More than a quarter of Ontario’s prison population has been flagged for a possible mental health issue, according to new numbers provided to VICE News in the days after an inmate diagnosed with schizophrenia hanged himself.Justin St. Amour was in the health care unit of the Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre when he attempted suicide by using a bedsheet to hang himself, sources told the Ottawa Citizen. Now he’s on life support, and his mother is preparing herself for the worst.Laureen St. Amour wants to know why her son, who correctional officers said repeatedly threatened or attempted suicide, wasn’t in a psychiatric hospital instead, she told the Citizen.And even as St. Amour lay in the intensive care unit, no one thought to notify his lawyer.“We have nowhere to put them. We put them in segregation a lot of times so that they survive. If we don’t put them in there, a lot of times, they don’t eat. They end up sleeping on the floor. They don’t take their meds.”According to a 2015 report from the John Howard Society of Ontario, which called on the province to “stop relying on the justice system as a key responder to individuals who have mental health issues,” prisoners with the most severe symptoms of mental illness are frequently segregated.The province came under fire last month when the story of a 23-year-old Adam Capay, who had been in solitary confinement, or segregation, for nearly four years while waiting for trial at the Thunder Bay Jail, came to light.Lundy, who has been in regular contact with Capay throughout his time in solitary, said he should’ve had regular access to a psychiatrist, but rarely did.A psychiatrist comes to the jail for just two and a half hours, five times a month.Many correctional officers say they’ve had no choice but to place inmates with mental health alerts in solitary for their own safety or in order to protect themselves and other inmates. Data obtained by the Ontario Human Rights Commissioner reveal that, of the 4,178 prisoners placed in segregation from October to December 2015, 38 percent had a mental health alert on their file. Across Ontario, 21 people have been in segregation cells across Ontario for over a year, VICE News previously reported.That isolation can aggravate their existing symptoms, and cause new effects like hallucination, cognitive disabilities, insomnia, self-mutilation, paranoia, and suicidal tendencies.And the training correctional officers receive to work with mentally ill inmates is “inadequate,” said Lundy.“What [the training] does is it helps people identify different types of mental illness… but what we need is how do we deal with it, so we don’t have to escalate to using force or anything like that,” he said.Correctional officers across Ontario have echoed this concern.Chris Jackel, a correctional officer at the Central North Correctional Centre, which has a capacity of 1,184, said there’s one full-time psychiatrist and three mental health nurses at the prison.The ministry has partnered up with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health to develop enhanced training for correctional officers, which should be completed by this fall.“The people who are acutely unwell are reasonably well-protected in most places,” said Sandy Simpson, chief of forensic psychiatry at CAMH. “There’s another group of people who might be depressed who aren’t telling anybody, who are hearing voices and suffering mental health problems, and finding it hard to talk to anybody.”“Those are probably the people who are getting missed, so they might not have quite so severe, but very important mental health needs, and you have to be very active in your assessment and screening and triage process to find those people,” he said.More than 100 mental health professionals — including psychiatrists, social workers, mental health nurses, and psychologists — provide support services to inmates at 23 provincial facilities, according to the corrections ministry.“At the end of the day, prisons are not hospitals – they are designed for punishment and accountability, not therapeutic intervention,” said Graham Brown of the John Howard Society of Ontario. “Because [the ministry] is responsible for health care in Ontario’s correctional institutions, prisons have these competing mandates: punishment and accountability on the one hand and health care services on the other.”

Data obtained by the Ontario Human Rights Commissioner reveal that, of the 4,178 prisoners placed in segregation from October to December 2015, 38 percent had a mental health alert on their file. Across Ontario, 21 people have been in segregation cells across Ontario for over a year, VICE News previously reported.That isolation can aggravate their existing symptoms, and cause new effects like hallucination, cognitive disabilities, insomnia, self-mutilation, paranoia, and suicidal tendencies.And the training correctional officers receive to work with mentally ill inmates is “inadequate,” said Lundy.“What [the training] does is it helps people identify different types of mental illness… but what we need is how do we deal with it, so we don’t have to escalate to using force or anything like that,” he said.Correctional officers across Ontario have echoed this concern.Chris Jackel, a correctional officer at the Central North Correctional Centre, which has a capacity of 1,184, said there’s one full-time psychiatrist and three mental health nurses at the prison.The ministry has partnered up with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health to develop enhanced training for correctional officers, which should be completed by this fall.“The people who are acutely unwell are reasonably well-protected in most places,” said Sandy Simpson, chief of forensic psychiatry at CAMH. “There’s another group of people who might be depressed who aren’t telling anybody, who are hearing voices and suffering mental health problems, and finding it hard to talk to anybody.”“Those are probably the people who are getting missed, so they might not have quite so severe, but very important mental health needs, and you have to be very active in your assessment and screening and triage process to find those people,” he said.More than 100 mental health professionals — including psychiatrists, social workers, mental health nurses, and psychologists — provide support services to inmates at 23 provincial facilities, according to the corrections ministry.“At the end of the day, prisons are not hospitals – they are designed for punishment and accountability, not therapeutic intervention,” said Graham Brown of the John Howard Society of Ontario. “Because [the ministry] is responsible for health care in Ontario’s correctional institutions, prisons have these competing mandates: punishment and accountability on the one hand and health care services on the other.”

Advertisement

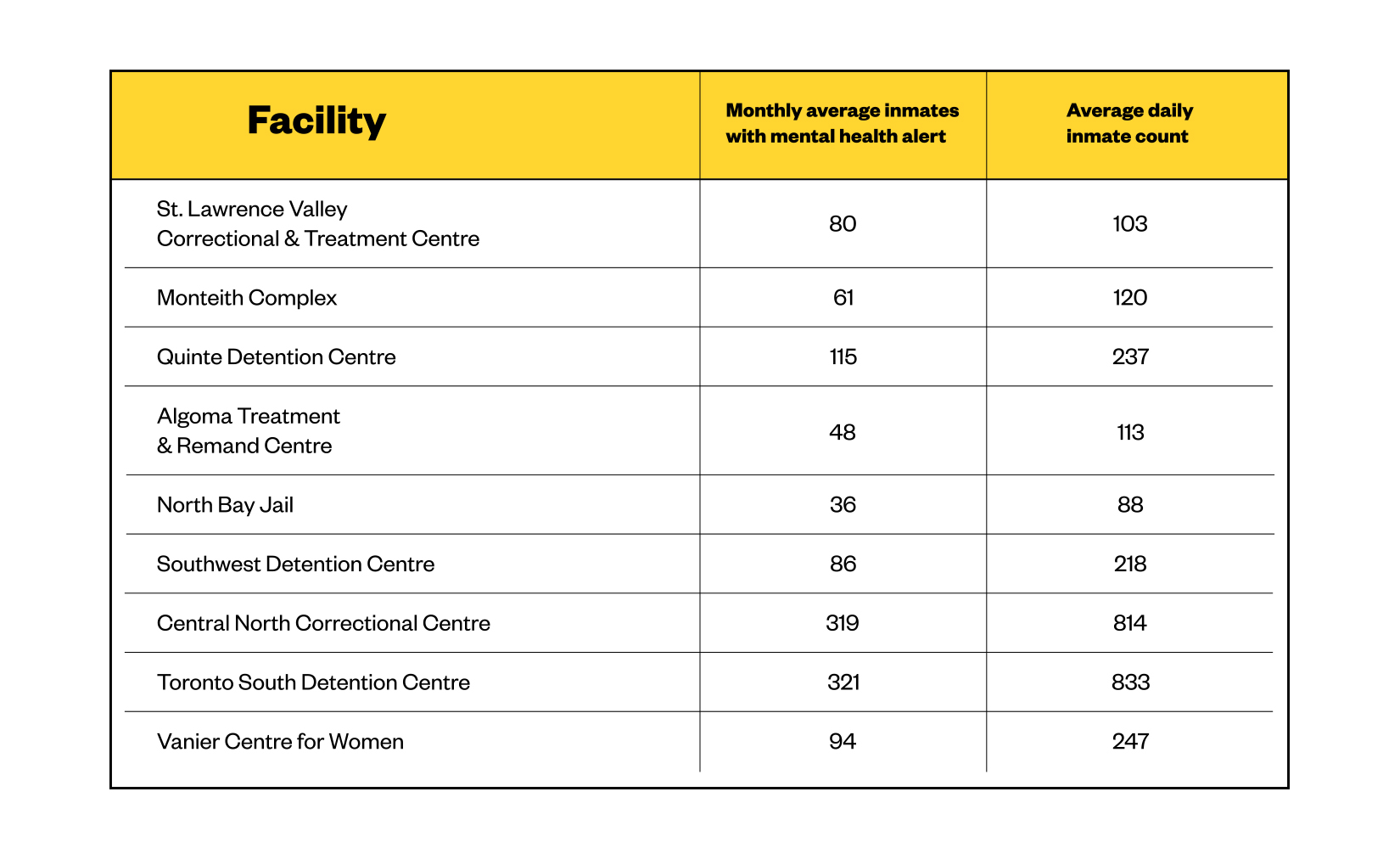

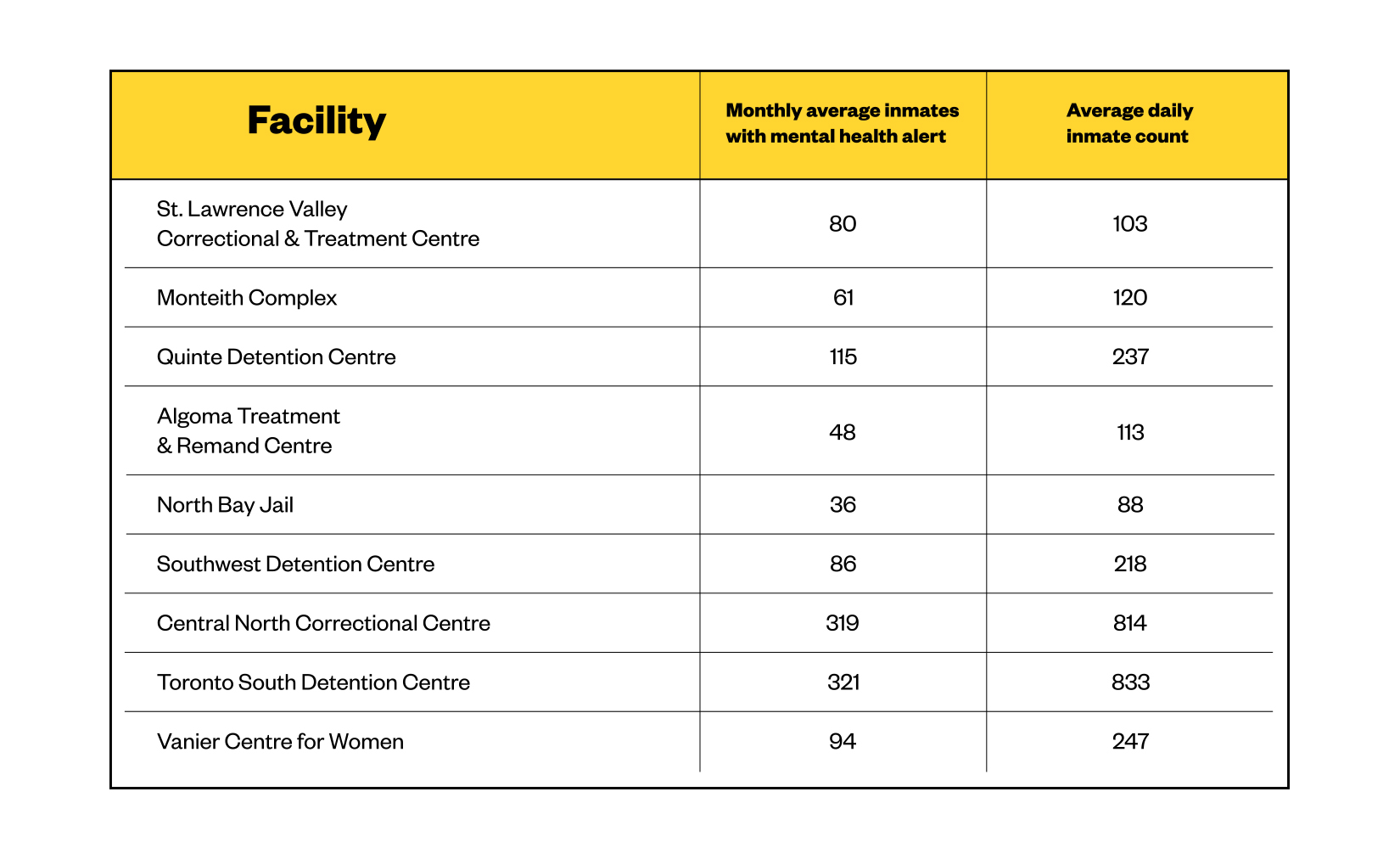

“I was shocked to hear that this had happened,” lawyer Karin Stein told VICE News. “I was very sad and disappointed that nobody had informed me about it. A reporter called me. I hadn’t even read it in the paper yet.”St. Amour is one of many put in a similar situation in Ontario’s over-crowded, under-resourced jails that are struggling to deal with mental health issues within their facilities.VICE News has previously reported how Ontario’s jails are full of inmates who have yet to stand trial, and how the overcrowding issue is leading to a litany of issues.Over the past year, 16,387 provincial inmates had a ‘mental health alert’ attached to their files, or 28 percent of a total of 58,313 prisoners. Those alerts include not only inmates reporting issues themselves, but also “possible management concerns” identified by correctional staff.But the problem may actually be much worse, correctional officers fear, since conditions such as depression or suicidal thoughts are not always visible and can be missed by the untrained eye.“Every single jail in Ontario is overpopulated with mentally ill inmates,” said Mike Lundy, a correctional officer at the Thunder Bay Jail, that on average each month has 43 inmates with mental health alerts, compared to an average population of 132.“Every single jail in Ontario is overpopulated with mentally ill inmates.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

“Is this enough? No,” he said. “While I can’t speak specifically to the work they do, generally, all they have time to do is issue or prescribe meds.”“They don’t have the resources of time to do any counselling or cognitive work,” he said.Andrew Morrison, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services in Ontario, said corrections officers are trained to detect possible signs of mental illness and on how to refer them to professionals who can provide the appropriate level of care.“Inmates also have access to a variety of services and supports including health care, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, regardless of a diagnosis of a specific mental illness,” he said.“At the end of the day, prisons are not hospitals.”

Advertisement