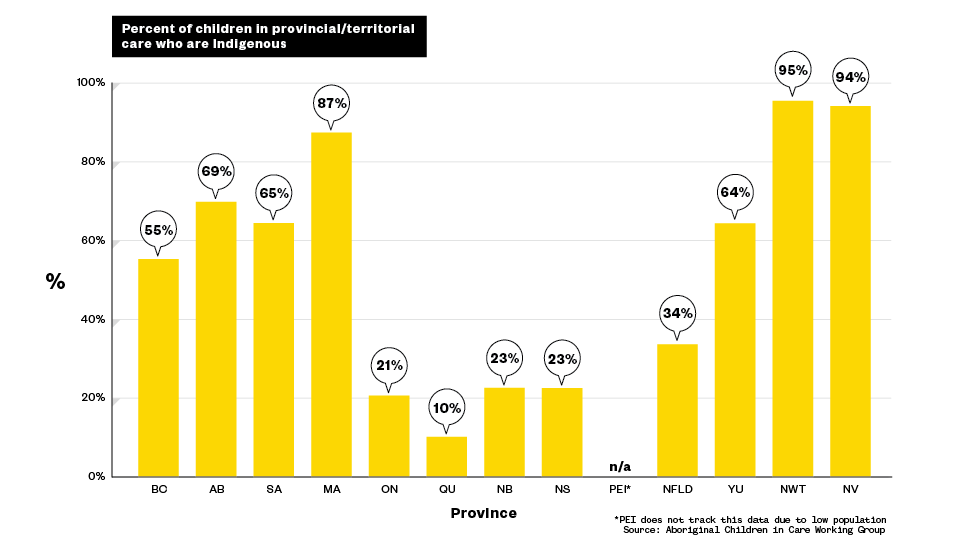

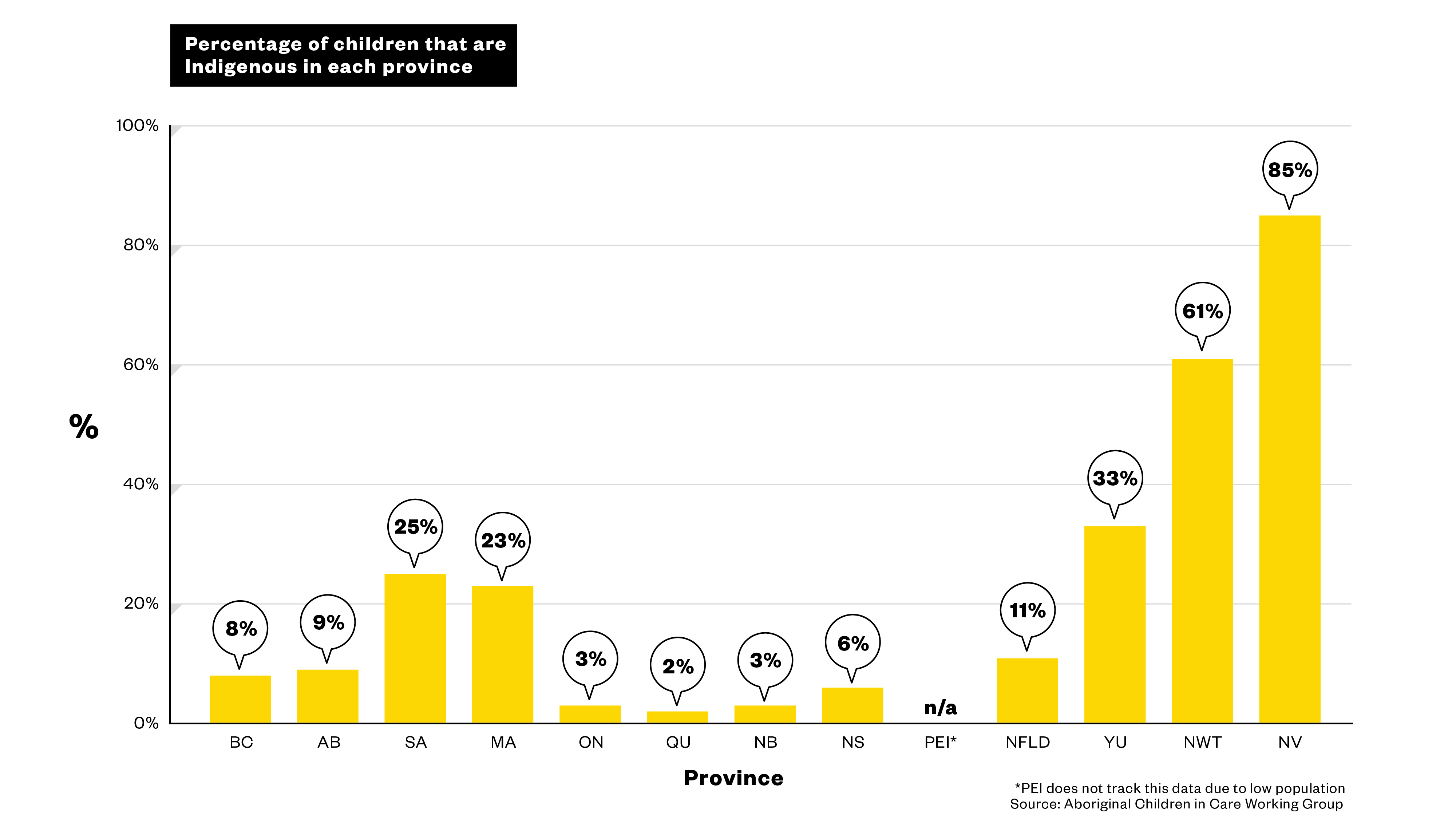

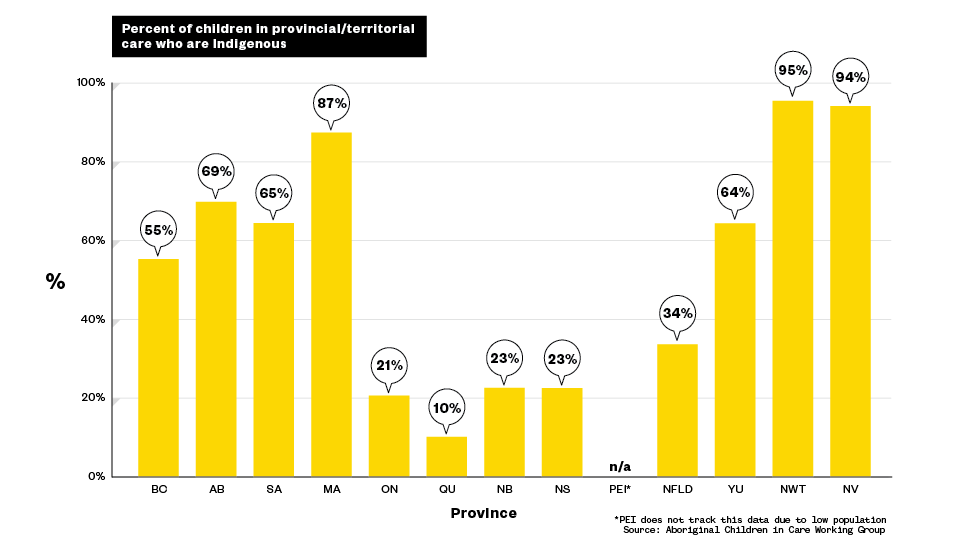

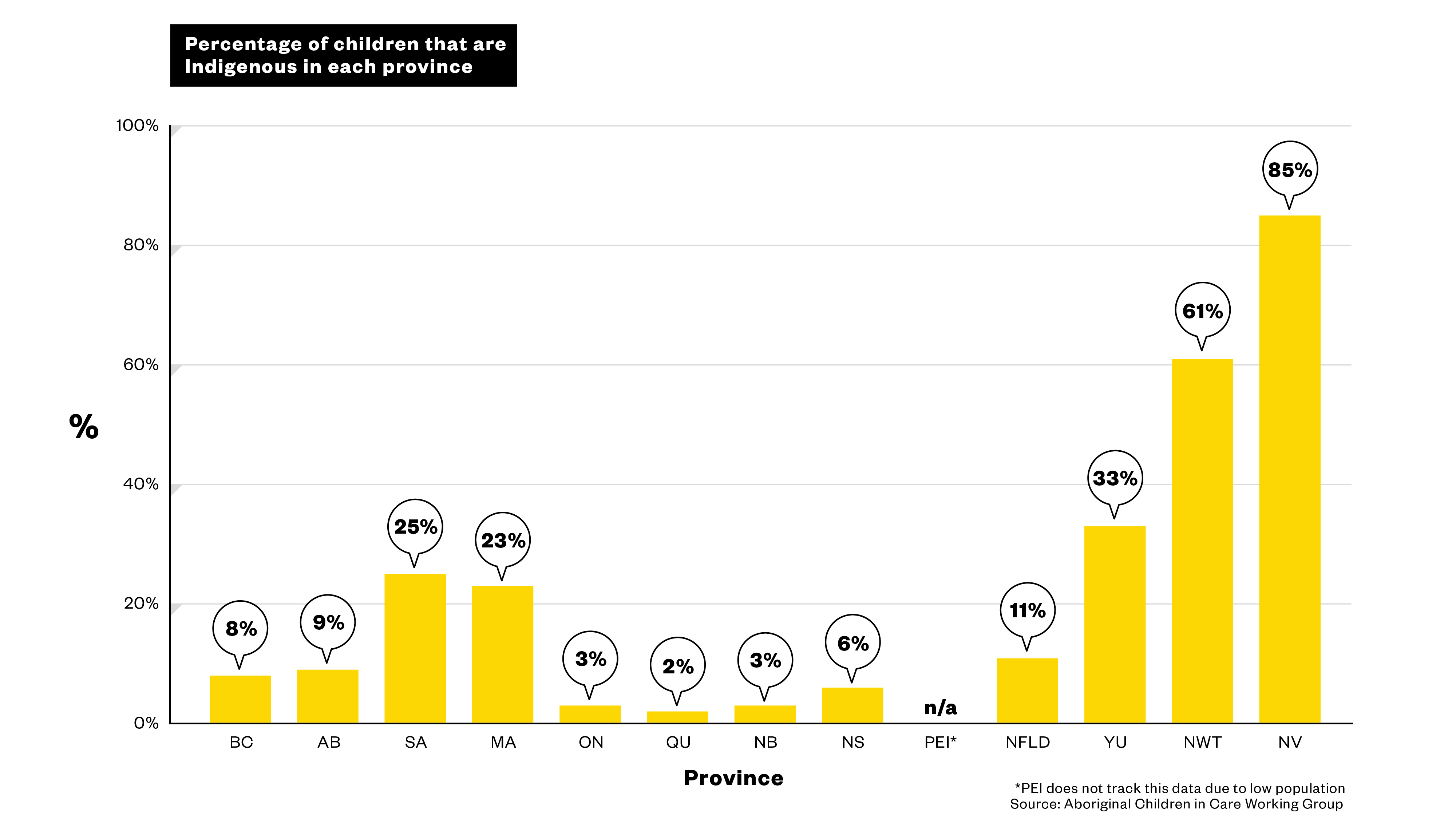

Barbara Edwards remembers when her daughter, Raven, moved back into her house in Peterborough, Ontario with her new baby boy.He was her first grandson, a tiny little bundle everyone wanted to be near. All the women in the household — Edwards, Raven, and Raven’s grandmother — took turns bathing him all day. It’s all they wanted to do.“The boy was never put down for any length of time,” recalled Edwards.In 2013, she said, the Children’s Aid Society showed up at their door with a list of allegations claiming that Raven had been neglecting her newborn. At the root of it all are longstanding systemic issues that many say continue to go ignored — from intergenerational trauma caused by government policies seeking to assimilate Indigenous peoples, to unequal funding that lays the groundwork for child removal.Child welfare, the term used to describe services designed to protect a child from abuse and neglect, is a complicated system in Canada that it is overseen by provincial governments, each with their own set of rules, and administered by local agencies, each with their own approaches.Although the federal government has jurisdiction on First Nations reserves, a child that is removed from a community becomes the responsibility of the provincial government.The process is trickier in remote areas, when regional child welfare agencies step in. If they determine that a child must be moved from their home or community, a representative from the band council must sign off — that process, however, is not universal and there are instances where the band is not consulted.Exactly why so many Indigenous children end up in state custody is a big question.Indigenous people account for just over 4 percent of the overall population in Canada, but represent 48 percent of all children and youth in the care of social services. These statistics vary from province to province, with Indigenous children making up 87 percent of children in care in Manitoba.

At the root of it all are longstanding systemic issues that many say continue to go ignored — from intergenerational trauma caused by government policies seeking to assimilate Indigenous peoples, to unequal funding that lays the groundwork for child removal.Child welfare, the term used to describe services designed to protect a child from abuse and neglect, is a complicated system in Canada that it is overseen by provincial governments, each with their own set of rules, and administered by local agencies, each with their own approaches.Although the federal government has jurisdiction on First Nations reserves, a child that is removed from a community becomes the responsibility of the provincial government.The process is trickier in remote areas, when regional child welfare agencies step in. If they determine that a child must be moved from their home or community, a representative from the band council must sign off — that process, however, is not universal and there are instances where the band is not consulted.Exactly why so many Indigenous children end up in state custody is a big question.Indigenous people account for just over 4 percent of the overall population in Canada, but represent 48 percent of all children and youth in the care of social services. These statistics vary from province to province, with Indigenous children making up 87 percent of children in care in Manitoba.

Vandna Sinha, an assistant professor in the school of social work at McGill University, has researched extensively the impact social policies have on children’s access to social services, with much of her recent work focusing on Indigenous families.“The child welfare system is set up, in theory, to first of all investigate situations in which children might be exposed to a risk of harm,” she said. That includes physical and sexual abuse, she noted, but more than anything else chronic risks like poverty, mental health and substance abuse issues.“When we look at First Nations families, because of patterns that have to do with colonialism, which I would see as ongoing, those families have had a lot of harm and trauma inflicted on them that have given them a lot of stresses that other families don’t necessarily encounter in the same way.”The adoption of thousands of Indigenous children to non-Indigenous families during a time known as the Sixties Scoop perpetuated the damage.Barbara Edwards herself was a victim of the Sixties Scoop. She was taken away at birth from her mother, who had to fight to get her back on more than one occasion from social services.

Vandna Sinha, an assistant professor in the school of social work at McGill University, has researched extensively the impact social policies have on children’s access to social services, with much of her recent work focusing on Indigenous families.“The child welfare system is set up, in theory, to first of all investigate situations in which children might be exposed to a risk of harm,” she said. That includes physical and sexual abuse, she noted, but more than anything else chronic risks like poverty, mental health and substance abuse issues.“When we look at First Nations families, because of patterns that have to do with colonialism, which I would see as ongoing, those families have had a lot of harm and trauma inflicted on them that have given them a lot of stresses that other families don’t necessarily encounter in the same way.”The adoption of thousands of Indigenous children to non-Indigenous families during a time known as the Sixties Scoop perpetuated the damage.Barbara Edwards herself was a victim of the Sixties Scoop. She was taken away at birth from her mother, who had to fight to get her back on more than one occasion from social services. While attending Shoreham Public School in Toronto in the mid 1970s, Edwards remembers being spanked in front of the class for sitting in the wrong seat.“My mom went in to complain,” Edwards told VICE News.“The vice principal told my mom the only thing a squaw was good for was breeding and fucking.”Later, Edwards would have to fight for her Indian status after her grandmother married a non-Native man and lost her’s — a policy under the Indian Act that has since been reformed.She’s faced racism surrounding her First Nations heritage her entire life.“In Canada it’s still possible to get a bachelors’ of social work degree without taking any courses on Aboriginal peoples.”That’s a point Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, uses to illustrate how little things are changing.“[The government] has not learned from the residential schools and Sixties Scoop … What they need to do is reform the department. And create space for experts on the ground to implement and reform child welfare,” said Blackstock.VICE News reached out to the Children’s Aid Society of Ontario with a list of questions regarding their process when investigating an Indigenous child’s welfare. We were directed to their report of the residential services review panel, which made findings and recommendations on how to improve the experiences of young people living in residential care. A short section on Indigenous children outlines their over-representation within the system and notes that they should have access to more culturally appropriate programs. It does not offer suggestions to help keep children in their own homes or communities.“Our government is ensuring that First Nations children and families have access to the services and supports they need,” Bennett said.Various Indigenous representatives who spoke to VICE News said that if communities were able to retain more authority over the welfare of their children, that would be a solution.

While attending Shoreham Public School in Toronto in the mid 1970s, Edwards remembers being spanked in front of the class for sitting in the wrong seat.“My mom went in to complain,” Edwards told VICE News.“The vice principal told my mom the only thing a squaw was good for was breeding and fucking.”Later, Edwards would have to fight for her Indian status after her grandmother married a non-Native man and lost her’s — a policy under the Indian Act that has since been reformed.She’s faced racism surrounding her First Nations heritage her entire life.“In Canada it’s still possible to get a bachelors’ of social work degree without taking any courses on Aboriginal peoples.”That’s a point Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, uses to illustrate how little things are changing.“[The government] has not learned from the residential schools and Sixties Scoop … What they need to do is reform the department. And create space for experts on the ground to implement and reform child welfare,” said Blackstock.VICE News reached out to the Children’s Aid Society of Ontario with a list of questions regarding their process when investigating an Indigenous child’s welfare. We were directed to their report of the residential services review panel, which made findings and recommendations on how to improve the experiences of young people living in residential care. A short section on Indigenous children outlines their over-representation within the system and notes that they should have access to more culturally appropriate programs. It does not offer suggestions to help keep children in their own homes or communities.“Our government is ensuring that First Nations children and families have access to the services and supports they need,” Bennett said.Various Indigenous representatives who spoke to VICE News said that if communities were able to retain more authority over the welfare of their children, that would be a solution. Sinha believes that, rather than having a system that is built to remove children, there needs to be a system that helps families who are reeling from intergenerational trauma with family and community-based social services.“The impact of being a caregiver who is trying to provide for your child and doing the best they can, then there’s someone who is sent in to investigate whether your child has been harmed or exposed to harm — that’s a very different thing then someone coming to see if there are supports that you need if there are ways that they could help you,” Sinha added.She noted that while there is legislation in most jurisdictions that make accommodations for Indigenous communities “it’s not a system that was built by them or built for them.”***Raven said the aid worker showed up and entered the house without notice, while she, her mother and sister were still asleep. Ontario allows child protection workers to enter a home and remove a child if they have a warrant; they don’t need a warrant to enter if they believe a child is in need of immediate protection and any delay would put them at risk.“She went on to tell her supervisor that I was on drugs and that my child was screaming like he was in pain, and that I wouldn’t wake up,” Raven recalled.“We were then called into a meeting with my social worker her supervisor…I was deemed unsafe and told I couldn’t have any unsupervised contact with my child.”After a series of heated meetings, Raven said she requested another worker that worked with her to get her deemed a safe parent.“I took parenting classes and graduated and [was] certified. I made it to every doctor’s appointment and it took over two years for them to deem me safe and able to be unsupervised with my son,” said Raven whose oldest son is now 4.“We should never have been with them as long as we were,” Barbara Edwards said.“After they found out that he was fine and treated well and loved they should have closed the case.”

Sinha believes that, rather than having a system that is built to remove children, there needs to be a system that helps families who are reeling from intergenerational trauma with family and community-based social services.“The impact of being a caregiver who is trying to provide for your child and doing the best they can, then there’s someone who is sent in to investigate whether your child has been harmed or exposed to harm — that’s a very different thing then someone coming to see if there are supports that you need if there are ways that they could help you,” Sinha added.She noted that while there is legislation in most jurisdictions that make accommodations for Indigenous communities “it’s not a system that was built by them or built for them.”***Raven said the aid worker showed up and entered the house without notice, while she, her mother and sister were still asleep. Ontario allows child protection workers to enter a home and remove a child if they have a warrant; they don’t need a warrant to enter if they believe a child is in need of immediate protection and any delay would put them at risk.“She went on to tell her supervisor that I was on drugs and that my child was screaming like he was in pain, and that I wouldn’t wake up,” Raven recalled.“We were then called into a meeting with my social worker her supervisor…I was deemed unsafe and told I couldn’t have any unsupervised contact with my child.”After a series of heated meetings, Raven said she requested another worker that worked with her to get her deemed a safe parent.“I took parenting classes and graduated and [was] certified. I made it to every doctor’s appointment and it took over two years for them to deem me safe and able to be unsupervised with my son,” said Raven whose oldest son is now 4.“We should never have been with them as long as we were,” Barbara Edwards said.“After they found out that he was fine and treated well and loved they should have closed the case.”

Advertisement

“They were told I was doing drugs and drinking,” Raven said in an interview.“I don’t do drugs and I hadn’t had an alcoholic beverage since 2012 before I found out I was pregnant with my son.”According to Raven, what followed was a two year battle to earn the right to be with her child unsupervised, a right that was only granted after Raven was able to find a children’s aid worker who would work with her to settle the investigation.“They made me feel like I was an animal and like I had no right to be a parent,” Raven told VICE News. “I do believe that me being Native set off an alarm with them.”Raven never lost custody of her son. But her story is illustrative of the ways in which First Nations families across Canada have felt targeted by child welfare agencies investigating their abilities as parents, a pattern that stretches over decades.VICE News reached out to the aid society’s Peterborough office, but it declined to comment, saying it cannot disclose information about a closed case without a court order.It’s a country-wide issue. This year, in Ontario, outrage and pleas for reform followed the deaths of First Nations youth living in group homes thousands of kilometres away from home. Newfoundland just announced it is holding an inquiry into the treatment of Innu children in child protection services.“I do believe that me being Native set off an alarm with them.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

She points to a “systemic pattern” in the child welfare system that was not built on good faith and did not treat Indigenous communities as partners.It extends back over a century, to the country’s former residential school policy, which forcibly removed children from their homes and sent them to boarding schools, where they endured physical, emotional and sexual abuse. Thousands of children died within these institutions, and those who survived carried the deep, destructive scars home, which have reverberated through generations.“The vice principal told my mom the only thing a squaw was good for was breeding and fucking.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Blackstock said the child welfare system in Canada does not account for the intergenerational impacts of residential schools. And it has yet to comply with four orders from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, which found that the federal government was discriminating against Indigenous children by spending 38 percent less on child welfare on reserves than off reserves. The consequences of that are dramatic: The tribunal found that by holding these families to the same child welfare standards as those that have more funding for these services, more children from reserves end up being removed from their families.“Canada’s on going underfunding of child welfare is a continuance of the residential school programs,” argued Blackstock, who said most of the Canadian public is in the dark about why First Nations children are taken away from their families.“I don’t make excuses for families who don’t make changes when they have the opportunity to change,” she said. “But when we’re talking about a state giving them less because of their race, then that’s hugely problematic. I’m not sure Canadians have clued into how egregious that truly is,” said Blackstock.Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett has previously said she accepts the tribunal’s finding and would work to fix inequality in the system — but it has received four non-compliance orders from the tribunal.“Canada’s on going underfunding of child welfare is a continuance of the residential school programs.”

Advertisement

“The only way we’re going to stop our children being lost to Crown wards is through First Nations’ jurisdiction,” Gord Peters, Deputy Grand Chief of the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians, told VICE news.“That’s the only solution that’s left on the table to be able to change things. Otherwise [Ontario Children’s Aid Services] continues this industry with our children.”This year, four children from reserves in northern Ontario died while in provincial care, away from their communities because they were not able to access the health services they needed at home.“Our kids shouldn’t be sent 1,000 miles away for them to be able to support these services so they aren’t disconnected from their families,” Alvin Fiddler, Grand Chief of Nishnawbe Aski Nation told the Toronto Star earlier this year.“There needs to be far more investments in mental health and addictions treatment that’s culturally based on reserve,” agreed Blackstock.“It’s not a system that was built by them or built for them.”

Advertisement