GUADALAJARA, Mexico — Mario González hoped the Ayotzinapa teacher training college in southern Guerrero state would provide his 22-year-old son César with a pathway out of poverty. But César was robbed of any future when police officers forcefully disappeared him and 42 male classmates on a hellish September night three years ago in the town of Iguala.Alerted to the incident by one of César’s friends, Gónzalez, a 52-year-old welder from central Tlaxcala state, arrived in Iguala the next morning, but it was too late. The missing students had last been seen packed in patrol cars after a series of ambushes in which police killed six civilians and wounded dozens more.The picture presented by the platform is consistent with independent investigations by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and a group of Argentine forensic experts, all of whom have completely discredited the government’s claims that corrupt local officers handed the students over to cartel assassins who massacred them and burned their bodies after mistaking them for rival gang members.The authorities arrested the Iguala mayor, his wife, and dozens of municipal police officers on charges of kidnapping, murder and organized crime, but the students’ parents suspect that the attacks, which also involved federal agents, were coordinated and covered up by higher-ranking officials.“The Mexican state has lied to us so many times,” González says. “We don’t know how high the blame for the disappearance of our children reaches, but there were very important public officials involved.”González has not worked or returned home since his son’s disappearance. He moved to the Ayotzinapa school with his wife, Hilda, three years ago, and has never left. He dedicates his time to leading demonstrations, meeting investigators, and touring the Americas to raise awareness and put pressure on the Mexican government to solve the case.Despite their efforts to pressure the government, the official investigation has gone cold in the last year.“The attorney general’s office hasn’t wanted to reach the bottom of this case,” González adds. “Unfortunately the law doesn’t exist for us poor people. The law only exists in Mexico to protect the rich.”Left in limbo, with no bodies to bury and no proof that their children are even dead, the parents cling to the faintest hope of finding them alive. “We’ll always have hope until they scientifically prove to us what happened,” González says.The missing students’ parents aren’t the only ones demanding answers. Their classmates who survived that night have also played a prominent role in the search for the truth.Omar García was among a group who managed to escape through Iguala’s dark, narrow streets that night as bullets whizzed past them. The survivors sought treatment for a wounded companion in a local clinic but were told there were no doctors on duty.Moments later a group of soldiers arrived. They photographed the students, took their names and threatened to make them disappear forever.“Me and many others believe this because of the army’s long history of involvement in forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings,” García says. “This should be the primary line of investigation.”

“We’ll always have hope until they scientifically prove to us what happened,” González says.The missing students’ parents aren’t the only ones demanding answers. Their classmates who survived that night have also played a prominent role in the search for the truth.Omar García was among a group who managed to escape through Iguala’s dark, narrow streets that night as bullets whizzed past them. The survivors sought treatment for a wounded companion in a local clinic but were told there were no doctors on duty.Moments later a group of soldiers arrived. They photographed the students, took their names and threatened to make them disappear forever.“Me and many others believe this because of the army’s long history of involvement in forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings,” García says. “This should be the primary line of investigation.” “The army was very much involved,” García insists. “The digital platform shows this wasn’t a coincidence.”Forensic Architecture’s platform very clearly lays out the role of an army intelligence officer who observed and photographed the assault on at least one busload of students.Now living in Mexico City, García is studying law and writing a book on the attacks from the students’ perspective. He has found it hard to move on with his life while campaigning relentlessly for justice.“It’s tiring and frustrating. It makes you sick,” García says. “A lot of our companions have fallen ill and some are even in hospital. It wears you down physically and emotionally, but we’re still here despite all that.”With little alternative but to keep going, the parents and surviving students have planned major demonstrations to mark the third anniversary of a night that will haunt them forever.“The Mexican state wants people to forget, but they’re mistaken,” González adds. “The 43 families will keep fighting and keep mobilizing, despite all that we’ve suffered. They’re not going to silence us.”____________Duncan Tucker is a freelance journalist based in Mexico.

“The army was very much involved,” García insists. “The digital platform shows this wasn’t a coincidence.”Forensic Architecture’s platform very clearly lays out the role of an army intelligence officer who observed and photographed the assault on at least one busload of students.Now living in Mexico City, García is studying law and writing a book on the attacks from the students’ perspective. He has found it hard to move on with his life while campaigning relentlessly for justice.“It’s tiring and frustrating. It makes you sick,” García says. “A lot of our companions have fallen ill and some are even in hospital. It wears you down physically and emotionally, but we’re still here despite all that.”With little alternative but to keep going, the parents and surviving students have planned major demonstrations to mark the third anniversary of a night that will haunt them forever.“The Mexican state wants people to forget, but they’re mistaken,” González adds. “The 43 families will keep fighting and keep mobilizing, despite all that we’ve suffered. They’re not going to silence us.”____________Duncan Tucker is a freelance journalist based in Mexico.

Advertisement

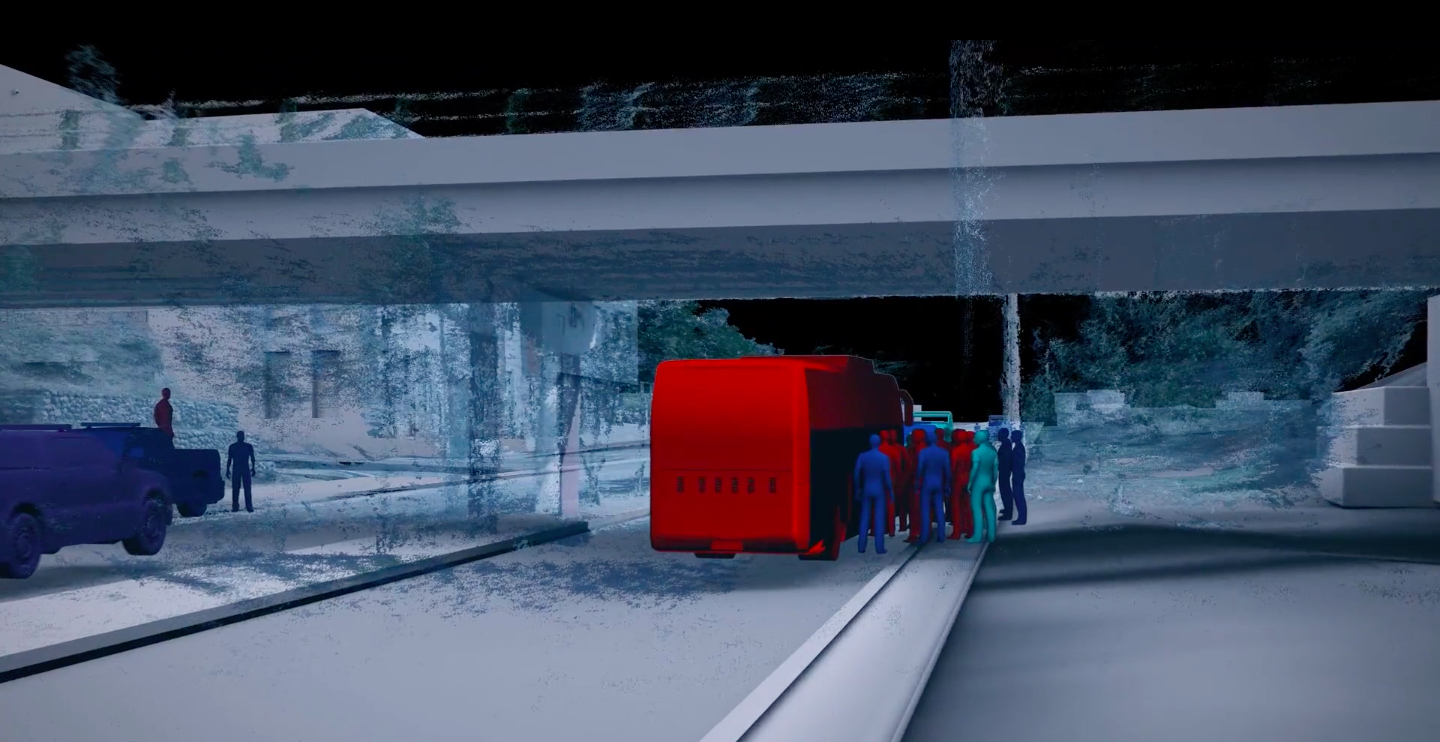

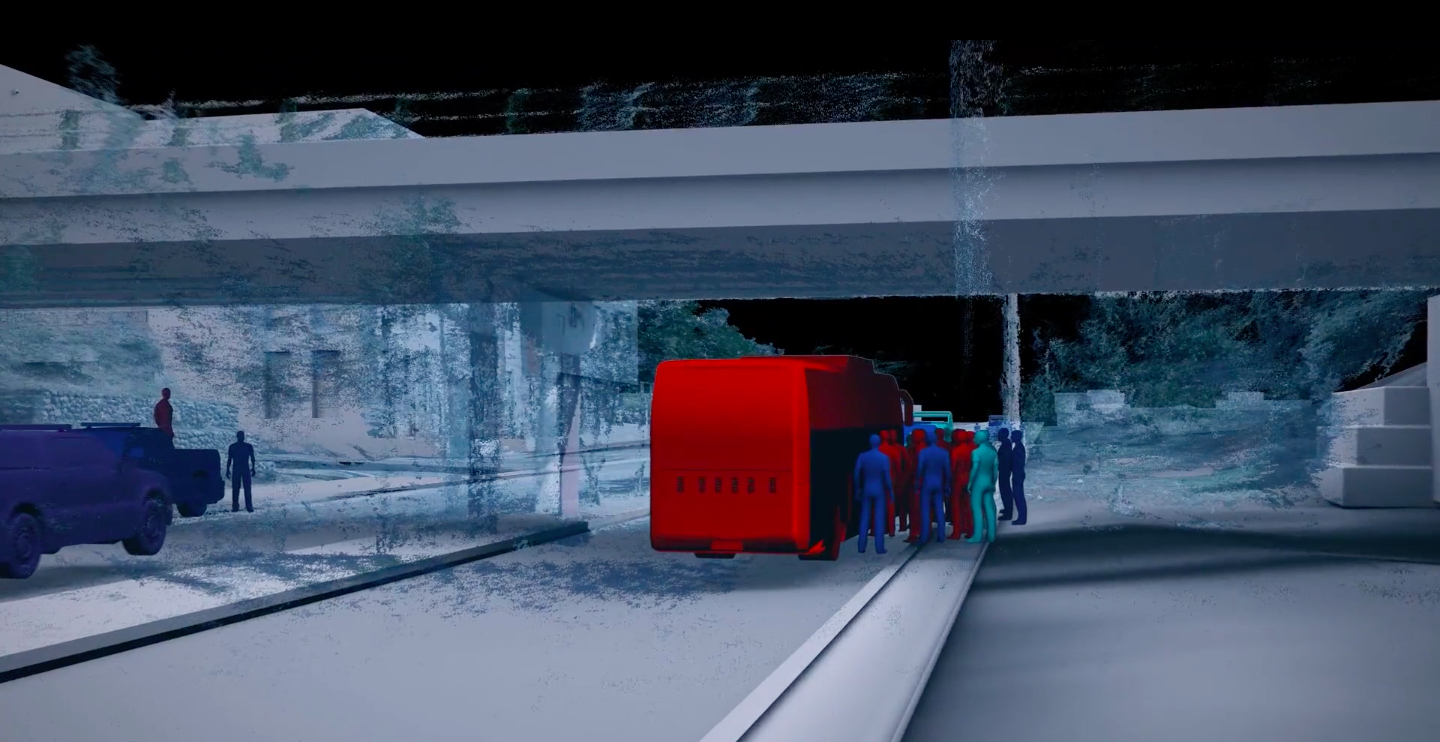

Three years after the attacks, González is still trying to find his son and bring the culprits to justice. But the Mexican government’s widely discredited investigation has stalled, leaving unanswered questions over the level of state involvement in the crime, and robbing parents and survivors of any sense of closure.Forced disappearances are not uncommon in Mexico, where over 32,000 people are currently missing, but Ayotzinapa captured the public’s attention more than any other due to the brutal, calculated manner in which the students were vanished, and the government’s inability to find them.“All 43 families still feel the same pain as if our children had been taken from us yesterday,” González says. “We’re still determined to search for them, find them, and embrace them.”The case and its endless array of inexplicable holes, false confessions, and inconsistencies has pushed parents like González into a world of sleuthing and conspiracy theorizing. Their search received some help this month from British research group Forensic Architecture, which published a digital platform that maps 5,000 data points and allows users to explore an interactive timeline of the attacks on the students. Based on independent investigations, the platform illustrates the highly coordinated nature of the attacks, involving local and federal police officers.“All 43 families still feel the same pain as if our children had been taken from us yesterday.”

Advertisement

The parents have urged the authorities to trace the students’ cellphones, which government investigators say were still in use long after they disappeared. They also seek answers about the role of the army, the involvement of police from nearby Huitzuco, and the growing theory that the students were attacked because they unknowingly commandeered a bus stashed with a drug shipment.“We’ll always have hope until they scientifically prove to us what happened.”

Advertisement

The troops were stationed just a mile away, but they did nothing to stop the police firing on unarmed civilians. The government has refused to investigate their role in the disappearances.Months later, García and a group of students were beaten back when they tried to force their way into the army base where they suspect their classmates were held.“It’s tiring and frustrating. It makes you sick.”

Advertisement