeking asylum at the border is just an indicator of how dramatic the cruelty is in the steps that have been announced [by the U.S.].”Even though America is legally bound to allow asylum seekers who appear at the border into the country, immigration agents began flatly turning some away after the election, according to advocates who work on the border. Nicole Ramos, project coordinator for the Border Rights Project, which works with asylum seekers in Tijuana, Mexico, said she frequently encounters asylum seekers who were denied entry into the U.S.The news of such rejections, and of Trump’s refugee bans, prompted many prospective asylum seekers to stop even trying to enter the country because they believe they, too, will be turned away. (A refugee ban could not stop the U.S. from accepting asylum seekers who arrive at the border.)“Many are confused because of the talk about the refugee ban, about whether it applies to asylum seekers,” Ramos said. “I’ve heard confusion from asylum seekers and also staff at different shelters.”Families have been distraught over the separation of mothers and children, a policy DHS Secretary John Kelly announced last month, saying he planned to implement it on a large scale in order to deter families from attempting to enter the country. But he later reversed his stance, telling the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee he’d instructed border agents not to separate families unless “the situation at the time requires it.”The policy reversal also appeared to contribute to the stalling of a Texas bill backed by state Republicans that would have allowed immigrant detention centers to become licensed child-care facilities.Family separation has been happening sporadically for the past few years, as it did to Ana and Cesar. Ana’s attorney, Clarissa Bejarano, who works with detainees in the women’s immigrant detention center T. Don Hutto in Taylor, Texas, says that in an average month about three mothers there are separated from their kids, particularly during months with a high amount of border crossings. A recent Women’s Refugee Commission report revealed that the separations “are arbitrary and require no justification or documentation and do not involve any child welfare expertise.”Refugees hoping to enter the country were not happy when they heard about Kelly’s plan to make family separation official policy.“[Families] were terrified, they were angry,” said Ariel Prado, project manager for the CARA Pro Bono Project, which provides legal services to immigrant families being held in Southwest Texas Residential Center. “For some they knew it was a total violation of their human rights, and others were just scared.”A spokesperson for U.S. Customs and Border Protection said she could not find information about Ana and Cesar’s separation in the CBP database; Bejarano confirmed that CBP had separated the pair at the border. The CBP spokesperson echoed Kelly’s claim that DHS keeps families intact whenever possible.“The DHS policy has not changed,” public affairs specialist Yolanda Choates said in an emailed statement. “DHS doesn’t separate mothers from children at the border except under extenuating circumstances, such as illness or injury, or protection of the child/children.”One lesser-known shift in immigration enforcement that could put families at higher risk of deportation involves a change in the so-called credible fear test, the first phase in the asylum process, during which an officer interviews the applicant to determine if he or she is eligible to solicit asylum in a U.S. court.In February, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services released new standards that raise the bar for passing the test. Previously asylum officers were directed to pass an applicant if there was a “significant possibility” of qualifying for asylum, but that wording has now been removed from the USCIS “lesson plan” for asylum officers. Advocates fear the change could cause officers to turn away asylum seekers who are, in fact, eligible for protection.“This places a lot of power in the asylum officer,” Prado said. “The moms we’re seeing are pretty heavily traumatized, and add to that the trauma of being detained and then putting them in front of a perfect stranger and asking them to talk about some of the most extreme things that have happened to them.” In other words, asylum seekers may not reveal traumatic details in initial interviews, and since agents are no longer directed to give them the benefit of the doubt, eligible asylum seekers may now get turned away.That isn’t what happened to Ana and Cesar, but Ana did spend two months in detention before being reunited with her son.“I thought I wasn’t going to get to see my mother again,” said Cesar, who was released along with his mother in late March after Ana’s attorney petitioned Immigration and Customs Enforcement to reunite the family. “I was so happy to see her again.”Cesar leans on Ana in their cousin’s Austin apartment, where the pair are staying during their court proceedings.“I’ll go to every court date,” Ana said, “and just pray they let us stay.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement