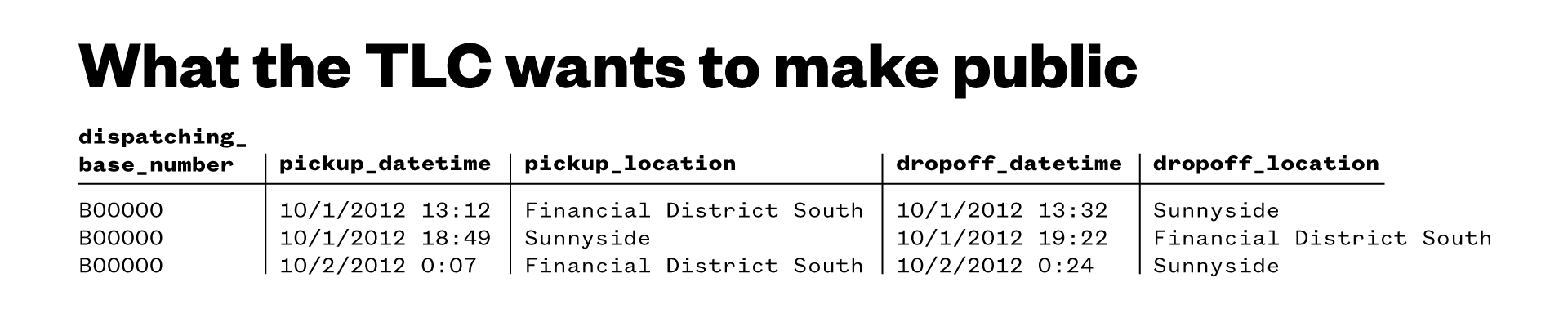

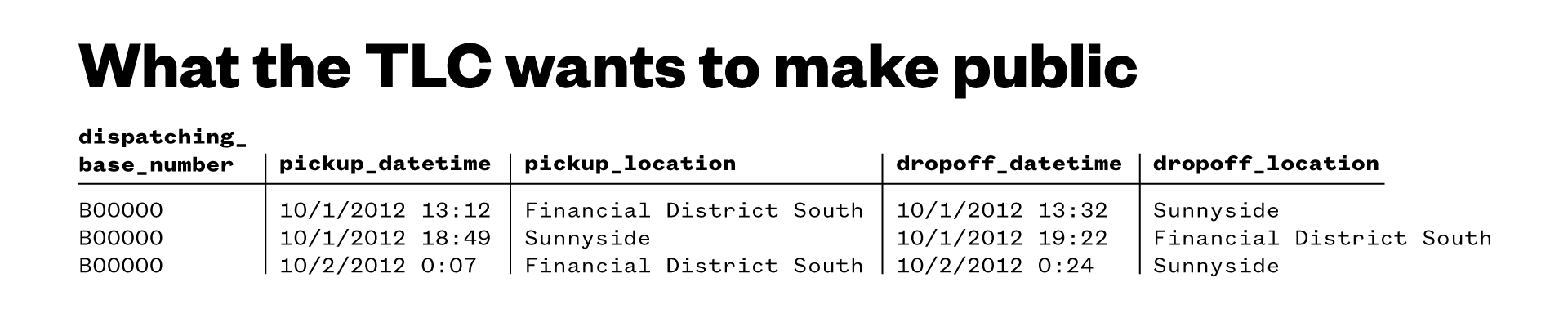

The New York City government wants ride-hailing giant Uber to provide information about where its drivers drop passengers off in order to better measure and combat the problem of “driver fatigue.” But Uber, citing concerns about consumer privacy, doesn’t want to comply.Over the last few years, the NYC government and sharing economy titans have squared off over everything from the allotment of Uber driver taxi licenses to the regulation of so-called “illegal hotels” on Airbnb. In those fights, Uber has largely succeeded in getting what it wants.In the latest chapter of the ongoing drama, Uber this week urged customers over email to “send a clear message” to the city government in response to a proposed rule change from the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission concerning passenger dropoff information. A public hearing on the issue is scheduled for Jan. 5.The city wants this data — not just from Uber, but from all Taxi and Limousine Commission licensees — to help with implementing Mayor Bill DeBlasio’s “Vision Zero” initiative to minimize traffic fatalities.The TLC, which is one of the lead agencies tasked with implementing Vision Zero, wants to take on the problem of driver fatigue. This past summer, the agency ruled that Uber and taxi drivers can drive for only 12 hour shifts with a mandated 8-hour break. The city says it needs passenger dropoff data in order to make sure drivers obey those rules.Uber, in turn, says that it doesn’t want to hand over what it calls “sensitive personal passenger data” on the grounds that it would violate the privacy of its users. The city already collects rough passenger pickup information, and Uber has agreed to provide data about trip duration, but providing specific drop-off information like taxis are obligated to would amount to surveilling individual passengers, Uber argues.“We have an obligation to protect our riders’ data, especially in an age when information collected by government agencies like the TLC can be hacked, shared, misused or otherwise made public,” the company said in a statement.TLC Deputy Commissioner for Public Affairs Allan Fromberg says that consumer data would be more than adequately protected under the TLC proposal. That’s because the information isn’t publicly tied to passenger names or specific drop-off locations, but instead aggregated into “taxi zones.” “Taxi zones are aggregations of census tracts that roughly represent neighborhood areas throughout the city,” Fromberg said. “So instead of the record showing that a passenger was dropped off at a specific address, like 33 Beaver Street in Manhattan, the record instead shows a passenger drop-off in the Financial District South taxi zone.”Uber says that measuring trip duration would be sufficient to determine how much time drivers spend on the road; the San Francisco startup agreed to offer that data to the city. TLC Senior Analyst Madeline Labadie, however, said in an email that both pickup and dropoff information would allow the city to “audit trip data for validity with location information by mapping the trips to ensure we’re receiving accurate data.”Shahid Buttar, civil rights lawyer and director of grassroots advocacy at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said that while he thinks the city’s plan would properly anonymize the data for the public, collecting geographically specific data does pose a security risk.“While TLC’s commitment not to collect passenger identity data is helpful, the proposal would authorize the agency to collect precise location data, which raises vital security concerns that remain unaddressed,” Buttar said. “The destinations of riders comprise a sensitive and lucrative data set that would be vulnerable to theft or malicious hacking.”Gautham Hans, who teaches law at the University of Michigan, believes that Uber was right to characterize this data as “sensitive” to its customers. Hans said that the “mission creep” of government data collection could allow for the data to be used in ways not originally intended, pointing to a 2014 incident in which a New York database inadvertently allowed people to figure out the taxi trip details of celebrities.“I’d want the companies in this instance to comply and continue to work to determine if alternate means could achieve the city’s ends, and work to ensure that data minimization, security, and de-identification standards were put into place,” Hans said. (Though he previously worked with Uber at the Center for Democracy and Technology, Hans says that the company did not financially compensate him.)Uber is clearly conscious of setting precedents. The company, along with Lyft, fought the city of Austin, Texas over mandated fingerprint background checks, which the companies said didn’t work with their business models. Rather than set the precedent of accepting such rules, the ride-hailing services pulled out of Austin.“The privacy concerns that Uber is raising are more concerns about the reputation hit [that Uber] may take,” Hans said. “As with any private firm, they don’t want to be regulated in the way that they are.”

“Taxi zones are aggregations of census tracts that roughly represent neighborhood areas throughout the city,” Fromberg said. “So instead of the record showing that a passenger was dropped off at a specific address, like 33 Beaver Street in Manhattan, the record instead shows a passenger drop-off in the Financial District South taxi zone.”Uber says that measuring trip duration would be sufficient to determine how much time drivers spend on the road; the San Francisco startup agreed to offer that data to the city. TLC Senior Analyst Madeline Labadie, however, said in an email that both pickup and dropoff information would allow the city to “audit trip data for validity with location information by mapping the trips to ensure we’re receiving accurate data.”Shahid Buttar, civil rights lawyer and director of grassroots advocacy at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said that while he thinks the city’s plan would properly anonymize the data for the public, collecting geographically specific data does pose a security risk.“While TLC’s commitment not to collect passenger identity data is helpful, the proposal would authorize the agency to collect precise location data, which raises vital security concerns that remain unaddressed,” Buttar said. “The destinations of riders comprise a sensitive and lucrative data set that would be vulnerable to theft or malicious hacking.”Gautham Hans, who teaches law at the University of Michigan, believes that Uber was right to characterize this data as “sensitive” to its customers. Hans said that the “mission creep” of government data collection could allow for the data to be used in ways not originally intended, pointing to a 2014 incident in which a New York database inadvertently allowed people to figure out the taxi trip details of celebrities.“I’d want the companies in this instance to comply and continue to work to determine if alternate means could achieve the city’s ends, and work to ensure that data minimization, security, and de-identification standards were put into place,” Hans said. (Though he previously worked with Uber at the Center for Democracy and Technology, Hans says that the company did not financially compensate him.)Uber is clearly conscious of setting precedents. The company, along with Lyft, fought the city of Austin, Texas over mandated fingerprint background checks, which the companies said didn’t work with their business models. Rather than set the precedent of accepting such rules, the ride-hailing services pulled out of Austin.“The privacy concerns that Uber is raising are more concerns about the reputation hit [that Uber] may take,” Hans said. “As with any private firm, they don’t want to be regulated in the way that they are.”

Advertisement

Advertisement