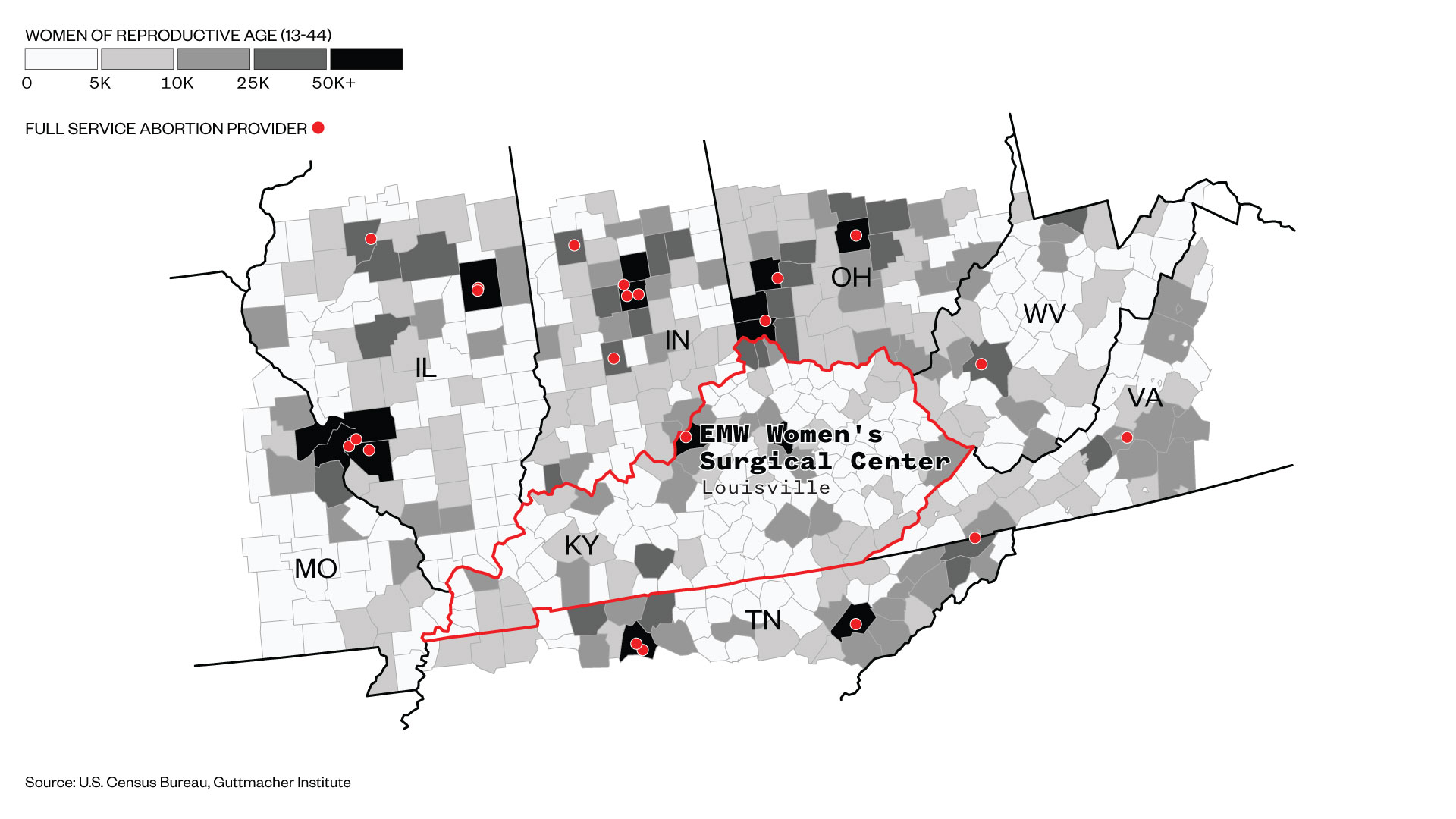

Earlier this year, Kentucky’s Republican Gov. Matt Bevin moved to close the state’s last remaining abortion clinic, the EMW Women’s Surgical Center in Louisville. Kentucky’s second-to-last clinic, run by the same providers in Lexington, had run up against new licensing requirements and was forced to close in January. Now, the Louisville clinic and the governor are in a legal battle to decide whether Kentucky will become the first state in the U.S. with no abortion provider at all.

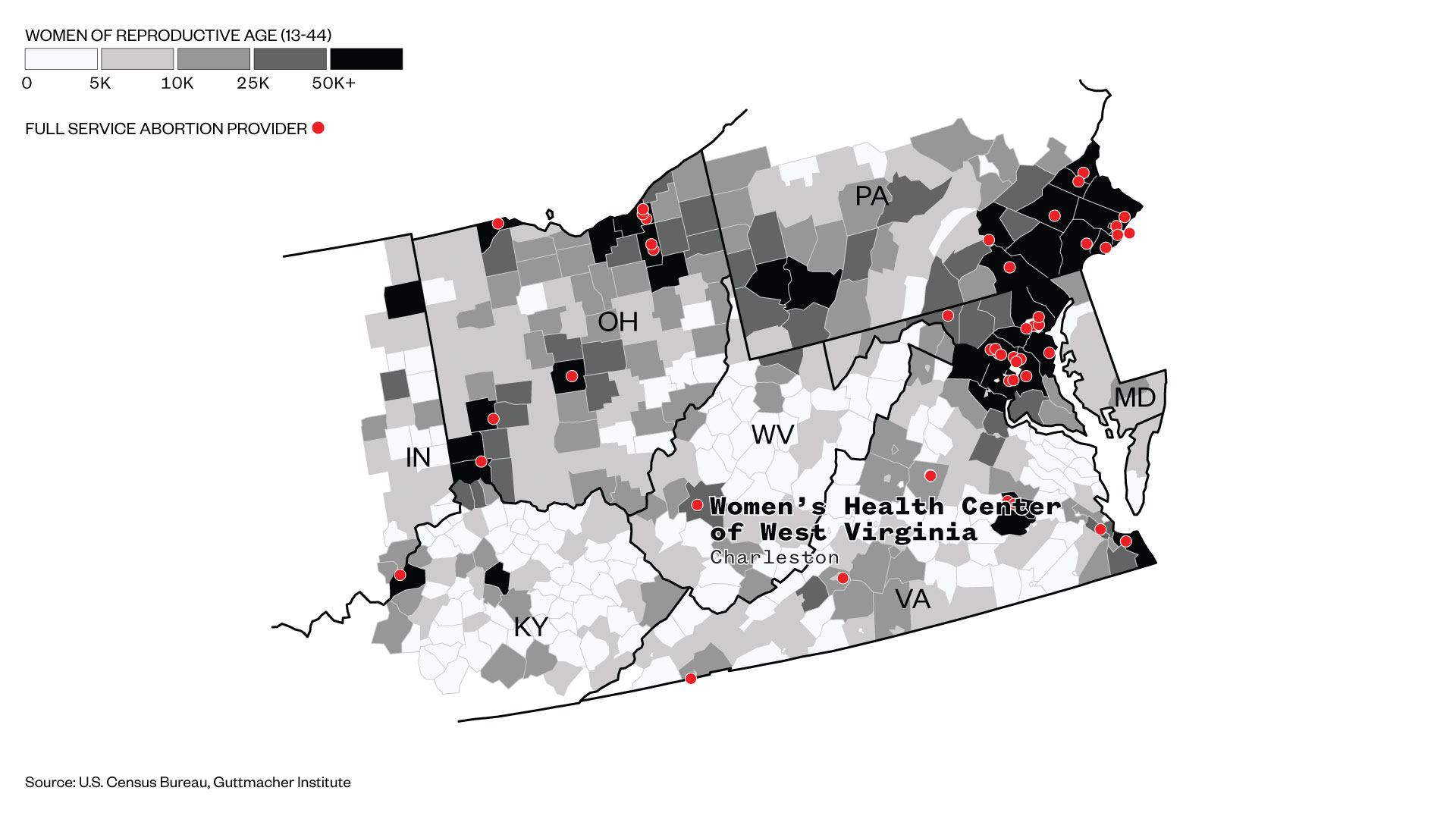

Women in Kentucky aren’t the only ones running out of options. Across the country, the number of abortion clinics has been declining for years, and after another clinic closed in West Virginia in January, seven states have just one abortion provider left. (An eighth, Arkansas, has only one full-service provider offering both medication and surgical abortions.)

Demand for abortion in the United States is at a record low level as more women use contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancies, but an estimated 926,000 abortions were performed in 2014. And women have ever fewer options for care as lawmakers — who cannot ban abortion outright — push ever more restrictions aimed at forcing providers to close.

Closures affect more than abortion care; each of these facilities offers a range of women’s health and other medical services, including pap smears and birth control. And even though it’s sometimes possible to get an abortion elsewhere (from a private physician or in a hospital or by driving across state lines), access for most women is limited to the nearest clinic.

Directors and physicians at the last clinics in these seven states spoke with VICE News to tell us the history of their practices and describe the challenges they continue to face. Interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Kentucky

Ernest Marshall, physician

EMW Women’s Surgical Center of Louisville

“I trained to do abortion during my residency. Afterward, one of my professors and my partner and I decided to open our own clinic, in 1981. We’ve always been full-fledged OB-GYN physicians. At the time, there were three or four other providers in Louisville. Then in 1989 we opened a satellite clinic in Lexington.

My partner and I, Dr. Sam Eubanks, we operated the two clinics together until he passed away in December 2013. We were dedicated to this work and to our patients. The other providers just voluntarily closed over the years. My two clinics have been the only ones in the state for a fairly long time, at least 10 or 15 years.

Around 1998, they created the abortion clinic license. But when we opened the facility in Lexington, we didn’t qualify for a license because we were just a small doctor’s office. And we operated as a doctor’s office until Gov. Bevin decided that because we did abortions we would need an abortion license. So we went to court, and the courts agreed with him. So then we applied for a license, but they didn’t want to give us one. They control both ends of the situation.

“Every day my patients say they appreciate what we do for them. That’s what people don’t get to hear.”

What they used as a smokescreen to deny the license were the transfer agreements. We had the proper transfer agreements, but they didn’t approve of them. In Kentucky you need a transfer agreement with a hospital and an ambulance.

We really never had any operating troubles from the government [before]; that only began with Bevin. For the first time in Kentucky, the Republicans [control] the House, the Senate, and the governorship. And things changed dramatically. We’ve always had protesters and anti-abortion people, but we’ve never had such political opposition.

In the first week, they passed and signed two anti-abortion laws. [The first banned abortion after 20 weeks and the second required doctors to narrate ultrasounds.] Bevin is a right-to-life governor, and Kentucky is a right-to-life state, but there have always been plenty of pro-choice people in Kentucky. It’s never been smooth sailing. We were always threatened with obstructive laws, but we were never threatened with the possibility of closure.

We filed a federal lawsuit against the governor last month. The trial is set for September. We have a temporary restraining order that allows us to continue operating the Louisville clinic until then.

We’ve remained open because of dedication — dedication to the cause. It’s been part of my life’s work to work on women’s reproductive freedom. And I will keep doing it. Every day my patients say they appreciate what we do for them. That’s what people don’t get to hear.”

West Virginia

Sharon Lewis, executive director

Women’s Health Center of West Virginia

“The Women’s Health Center of West Virginia opened in 1976. I started working here in 1988 as a case manager for a parenting program. At that time we were basically dealing with the same kinds of issues that we have today, but maybe not as many of them. We were just trying to make sure that we had the staffing that was required to comply with all of the regulations.

In 2002, the Legislature passed the so-called Women’s Right To Know Act, which required that a biased counseling script had to be delivered to every patient by a licensed medical professional. So we had to hire somebody. And that’s the kind of thing the anti-choice people advocate for, because it costs us additional money.

Only about 20 percent of our patients come here for abortion care. We get patients from Ohio and Kentucky, not so much Virginia. Lately we’ve been seeing greater numbers of Kentucky residents. The majority of our services are what we call in-clinic procedures; the trend is to get away from calling it surgery. It’s not really surgery. We’re not cutting people.

We have a neighbor, a crisis pregnancy center, that changed their name to Women’s Choice to confuse patients who intend to come here and end up in their doorway. They have a marquee out front that says, “Considering abortion? Free pregnancy test.”

Until this year there were two facilities in the state that advertised abortion care. I believe there are private doctors who do certain procedures for friends and family. But they’re not called abortions.

“Only about 20 percent of our patients come here for abortion care.”

Kanawha Surgicenter just closed [in January], but it wasn’t about restrictions. The Kanawha physician just relocated to California and closed his practice. As far as them closing, it just imposes a greater responsibility on us to provide access. It just makes our job a little bigger to make sure that access is maintained.

This year, the Legislature added additional restrictions for access to abortions for minors. They were tweaking the law over the last session and took out the clause that would have allowed a psychiatrist or psychologist to provide a waiver to minors. Now the only waiver is judicial, despite the fact that last year only four minors used a waiver. To them it’s not even about practicality; it’s about their philosophical opposition to abortion. It’s not a rational decision. It’s a solution looking for a problem.”

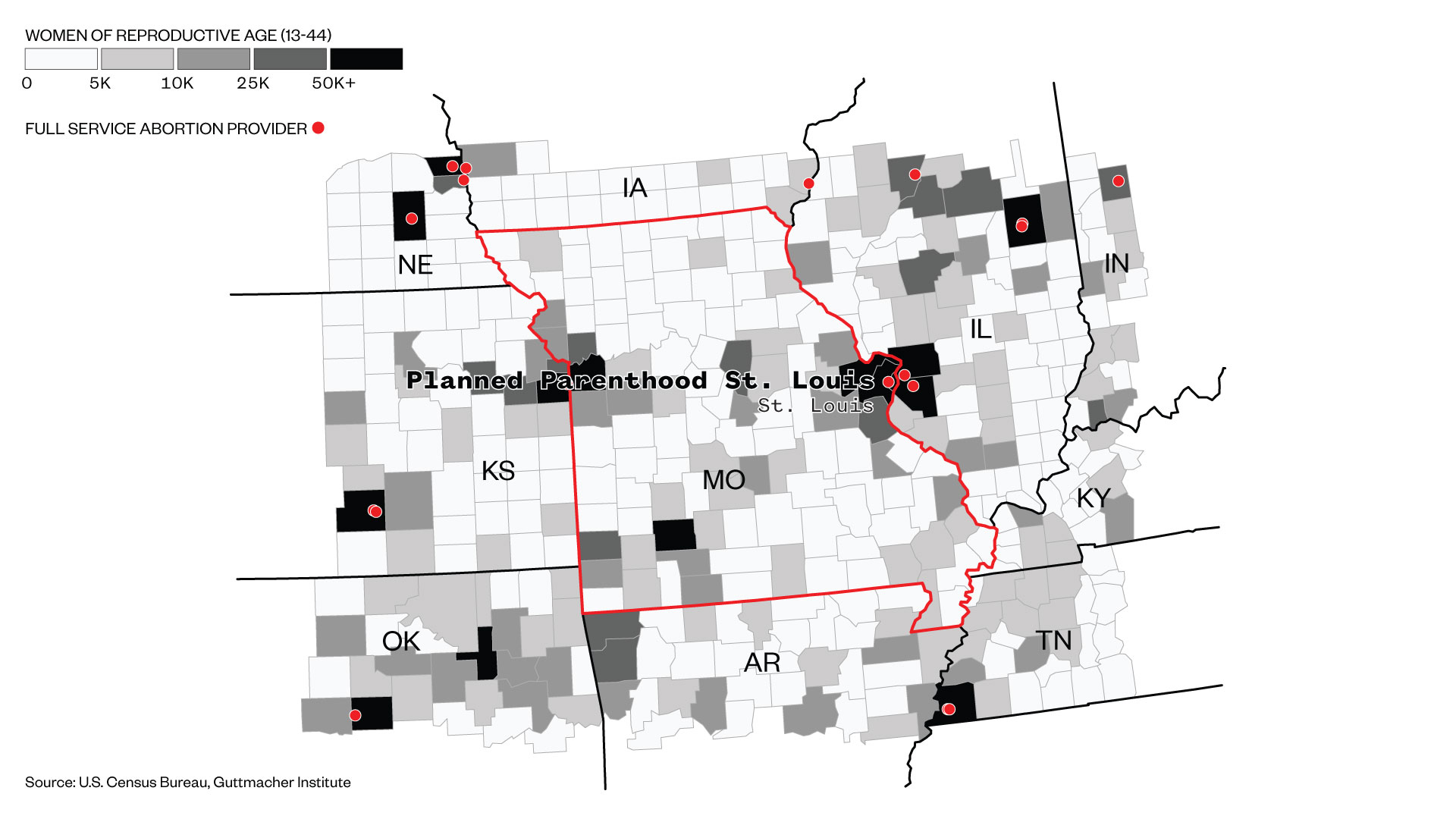

Missouri

Mary Kogut, president and CEO

Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri

“There are 12 Planned Parenthood–affiliated centers that provide care in Missouri but only one that can do abortions. The Reproductive Health Services of Planned Parenthood St. Louis Region is the only state-licensed abortion center in the entire state.

At one time there were many other abortion providers in the state. In the 1980s, I know there were a number of other private providers, as well as Reproductive Health Services, an independent, nonprofit abortion provider. Reproductive Health Services was one of the oldest centers in the Midwest — they started very quickly after Roe v. Wade.

When it was clear that they needed some assistance to continue, Planned Parenthood came and took them over. We weren’t providing abortion care in Missouri at all up until that time. We opened on May 1, 1996, in a facility that was three blocks away from where we are now.

When we moved into our new building in 1998, we designed it according to the ambulatory regulations so that we could provide care according to the law. We worked with a state architect to ensure that all of our rooms were the proper sizes, that they had the right ventilation systems, that they had everything we needed in order [to comply]. We get inspected each year, and these are the types of things they look at.

We serve about 40,000 patients, primarily from Missouri and Illinois, but we also see patients from about 10 surrounding states. Less than 10 percent of our patients come for abortion-related care. About a third of our abortion procedures are medication abortions, but that percentage is going up every year.

Off and on, our affiliate in Great Plains has provided abortion services in their Columbia facility. In federal court last year, they challenged the Missouri laws that require our centers to be licensed ambulatory surgical centers and to have hospital admitting privileges. And last week we got a preliminary injunction against those requirements, so it’s possible that the Great Plains location could start providing abortion services again.

The state has filed an appeal and a stay against the preliminary injunction, so we’re just waiting to see what happens. But our one-provider status could be changing in Missouri.”

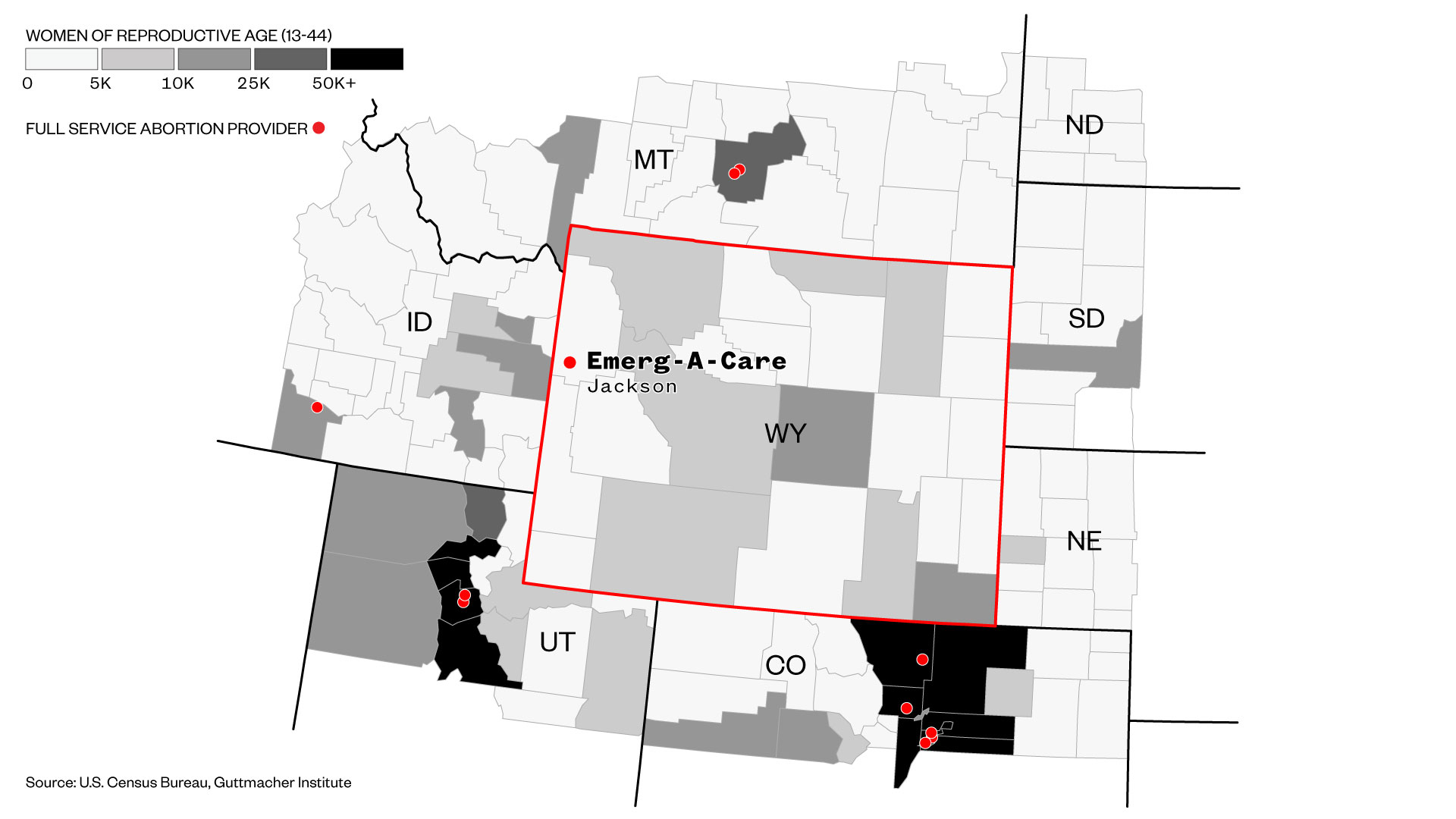

Wyoming

Brent Blue, physician and director

Emerg-A-Care, Jackson

“We’re the only provider in state that acknowledges we do terminations. I’ve heard that there are two others in our county that do medical abortions, but they don’t acknowledge it publicly, and they only offer it to their patients. But if they do more than five abortions a year, I’d be surprised. Still, I think it’s weird that we’re considered the only provider in the state when we’re not.

I started practicing medicine here in July of 1982. I was looking for a small town in the mountains and kind of lucked into Jackson Hole. We opened in 1990 under the name Emerg-A-Care; before that it was just Brent Blue, MD. Emerg-A-Care is just a family practice disguised as urgent care. I wanted tourists to know that they could just walk in.

In 1994, we had a bombing. Some guy was traveling across the country and bombing various facilities. We had a tremendous amount of smoke damage, but it was at night, so no one was hurt. We were closed down for several weeks, but we had a lot of community support, even from people who are anti-choice. Wyoming is a ‘Live and let live’ state — people may disagree, but they generally don’t tell their neighbor what to do.

The entire state of Wyoming only has 500,000 people, so we’re not talking about a huge population density here. But a woman shouldn’t have to drive 400 miles to get a termination.

We have a lot of people that come from eastern Idaho, which is very Mormon, and I think some women there are afraid to talk to their providers. So they come to us.

“A woman shouldn’t have to drive 400 miles to get a termination.”

Wyoming just passed two truly stupid laws this year. They go into effect July 1. One prohibits selling of fetal tissue, which is a response to a fraudulent claim to begin with. The second law is that patients have to be offered the opportunity to look at the ultrasound, but we do ultrasounds anyway, so if they want to look, all they have to do is turn their head to the right. It’s a law that has no teeth, and there’s no way to enforce it. It won’t change one thing for us.

Less than one-half of 1 percent of our services are for abortions. The majority of our termination services are medical, probably 80 percent. Most termination clinics offer a wide variety of family planning services, so I don’t think it’s fair to call them abortion clinics. We’re really providing women’s health care.

I think a lot of physicians don’t want the hassle, or maybe they’re afraid. There are negative aspects, too. There are people who won’t come to our family practice because we provide termination services. And that’s one of the things I’m willing to accept.”

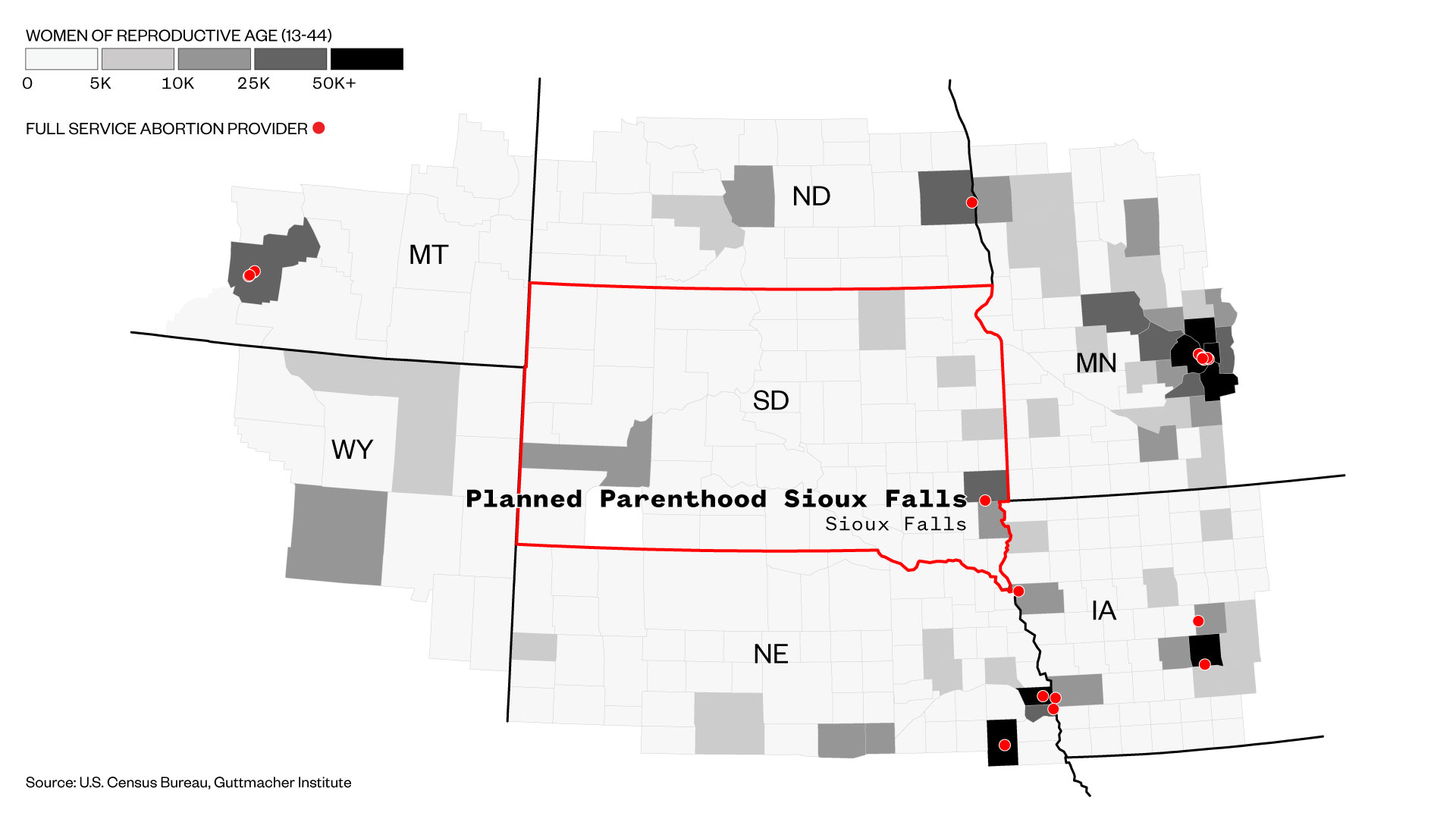

South Dakota

Sarah Stoesz, president and CEO

Planned Parenthood Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota

“For a long time, there was a doctor who provided illegal abortions in Rapid City, South Dakota. He was known throughout the upper Midwest; I heard stories of planeloads of women coming from the Twin Cities on the days that he was providing abortions. And there was always a tacit understanding among the townspeople, so he was left alone and continued his practice for quite a long time, until he retired.

Dr. Buck Williams began to perform abortions at his clinic in Sioux Falls around 1981, and for a while he was the only provider in the state. Planned Parenthood wasn’t in South Dakota at that point, but he came to us and asked if we would take over his practice in 1989. The Sioux Falls Planned Parenthood has been the only abortion provider in the state ever since.

When we moved out of our old facility, it was taken over by the Alpha Center, a really aggressively right-wing crisis-pregnancy center led by a woman named Leslee Unruh. She worked really hard to confuse women who were accustomed to going to our old location. There was a sign on the Alpha Center door that said something like, “Need help planning your parenthood?” I used to periodically get phone calls from women that had mistakenly thought they were going to Planned Parenthood and went to the Alpha Center instead.

Harold Cassidy, a lawyer in New Jersey, struck up a relationship with Unruh and kind of adopted South Dakota. I think he recognized that it was a state that was highly religious, very white, and somewhat easy to manipulate politically. He’s written some of the really dreadful pieces of legislation and has been behind many of the unsuccessful attempts to ban abortion in the state altogether.

In 2006, the Legislature passed a total and complete ban on abortion and the governor signed it into law. So we chose to challenge that law at the ballot box. We were convinced that even though the state was electing all these conservative legislators, and that the majority of people in South Dakota say they are pro-life, that they wouldn’t want a total ban on abortion. We won by 12 points.

“None of our physicians are from Sioux Falls; we’ve never been able to hire a doctor from the area.”

Two years later, they came back with a ban on abortions except in cases of rape, incest, and the health of the woman. Again we challenged it on the ballot, and we won that one, too. I really think people in South Dakota don’t want to ban abortion.

None of our physicians are from Sioux Falls; we’ve never been able to hire a doctor from the area. So we have four doctors who fly in on rotation. It’s a tremendous waste of resources and it’s very expensive to keep this practice up. I’ve met a few doctors who have moved to the state in the last couple of years, so I’m not giving up.

I do feel very supported by the voters in South Dakota, even though the politicians aren’t supportive of us. That first doctor who openly and illegally performed abortions for some time, that’s in the libertarian tradition of South Dakota. Live and let live. Unfortunately that is not the predominant view in the Legislature.”

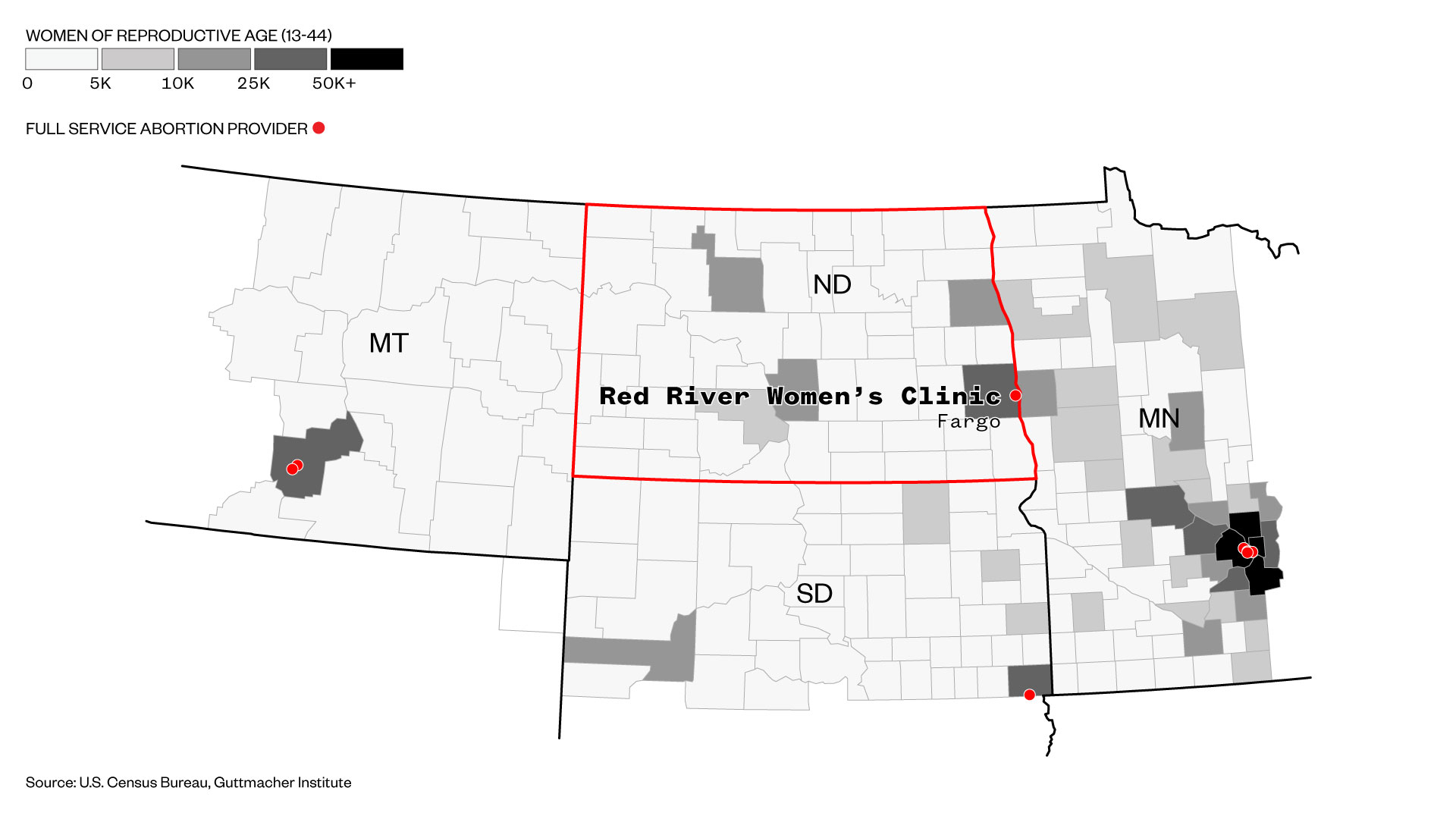

North Dakota

Tammi Kromenaker, clinic director and owner

Red River Women’s Clinic, Fargo

“After Roe v. Wade, there were two doctors providing abortion care in North Dakota. There was one in Grand Forks and one in Jamestown, about an hour east and an hour west of Fargo. As those doctors were getting close to retirement, they approached Jane Bovard, who was very well known in the state for helping women find places to get an abortion in Minneapolis or neighboring states. The doctors asked her to open a clinic in Fargo.

So in the fall of 1981, she helped bring the Women’s Health Organization to North Dakota. The Women’s Health Organization was the largest independent abortion provider and had eight clinics across the country at the time. Jane met the woman who was running that organization, Susan Hill, and told her to come to Fargo. They opened the first abortion clinic together in North Dakota.

Jane had protesters at her home — she was always being threatened. She’d be calling 911 while her husband loaded the shotgun. She put up with a lot, both personally and professionally. Then by 1991, both those doctors who had been providing abortions passed away or retired, and the Women’s Health Organization became the only provider.

I was hired at Fargo Women’s Health in November of 1993, working one or two days per week as a patient educator, meeting with women, and talking about their abortion decision. Dr. George Miks was the primary physician, and he had worked with Jane for a long time. After awhile they said, ‘Hey, we can do this better,’ and decided to open their own place. That was Red River Clinic. I went along with them.

We opened our doors for patients on July 31, 1998. Both clinics existed for about two and a half years. Both were in Fargo and they were about six blocks apart from each other. There was some confusion: ‘Oh there’s two places. How do I determine which one to go to?’ When we opened Red River Women’s Clinic, the Women’s Health Organization dropped their fees by $100.

The abortion numbers in North Dakota have always remained pretty steady, at about 25 abortions per week. On the first day we opened, three women walked in. One woman was too far along, but we provided two abortions that day. The scales slowly started tipping; we started seeing more and more patients. I truly think we can attribute that to Jane and Dr. George Miks. I would answer the phone and hear, “Is this Jane’s clinic? Is this Dr. Miks’ clinic?” They wanted to send their patients to the providers they knew.

Then one day, very unexpectedly, a patient called us and told us the other clinic had closed. So we became the only abortion provider in February 2001. North Dakota isn’t very populated — we’re only seeing patients one day per week, on Wednesdays. We see about 20 to 25 patients per week.”

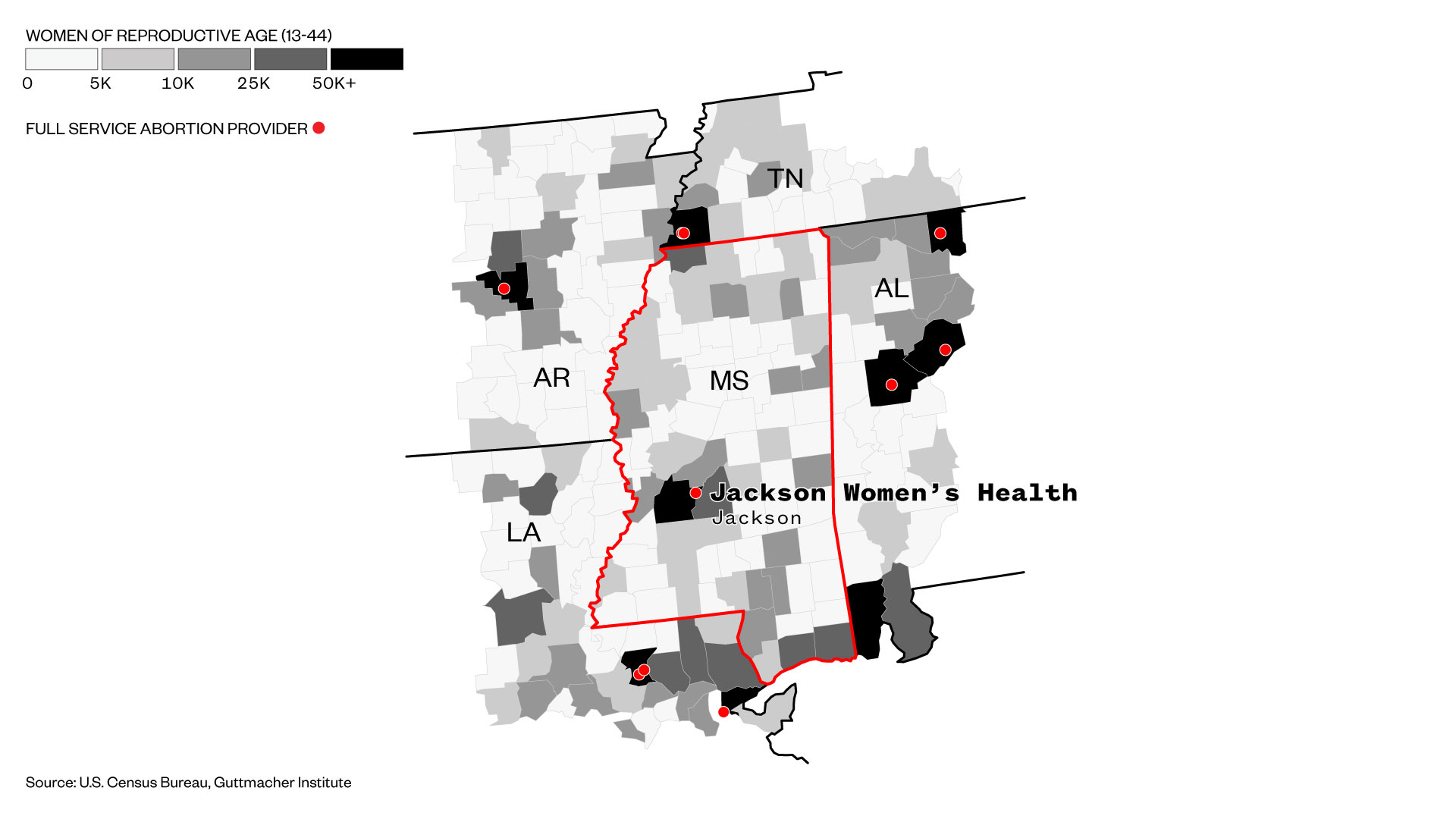

Mississippi

Shannon Brewer, clinic director

Jackson Women’s Health

“At one point there were at least a dozen clinics in Mississippi, but we’ve been the only one for 11 years. Mississippi has always been a pretty hostile environment, but when I first started, it wasn’t as hostile at this facility. The protesters were targeting a different clinic in Jackson. But once that one closed, we became the only target left. We’ve been burglarized. Our cameras and our generator have been vandalized.

I started working at Jackson Women’s Health in 2000. I had just had my youngest son, and my aunt at the time was the director here and they were just looking for some help. I had never dealt with anything pertaining to women’s health care or abortion. But once I was here, I started listening to her and just watching what was going on, and it grew from there. I initially came in to work part-time, and 17 years later, I’m still here. My aunt’s still here too. She’s a counselor.

The building wasn’t always hot pink. The new owner who came in 2010 decided to paint it that color. Before that, it was more of a beige color. When I heard we were going to paint it pink, I was like, ‘You cannot be serious.’ But once it was done, we got so much positive feedback from it, I kind of looked at it differently. I wasn’t worried that painting it pink would make us stand out more. We already stand out here.

We have around 10 protesters outside every day. I just walk right in, they talk to me every morning. I’ve heard the same thing for 17 years, so it’s like, ‘Come up with something new for me!’ It’s always the same people.

We see about 30 to 40 patients per week. About 90 percent of our patients are here for abortion services. We do both medical and surgical abortions — it’s pretty even. I’d say about 50-50.

The closest I was to being worried we’d have to close was when [the state Legislature] added the hospital admitting privileges in 2012. None of the local hospitals would give our doctors admitting privileges, even though they are qualified OB-GYNs. We were down to the last day when the judge made the ruling. We thought we wouldn’t be open the following day.

I don’t know why we’ve managed to stay around. We just do everything by the book and we just try to stay on top of everything they’re trying to get passed. We don’t just lie back and let them do what they want, to play these games with these TRAP laws. We stand up for each and every thing they try to do to us. And so far we’re doing OK because we’re still here.

I became the clinic director in 2010. I just try to go with the flow every day and remain as calm as possible. I think it’s crucial that we remain here for women, they have nowhere else to go. They can go to neighboring states, but why should they have to? Each state should be able to provide this service for women.”

Watch VICE News Tonight’s coverage on the last clinics standing:

Alexa Liautaud and Louisa Oreskes contributed research.