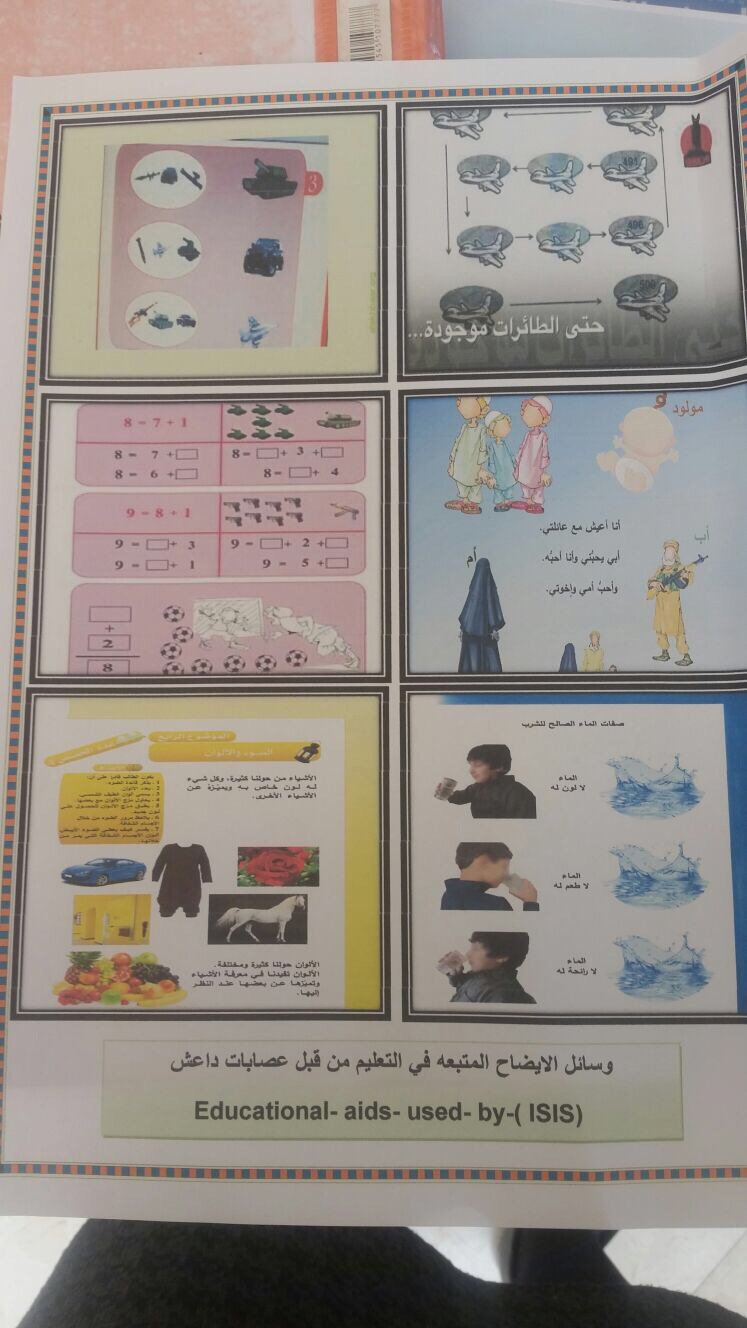

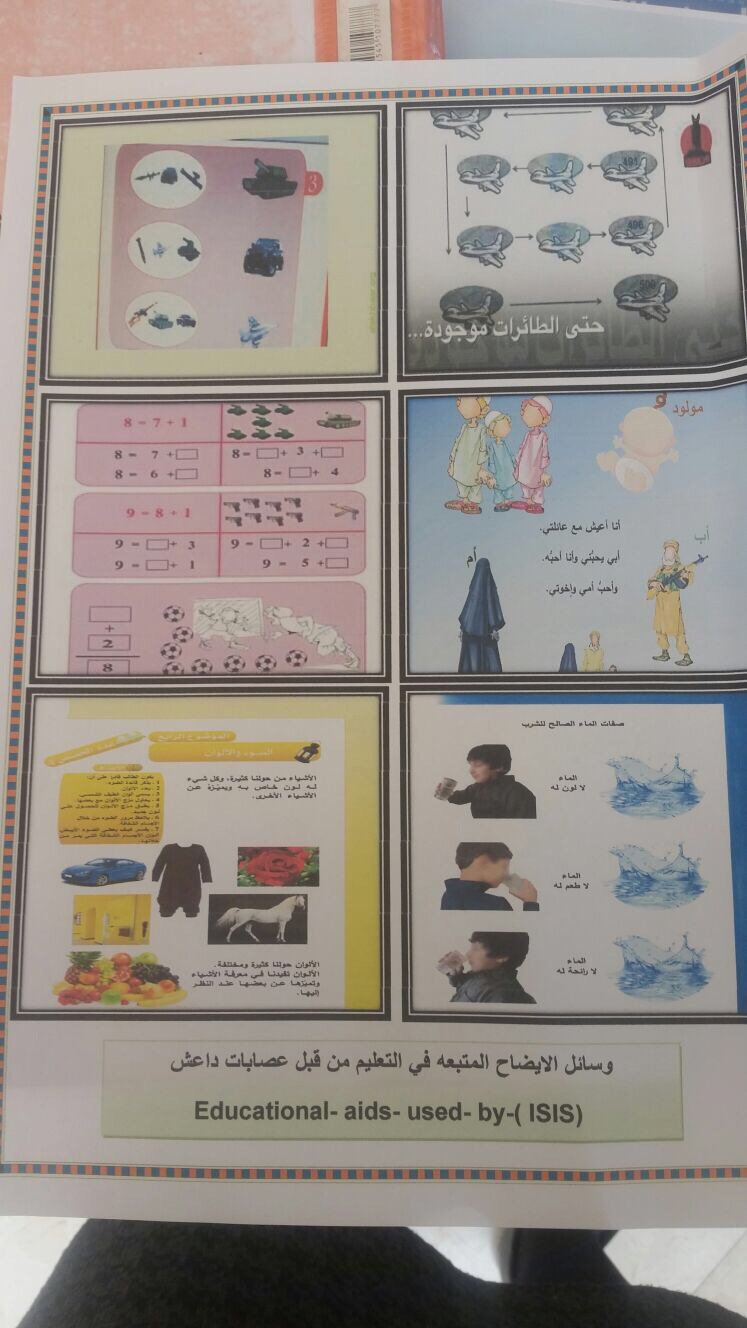

As it fights to rid itself of the Islamic State, the Iraqi government is turning to Canada for help in dealing with the deradicalization of its citizens, VICE News has learned.“Iraqi authorities are very interested in what we’re doing in Canada, with the centre,” Deparice-Okomba told VICE News. “They sought out our expertise in terms of training and psychosocial interventions.” Vast swaths of Iraq have been under IS control since the civil war began in 2014, but government officials predict Iraqi armed forces will soon be able to push the so-called caliphate out of the country.“In Iraq the defeat [of ISIS] is sure, it’s definite. We’ll finish the job in a very short time,” Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi said last month. “It’s within reach, within the next few weeks.”As the military fights to regain the northern city of Mosul — ISIS’s last major stronghold in the country — the Iraqi government has started to plan how to deal with Iraqis were lived under, or fought for, IS.“Deradicalization is not a collective process, it requires national reconciliation, a conversation about what happened,” he said. “You have to understand the motivations, the psychological and social contexts.”The Montreal centre was created in 2015, in response to a wave of at least 25 Quebecers who left or tried to leave the country to join militant groups. Specific numbers are hard to come by, but according to a 2016 report, an estimated 180 Canadians are believed to have joined the ranks of terrorist organisations abroad since 2014, most of them teaming up with ISIS.The Montreal centre, which operates independently from government and police, has so far fielded nearly 1,500 cases, conducting interventions and providing information about different forms of radicalization. Only the cases that pose an immediate risk to public security — 24 so far — are reported to police.“Iraq is currently divided in two, with two educational systems. One is managed by the legal government and the other by the Islamic state,” he told VICE News. “Children [under the ISIS system] learn to count using pictures of gun cartridges. There’s hate speech, there are children who have been indoctrinated.”Updating pedagogical tools to give kids better critical thinking abilities will make them more resilient to ISIS propaganda, Deparice-Okomb said. His team also recommends the implementation of a new history curriculum that “recognizes the contributions of different ethnic and religious minorities” and could as such prevent future radicalisation.

Vast swaths of Iraq have been under IS control since the civil war began in 2014, but government officials predict Iraqi armed forces will soon be able to push the so-called caliphate out of the country.“In Iraq the defeat [of ISIS] is sure, it’s definite. We’ll finish the job in a very short time,” Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi said last month. “It’s within reach, within the next few weeks.”As the military fights to regain the northern city of Mosul — ISIS’s last major stronghold in the country — the Iraqi government has started to plan how to deal with Iraqis were lived under, or fought for, IS.“Deradicalization is not a collective process, it requires national reconciliation, a conversation about what happened,” he said. “You have to understand the motivations, the psychological and social contexts.”The Montreal centre was created in 2015, in response to a wave of at least 25 Quebecers who left or tried to leave the country to join militant groups. Specific numbers are hard to come by, but according to a 2016 report, an estimated 180 Canadians are believed to have joined the ranks of terrorist organisations abroad since 2014, most of them teaming up with ISIS.The Montreal centre, which operates independently from government and police, has so far fielded nearly 1,500 cases, conducting interventions and providing information about different forms of radicalization. Only the cases that pose an immediate risk to public security — 24 so far — are reported to police.“Iraq is currently divided in two, with two educational systems. One is managed by the legal government and the other by the Islamic state,” he told VICE News. “Children [under the ISIS system] learn to count using pictures of gun cartridges. There’s hate speech, there are children who have been indoctrinated.”Updating pedagogical tools to give kids better critical thinking abilities will make them more resilient to ISIS propaganda, Deparice-Okomb said. His team also recommends the implementation of a new history curriculum that “recognizes the contributions of different ethnic and religious minorities” and could as such prevent future radicalisation. Deparice-Okomba also addressed with Iraqi officials the many Canadians who have travelled to the region to fight with Islamic State militants.“We have families in Montreal, in Quebec whose children are in Syria,” he said. Though none of these Canadians are currently detained in Iraq, he expects some will eventually end up languishing in the Iraqi justice system. “I think the Canadian government needs to better collaborate with the Iraqi government on these issues, in anticipating the end of the war, so that we can have extradition policies and a plan to take charge of the Canadians who are over there,” he said. “We have to be proactive.”Deparice-Okomba can’t say if or when his team could return to Iraq. “The next step will be to see if the centre will accompany [the government] through this process but I’d say there is interest,” he said. “The centre will likely be a key player.”

Deparice-Okomba also addressed with Iraqi officials the many Canadians who have travelled to the region to fight with Islamic State militants.“We have families in Montreal, in Quebec whose children are in Syria,” he said. Though none of these Canadians are currently detained in Iraq, he expects some will eventually end up languishing in the Iraqi justice system. “I think the Canadian government needs to better collaborate with the Iraqi government on these issues, in anticipating the end of the war, so that we can have extradition policies and a plan to take charge of the Canadians who are over there,” he said. “We have to be proactive.”Deparice-Okomba can’t say if or when his team could return to Iraq. “The next step will be to see if the centre will accompany [the government] through this process but I’d say there is interest,” he said. “The centre will likely be a key player.”

Last week, Herman Deparice-Okomba, the director of Montreal’s Centre for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence, travelled to the Middle Eastern country to meet with government officials to discuss what to do with the populations who could soon be back under the control of Iraq’s central government.“Iraqi authorities are very interested in what we’re doing in Canada, with the centre.”

Advertisement

Hundreds of thousands of citizens have spent the last few years under IS rule, subjected to various forms of indoctrination and trauma. These citizens, Deparice-Okomba said, will require a massive amount of psychological and pedagogical resources.There are different degrees of radicalization, he explains. As such, militant IS fighters will not require the same approach as those who were reluctantly forced to live under the caliphate’s governance. The country will therefore have to be ready to offer a great deal of individualized care, which will require training and preparing more front-line staff — psychologists, social workers, teachers — for the heavy task of deconstructing ideology.Hundreds of thousands of citizens have spent the last few years under IS rule, subjected to various forms of indoctrination and trauma.

Advertisement

The first of its kind, the radicalization prevention centre has been recognized across the globe as an example to follow, and other governments often contact Deparice-Okomba for guidance with their own radicalization issues. In February 2016, former UN secretary general Ban Ki-Moon visited the centre and praised its role in the prevention of terrorism.Deparice-Okomba also told representatives from the Iraqi Ministry of Education and Ministry of Higher Learning and Scientific Research they should consider a massive reform of the Iraqi school system.“Children [under the ISIS system] learn to count using pictures of gun cartridges.”

Advertisement