Photographs by Maddie McGarvey for VICE News

The opioid epidemic that killed an estimated 53,000 people last year is now a national emergency, but for years in small towns across the country the emergency has been a painfully local one. In these communities, public officials and private citizens are doing their best to curb fatal overdoses and get help for their neighbors, often with few resources and little experience.

The burden tends to fall first on police officers, and in two very similar towns at the center of the crisis — where drug overdose rates are more than twice the national average — cops decided to do things differently this year. In Washington Court House, Ohio, a police chief fed up with unceasing overdose calls is treating addiction as a crime. Ninety miles south, on the other side of the Ohio River in Alexandria, Kentucky, law enforcement is for the first time approaching addiction as a disease. Their choices may be different, but both departments have the same goal: to get people using opioids including heroin and its deadlier cousins, fentanyl and carfentanil, into treatment and on the path to recovery.

VICE News visited both towns to learn how these policies are working from the people living through them.

“Nobody knows what to do with this. Everybody’s grasping at straws to curb it, to cure it.” Brian Hottinger, police chief

Earlier this year, Brian Hottinger responded to what had become a familiar scene. A woman and her boyfriend using heroin had overdosed at home. Unable to wake them, the woman’s 5-year-old daughter dialed random numbers until she reached a family friend, who called 911. Paramedics revived them both, but less than two weeks later, the woman overdosed again.

Hottinger was deeply frustrated that he and his department of 20 officers couldn’t do more. Eleven people in town have died of overdoses this year, and paramedics administered naloxone, a lifesaving overdose-reversal medication, 249 times through the end of August. The town didn’t budget for the thousands it has now spent on naloxone, which Hottinger estimates costs them about $100 a dose.

“We found that we were responding to calls and it was the same people over and over,” he said. “We were treading water just like everybody else in Ohio, with no great answer and no way to resolve this.”

Last September, Ohio introduced a Good Samaritan law that, with some exceptions, stops cops from arresting anyone who overdoses or who calls 911 on behalf of someone overdosing. It’s supposed to save lives by encouraging people to call for help, but Hottinger thinks the measure goes too far in the direction of condoning drug use. A 29-year veteran of the police department, he wants to be able to enforce drug laws.

“In the mind of every police officer I know, possession of heroin is illegal, period,” he said. Reviving an overdose victim is only a short-term fix — without stiffer penalties for using or some way to get people away from drugs, he doesn’t see how things can change.

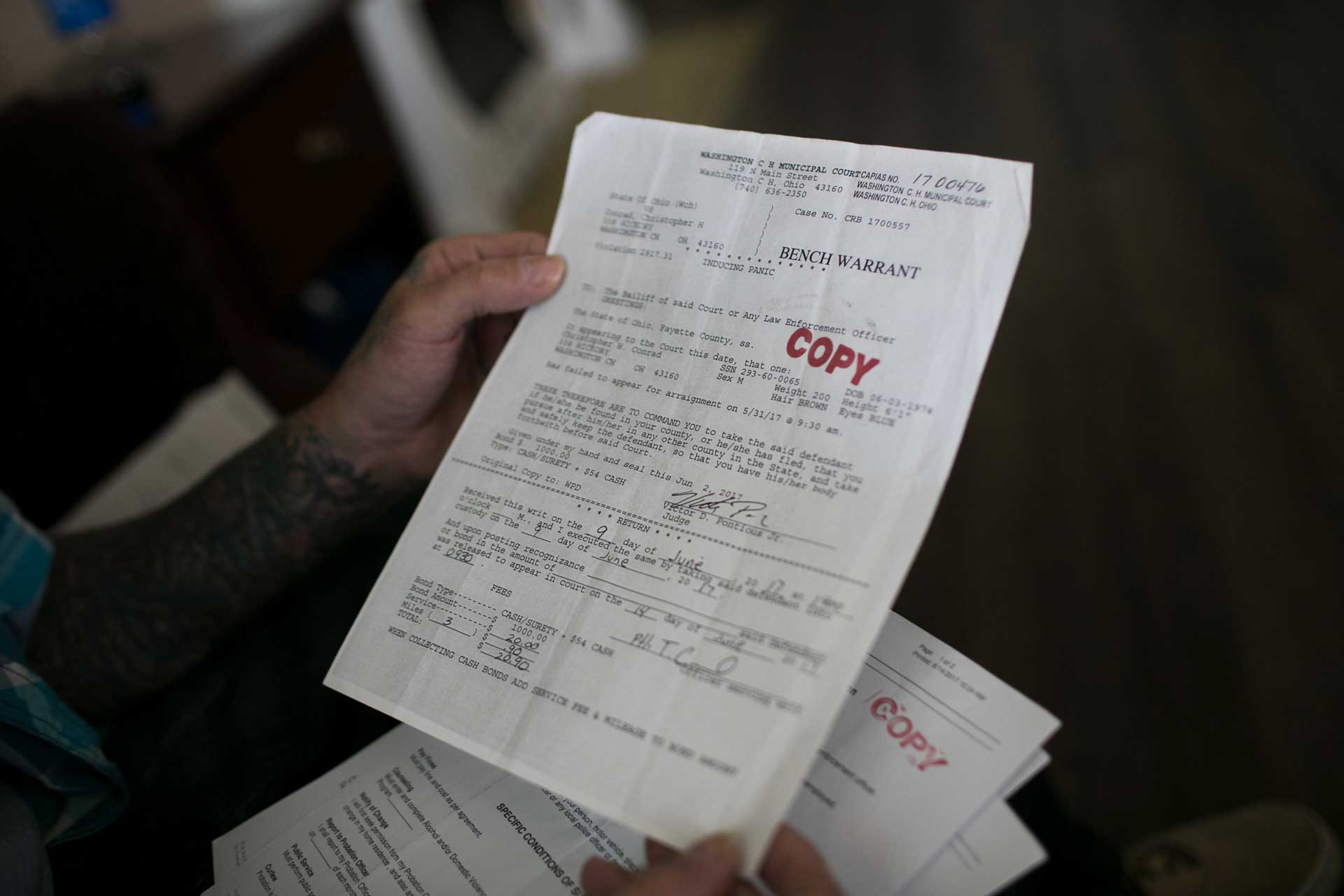

Since possession charges were off the table, one of his officers searched for a minor offense they could use to charge overdose victims instead. The idea was to force drug users in front of a judge and into court-ordered treatment. They settled on “inducing panic,” a misdemeanor that carries a fine of up to $1,000 and 180 days in jail; the charge was previously used against a group of teenagers who were driving around town brandishing plastic guns.

Washington C.H. (the local abbreviation) isn’t the only place in Ohio taking a harder-line approach to addiction. In neighboring Chillicothe, officers are using a similar charge of disorderly intoxication to arrest overdose victims. And in Middletown, a city councilman recently floated the idea of a three-strikes overdose policy: Paramedics would revive the same person only twice; after that, they’d be on their own.

Officers in Washington C.H. have plenty of discretion over when to invoke “inducing panic,” but since February, 43 people have been charged — some more than once. If they’re convicted, a judge will mandate a treatment program. If they complete the program, the charges are dismissed.

“We’re not after jail time. We’re not after fines. The goal is to get them into the court system and into treatment,” Hottinger said. So far, no one has served any jail time for inducing panic; 17 people have been convicted and are headed to treatment instead. (Six cases were dismissed, 10 people were sent to a diversion program, three people failed to appear in court, and the rest of the cases are still pending.)

Like many police departments around the country, Hottinger’s welcomes anyone who walks in seeking help. But that hasn’t happened, and he sees the misdemeanor charge as the best way to make sure they get it.

“There is no easy answer for this; all we’re trying to do is save one person at a time,” said city attorney Mark Pitstick, who prosecutes these cases. “Is it right or wrong? I don’t know. Everybody has a right to criticize.”

“Police officers are not wired to be social workers. When we are slaved to a portable radio and a dispatch center, we cannot honestly and effectively help people in emotional crisis.” Mike Ward, police chief

The drive from Washington C.H. to Alexandria is almost entirely flat. For 70 miles down Interstate 71, there’s nothing but low crops and clear skies, save for the Kings Island roller coasters that briefly cut the horizon. After about an hour, the Cincinnati skyline and the Ohio River come into view. On the other side, curving green hills mark the start of Kentucky.

Alexandria and Washington C.H. are typical of the small, rural towns scattered across the country. Both make up less than 10 square miles with a population of around 10,000 and are more than 90 percent white. Only about a third of the residents in both towns have a college degree. Household incomes in Alexandria are modest but somewhat higher; you can see it in the two-story brick townhouses and new businesses popping up along Route 27.

There were 35 overdoses in Alexandria through July — almost as many as there were in all of 2016 — six of them fatal. Kentucky has a Good Samaritan law too, and rather than find a new way to punish overdose victims, last year Police Chief Mike Ward made his department the first in the state to hire a full-time police social worker. He convinced the City Council to give him the extra funds.

“We’re a 17-person police department and we were hit hard,” he said. “We had to do something.”

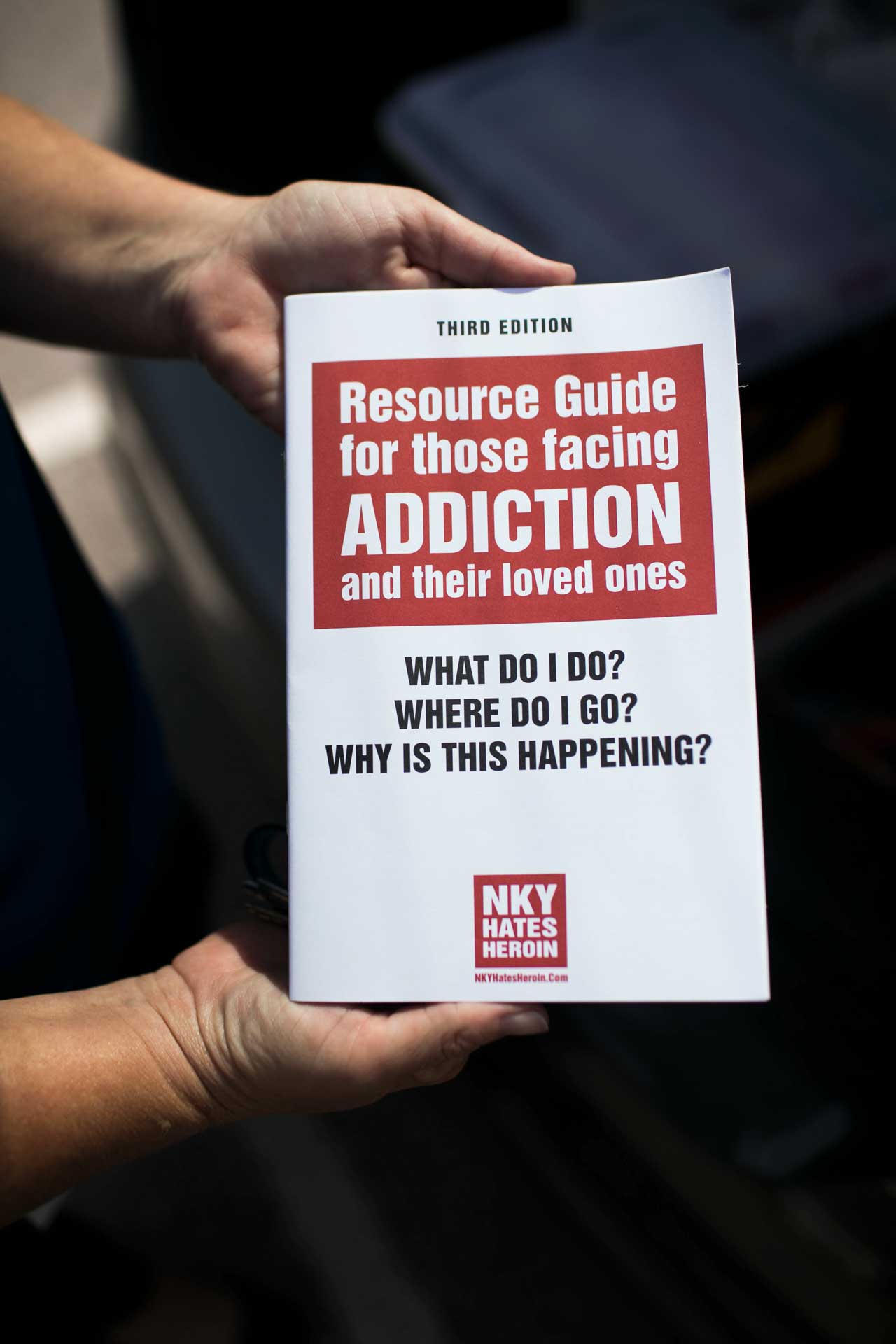

His hire was Kelly Pompilio, who holds a master’s degree in social work and spent 12 years with the state’s Cabinet for Health and Family Services. In her first few months on the job, she helped put together a version of a national program that supports local police departments dealing with people addicted to opioids. They called their initiative the Alexandria ACTS Angel Program.

Pompilio responds to every overdose in Alexandria, either on the scene or the day after, and makes it clear she’s a social worker, not a cop. (She also reaches out to Alexandria residents who happen to overdose somewhere else and people the department identifies as at risk for opioid abuse.) She offers overdose victims and their families her full services to help get them into treatment: She’s made connections with recovery facilities across the state, and she partnered with a local insurance representative to make it easier and faster for people to sign up for coverage. The “Angels” are 12 volunteers Pompilio has recruited to help her handle cases.

“Myself and the Angel will sit down and talk to them about their past history, current stressors in life, their support system, and what has or hasn’t worked,” she explained. She handles the bulk of the logistical legwork of getting people into treatment while the Angels oversee much of the day-to-day duties once they’re out: driving to appointments, helping them find transitional housing, and just being available to meet up or talk over the phone.

Right now, there are nine people in Alexandria’s program, in various stages of recovery: detox, inpatient, outpatient, sober living, or entirely on their own. All of them are in regular communication with their Angel partners. Ward’s officers have stopped charging most people with possession of heroin and other opioids, and they say the Angel program is open to anyone who’s using or might be at risk, not just people who overdose.

Still, there are 36 overdose victims Pompilio hasn’t been able to get into the program this year, plus an unknown number of people who may be using opioids and just haven’t happened to overdose yet. Some aren’t ready or willing to get help, others she simply can’t track down. In these cases, she offers friends and family naloxone kits and leaves her card on the front door. It reads, “We want you to have hope, we want you to experience recovery, we want you to live.”

Nationally, only 1 in 10 people with a substance use disorder gets the treatment they need, according to the surgeon general’s report from last year. The problem in rural areas is further compounded by a lack of access to treatment.

Even a medium-sized city like Cincinnati has one publicly funded detox center, a handful of methadone clinics, and dozens of long-term residential rehab facilities (in addition to many more private facilities). Washington C.H. has just one residential addiction treatment center (for women only), and Alexandria has no opioid addiction treatment facilities of any kind.

It’s been less than a year since the new policies went into effect in both towns, far too soon to say whether one approach is “working” better than the other. In Alexandria, the number of overdoses is on pace to exceed last year’s total, and in Washington C.H., overdoses have already almost doubled. But they are managing to get some people into recovery, including two men who used heroin for years before anyone intervened.

“A person that is using or overdosing already has enough on their plate; this charge doesn’t help.” Chris Conrad, three months sober

Chris Conrad was the 24th drug user charged with inducing panic in Washington C.H. this year. It took four doses of naloxone to revive him when he overdosed in May. On the fourth injection he finally inhaled, but as soon as he took a breath, he vomited. He spent the next 10 days in a hospital in Columbus being treated for aspiration pneumonia to clear the vomit from his lungs. It nearly killed him.

It was his first and only overdose — after almost a decade of using heroin, he’d switched to carfentanil because it was cheaper and easier to get. And even though he was inside a friend’s garage, officers brought the inducing panic charges. A few weeks later, Conrad pleaded guilty and paid a $150 fine plus court costs. A judge ordered him to complete a 90-day treatment program or serve a 90-day jail sentence.

He got a bed at the James K. Marsh House, 75 miles away in Portsmouth. Conrad said the converted single-family home with a porch reminded him of his grandma’s house. The facility’s 16 full-time residents spend about 10 hours a day in classes meant to help them talk openly about their battle with addiction, both in groups and private sessions. Approved visitors can come on Sunday afternoons, when they’ll often barbecue and play cornhole in the backyard.

Conrad, 43, is soft-spoken, with clear blue eyes and tattoos that run up both arms and along the sides of his jawbone. He said he’d been on the facility’s waiting list and had been planning to get clean before he overdosed. He was glad to finally get into treatment, but he’s unhappy with the legal trouble he now faces.

“Court House likes kicking you when you’re down,” he said. “A person that is using or overdosing already has enough on their plate; this charge doesn’t help.”

To make matters worse, Conrad had a prior felony heroin-possession charge unrelated to his overdose, and the court date was set for the middle of his stint in rehab. He couldn’t convince Marsh House administrators to let him leave, and they got into an argument. He walked out a month into his 90-day mandate.

He’s back home working his old job pouring concrete and fixing cars. He said he has no plans to use heroin again and isn’t talking to his old friends, many of whom still use. He plans to enroll in the local outpatient program, Fayette Recovery Center. His probation officer wasn’t aware he’d left Marsh House and wasn’t allowed to speak publicly about his case, but the probation office said Conrad will have to appear in front of the judge again for skipping out on treatment. The judge will decide whether Conrad can enroll in a new program or will have to serve out his 90-day sentence in jail instead.

“Either way, I’m going to do my time or not do my time,” Conrad said. He didn’t seem too concerned, but when asked if he felt recovered, he was less certain. “I’m fine,” he said. “I still think about it, of course, but it’s probably going to be in my head for a long time.”

“The angel program shows addicts that they’re not losers, they’re people.” Chris Northcutt, two years sober

Chris Northcutt had been in and out of prison for two decades when he met Rick Rosenhagen, one of Alexandria’s Angel volunteers. He’d most recently been serving a yearlong sentence for felony heroin possession, and when he was released in March, Alexandria police officers asked if he’d be willing to join the new program.

Rosenhagen paid for Northcutt’s motel that first weekend while they looked for a more permanent sober-living situation. Rosenhagen made phone calls to different residential facilities, and when they found one, he paid for the first month’s rent. Eventually he helped Northcutt find a temporary job rehabbing houses before he landed a full-time gig as a welder at Wolf Steel.

At first Northcutt didn’t understand why Rosenhagen wanted to help, but they slowly got to know each other. “I would tell him, ‘I’m a fucking addict. Why are you helping me?’” said Northcutt, 41, sturdy from his new routine of daily 5 a.m. workouts. “And he would say to me, ‘Why are you putting yourself down? Why are you being so hard on yourself?’”

Rosenhagen was one of the 50 people who showed up to the Angel program’s first meeting last October. A few years earlier, he had mentored a kid who later became addicted to heroin, and over time saw more and more people he knew affected by the drug. He started a Facebook group and eventually a nonprofit, Heroin Support, that raises money for grieving friends and family who have lost someone to an overdose.

“I don’t think a lot of people realize it’s bad here — they think it’s Newport, Covington, Cincinnati — that it’s just an inner-city thing,” Rosenhagen said. “But it’s out here in Alexandria, too.” Northcutt was the first person he worked with as an Angel, and the two became close. “I got to know him, he told me about his past and his relationship with his mother. And I just hope it helped.”

Northcutt was a longtime heroin user. He said he started after being prescribed painkillers to treat a hip injury from a car accident, but the drugs also helped mask years of emotional trauma. When he was using heroin, he estimates that half his hometown of Walton, Kentucky, was using too.

After getting clean during his last prison stay, Northcutt is almost two years heroin-free now. He left his sober living home to move in with his girlfriend in Walton, about 20 miles southwest of Alexandria. He said he hopes to start his own program one day to help those charged with drug offenses find work, but for now he’s still focusing on himself. “Everything I do now is positive; I chase my sobriety just as much as I did getting high.”

In Ohio and Kentucky, as well as nationally, the death toll from opioids continues to rise. In July, a federal commission led by New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie asked the president to declare the opioid crisis a national state of emergency. Doing so would allow states and municipalities to get a boost in funding through the $1.4 billion Disaster Relief Fund, but more importantly, Trump could make changes to Medicaid that would allow more people to access inpatient addiction treatment.

As the federal government tries to determine what to do, states are wrestling with their own response. In Kentucky, Gov. Matt Bevin drafted a proposal to replace the state’s expanded Medicaid program, which increased coverage for treatment services sevenfold, with his own plan, potentially putting coverage for opioid treatment at risk. Still, Bevin approved $15.7 million in state funding to combat the crisis this year, up from $10 million the year before, and directed $1 million to the Department of Corrections to continue treatment programs inside Kentucky’s jails.

In Ohio, Gov. John Kasich continued the state’s $1 billion in funding for drug treatment and prevention, largely considered one of the nation’s most comprehensive responses. And in new guidelines released this year, he urged local communities to start better using state resources to set up local “action teams,” support recovery housing, and equip residents with naloxone, among other recommendations.

That kind of advice can ring a little hollow for the small-town folks on the front lines. They already have local action teams; what they need, they say, is more resources and support.

In the meantime, they’ll keep trying to figure out what else they can do on their own. “We’re all kind of chasing our tails and looking for that answer,” Ward, the Alexandria police chief, said. “But we haven’t found it yet.”

Allison McCann is a data reporter for VICE News Tonight.

Maddie McGarvey is a photographer based in Columbus, Ohio.

Need help with opioid addiction? Find a treatment center near you or find a doctor in your area who offers medication-assisted treatment.