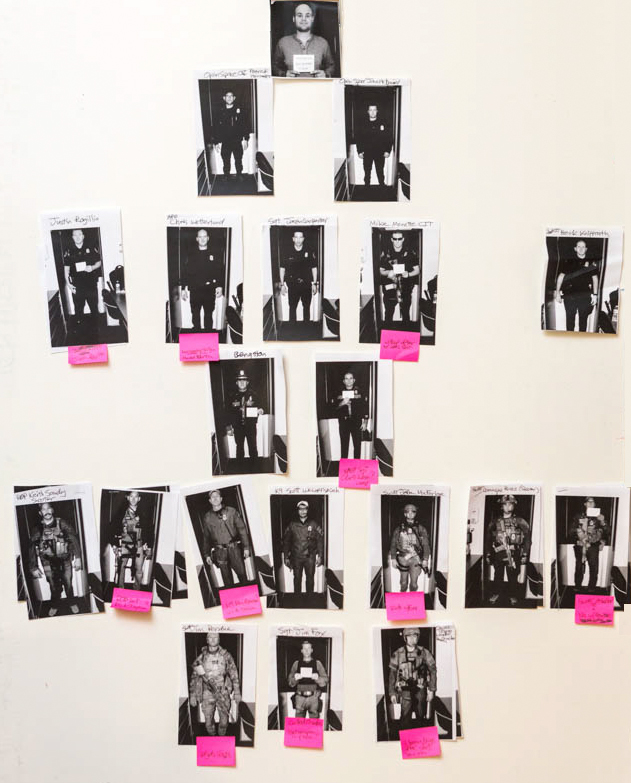

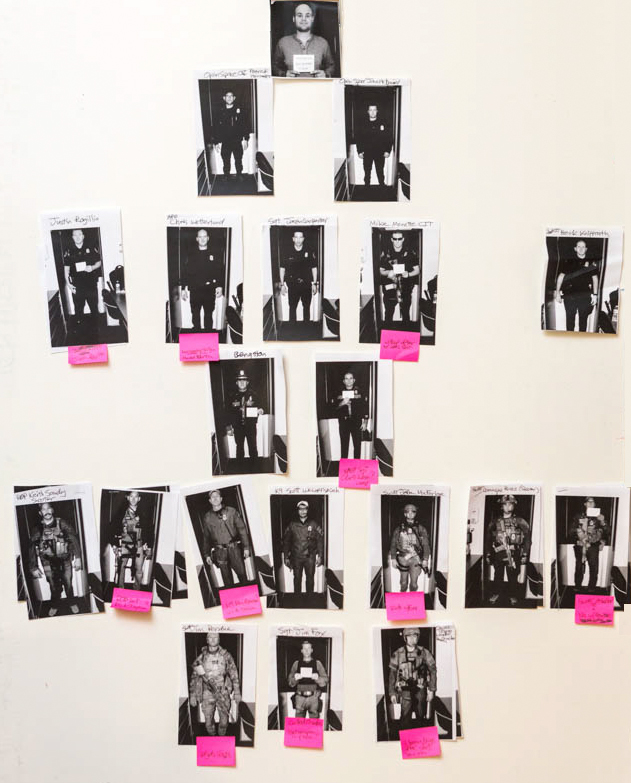

It was April 2015 when Randi McGinn got the call. The district attorney sounded discouraged. Three months earlier, the DA had charged two of the city’s police officers, Keith Sandy and Dominique Perez, with murder for the March 2014 shooting of a homeless man named James Boyd, following a three-hour standoff in the foothills of eastern Albuquerque. At the time he was shot, Boyd was surrounded by a total of 19 officers, including several pointing rifles, two with K-9 dogs, two tactical squads, and a sniper. Boyd was holding two knives. An officer’s helmet camera recorded the encounter, and after the police department released it to the public, hundreds of people marched in the streets for hours. It was one of the first videos of a police shooting to go public, still five months before Ferguson would galvanize nationwide calls to hold police accountable for killing civilians.Kari Brandenburg, the Bernalillo County DA, thought she had a case. But she faced a dilemma. Albuquerque police had launched their own criminal investigation accusing her of bribing and intimidating a witness involved in a past arrest of her son. Some believed the cops were retaliating against her. But the damage had been done. A judge ordered that Brandenburg remove herself from the Boyd case. She needed to find a replacement quickly, or the case would likely be dismissed, and the officers would walk free.Brandenburg contacted the other district attorneys in New Mexico plus the state’s attorney general — 13 in all. No one wanted the case. “It was a political bomb,” she told me.Brandenburg continued down her list. She called McGinn, a longtime trial attorney known for winning some of the biggest civil settlements the state had seen, including millions in payouts from insurance giants and police departments. “Randi was aware of the controversies, of the position it could possibly put her in — that she may become the target of what I became the target of,” Brandenburg said. “She always makes doing what she feels is right a top priority, and I thought I could appeal to those qualities.” McGinn had, of course, been following the Boyd case. Now she listened at the other end of the line, incredulous. It wasn’t that the other DAs had reviewed the case and determined it wasn’t worth prosecuting. “No one even wanted to look at the file,” she said. McGinn agreed to take the case and to charge a flat fee, $5,400 — the same amount that courts typically paid to contract public defenders in an ordinary murder case.No Albuquerque police officer had been charged for a fatal shooting in at least 50 years. Until Boyd’s death, Brandenburg had never sought criminal charges against any of the officers involved in the deadly shootings that took place during her 14-year tenure. But lately, they appeared to be happening at an alarming clip. Between 2010 and 2014, deadly shootings by the city’s police officers had claimed the lives of 28 people, a per capita rate twice that of Chicago and more than eight times that of New York City.One month after the Boyd shooting, a Department of Justice report found that a majority of shootings by Albuquerque police between 2009 and 2012 were unreasonable, using “deadly force in circumstances where there is no imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm to officers or others.” The DOJ also found that Albuquerque cops used fatal force in situations where “the officers heightened the danger and contributed to the need to use force.”“We are in a crisis that I’m not sure we can recover from,” Brandenburg said at a press conference announcing McGinn’s appointment to the Boyd case, citing a lack of faith in law enforcement and government. “There is a feeling of impotence,” she added, “because nobody seems to be getting anything done.”To McGinn, it was this sense of intractability that was prompting the protests in Albuquerque and across the country. A 2015 analysis of fatal police shootings by the Washington Post found that out of thousands of shootings since 2005, only 54 officers had been charged, and just 11 of those convicted. Many of those shootings were being justified behind closed doors, whether by the DA, the police chief, or a secret grand jury.McGinn would not get a conviction; the jurors would deadlock on the verdict for both officers. But over the next 18 months, McGinn would try to lay out a blueprint for holding cops publicly accountable for fatal shootings — and she would experience, firsthand, why they were virtually impossible to prosecute.

McGinn had, of course, been following the Boyd case. Now she listened at the other end of the line, incredulous. It wasn’t that the other DAs had reviewed the case and determined it wasn’t worth prosecuting. “No one even wanted to look at the file,” she said. McGinn agreed to take the case and to charge a flat fee, $5,400 — the same amount that courts typically paid to contract public defenders in an ordinary murder case.No Albuquerque police officer had been charged for a fatal shooting in at least 50 years. Until Boyd’s death, Brandenburg had never sought criminal charges against any of the officers involved in the deadly shootings that took place during her 14-year tenure. But lately, they appeared to be happening at an alarming clip. Between 2010 and 2014, deadly shootings by the city’s police officers had claimed the lives of 28 people, a per capita rate twice that of Chicago and more than eight times that of New York City.One month after the Boyd shooting, a Department of Justice report found that a majority of shootings by Albuquerque police between 2009 and 2012 were unreasonable, using “deadly force in circumstances where there is no imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm to officers or others.” The DOJ also found that Albuquerque cops used fatal force in situations where “the officers heightened the danger and contributed to the need to use force.”“We are in a crisis that I’m not sure we can recover from,” Brandenburg said at a press conference announcing McGinn’s appointment to the Boyd case, citing a lack of faith in law enforcement and government. “There is a feeling of impotence,” she added, “because nobody seems to be getting anything done.”To McGinn, it was this sense of intractability that was prompting the protests in Albuquerque and across the country. A 2015 analysis of fatal police shootings by the Washington Post found that out of thousands of shootings since 2005, only 54 officers had been charged, and just 11 of those convicted. Many of those shootings were being justified behind closed doors, whether by the DA, the police chief, or a secret grand jury.McGinn would not get a conviction; the jurors would deadlock on the verdict for both officers. But over the next 18 months, McGinn would try to lay out a blueprint for holding cops publicly accountable for fatal shootings — and she would experience, firsthand, why they were virtually impossible to prosecute. The thing that always struck McGinn about the Boyd case were the odds. On March 16, 2014, around 3:54 p.m., a resident of a house abutting Albuquerque’s eastern foothills called the police to report that two people had been living in the rocks. The area was part of a designated city park, where camping was illegal. When two officers arrived, about an hour later, Boyd was sitting under a tarp. They asked Boyd to step out and show his hands.Boyd stepped out. “Why do you raise your weapons at me?” he asked. Boyd told them he had a matter of national security to discuss and had been trying to contact the cops for five months. “I am actually your supervisor in an incident against the Department of Defense.” One officer patted Boyd down after spotting a knife hanging from his belt. “Please don’t touch me,” Boyd said, pulling out two knives from his pockets. The officers ordered Boyd to drop the knives. They called for backup.Over the next three hours, seven field officers, seven tactical team officers, then three SWAT team members arrived at the scene, in three waves. A radio dispatcher notified the officers: “James has an extensive criminal history of aggravated battery on peace officers in various jurisdictions, including Albuquerque. It has been reported that he is a paranoid schizophrenic. He is a transient that is known to frequent public libraries. Use extreme caution when contacting James.”By 7:06 p.m., three officers, including Keith Sandy, stood on the hillside closest to Boyd. They devised a plan to subdue Boyd using a Taser shotgun or by unleashing a K-9 dog on him.Boyd alternated between verbally threatening the officers and making friendly conversation. “I’m going to hunt you down and kill you,” he said, then later offered the officers coffee and water. He explained that he thought his camp was legal, and was confused about why the officers were there. At one point during the standoff, he said, “I want to go back to my family and start over somewhere, get back together. I haven’t seen my family for 20 years, man, because I’ve been working to save lives and this is what I get: I get murdered.”

The thing that always struck McGinn about the Boyd case were the odds. On March 16, 2014, around 3:54 p.m., a resident of a house abutting Albuquerque’s eastern foothills called the police to report that two people had been living in the rocks. The area was part of a designated city park, where camping was illegal. When two officers arrived, about an hour later, Boyd was sitting under a tarp. They asked Boyd to step out and show his hands.Boyd stepped out. “Why do you raise your weapons at me?” he asked. Boyd told them he had a matter of national security to discuss and had been trying to contact the cops for five months. “I am actually your supervisor in an incident against the Department of Defense.” One officer patted Boyd down after spotting a knife hanging from his belt. “Please don’t touch me,” Boyd said, pulling out two knives from his pockets. The officers ordered Boyd to drop the knives. They called for backup.Over the next three hours, seven field officers, seven tactical team officers, then three SWAT team members arrived at the scene, in three waves. A radio dispatcher notified the officers: “James has an extensive criminal history of aggravated battery on peace officers in various jurisdictions, including Albuquerque. It has been reported that he is a paranoid schizophrenic. He is a transient that is known to frequent public libraries. Use extreme caution when contacting James.”By 7:06 p.m., three officers, including Keith Sandy, stood on the hillside closest to Boyd. They devised a plan to subdue Boyd using a Taser shotgun or by unleashing a K-9 dog on him.Boyd alternated between verbally threatening the officers and making friendly conversation. “I’m going to hunt you down and kill you,” he said, then later offered the officers coffee and water. He explained that he thought his camp was legal, and was confused about why the officers were there. At one point during the standoff, he said, “I want to go back to my family and start over somewhere, get back together. I haven’t seen my family for 20 years, man, because I’ve been working to save lives and this is what I get: I get murdered.” Boyd grew up in a small town in southern New Mexico, according to Shannon Kennedy, who represented his family in their wrongful death lawsuit. Andrew Jones, Boyd’s half-brother, remembered spending hours together gazing through a telescope or taking apart bicycles and rebuilding them. When Boyd was 19, Kennedy said, he was arrested while trying to get onto a military base. He hit an officer while trying to escape jail, and for that a judge sentenced Boyd to 10 years in state prison. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia a few years later. He was sometimes shuttled to the New Mexico Behavioral Health Institute — the only psychiatric hospital in the state — to receive counseling and treatment. Jones and his mother had tried for several years to find his brother, and when Jones finally reached the hospital, he was told Boyd had been released and put on a bus. According to the medical examiner’s report, Boyd was last seen at an Albuquerque hospital in October 2010, after being detained for loitering outside the Kirtland Air Force Base. He had told medical staff that he had not been paid for covert work he did for the military.Little is known about how Boyd wound up in the foothills. There were rumors that he had set up camp there before, perhaps after growing weary of a life between shelters and the street. To Jones, the foothills made perfect sense. Boyd had loved the outdoors. He taught Jones how to camp and read the constellations in the night sky. It wasn’t hard to imagine how Boyd might have found a small patch of hillside at the edge of the city, tucked between boulders and cacti and shrubs. It was quiet there. And on March 16, 2014, it was sunny, warm enough that the shelters he frequented had closed. Boyd might have set up a tarp for shade, catching the occasional breeze, staring out at the city spread below.As night fell on the foothills, Boyd, surrounded by cops, grew increasingly agitated and anxious. “I’m going to get shot and put in the newspaper,” he said.Around 7:29 p.m., Boyd finally told the officers, warily, that he would begin walking with them. “I love folks,” Boyd said. “Don’t try to harm me. Keep your word, I can keep you safe. Alright. Don’t worry about safety. I’m not a fucking murderer. Alright. Fine. Don’t try to harm me — I’m not trying to harm you. Alright?”Then, one officer said, “Bang this fucker now.” A flash bang went off at Boyd’s feet.Three minutes later, two officers opened fire — first Sandy, then Perez, who had run up to the scene a few minutes earlier. Boyd collapsed face-down.Each officer fired three bullets. The first scraped Boyd’s chest and lodged into his upper left arm. Another struck his right arm, shattering his humerus bone. A third bullet grazed his gray sweatshirt. A fourth one entered Boyd’s lower back. An ambulance took Boyd to a hospital trauma ward, where a surgeon opened his chest and amputated his arm to control the bleeding. At 2:55 a.m. the next day, Boyd was declared dead. A toxicology report showed no trace of drugs.“What you cannot see from the videotape is that it wasn’t just two officers versus Mr. Boyd, or four officers versus Mr. Boyd,” McGinn later told the jury. “In fact, at the time of the shooting, there were 19 police officers up there.” McGinn tallied the numbers. The officers had brought a total of 28 firearms to the foothills. The guns that killed Boyd were high-powered rifles, with soft-point bullets, intended to cause maximum damage. Boyd was just “one person who brought knives to a gunfight,” she said.

Boyd grew up in a small town in southern New Mexico, according to Shannon Kennedy, who represented his family in their wrongful death lawsuit. Andrew Jones, Boyd’s half-brother, remembered spending hours together gazing through a telescope or taking apart bicycles and rebuilding them. When Boyd was 19, Kennedy said, he was arrested while trying to get onto a military base. He hit an officer while trying to escape jail, and for that a judge sentenced Boyd to 10 years in state prison. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia a few years later. He was sometimes shuttled to the New Mexico Behavioral Health Institute — the only psychiatric hospital in the state — to receive counseling and treatment. Jones and his mother had tried for several years to find his brother, and when Jones finally reached the hospital, he was told Boyd had been released and put on a bus. According to the medical examiner’s report, Boyd was last seen at an Albuquerque hospital in October 2010, after being detained for loitering outside the Kirtland Air Force Base. He had told medical staff that he had not been paid for covert work he did for the military.Little is known about how Boyd wound up in the foothills. There were rumors that he had set up camp there before, perhaps after growing weary of a life between shelters and the street. To Jones, the foothills made perfect sense. Boyd had loved the outdoors. He taught Jones how to camp and read the constellations in the night sky. It wasn’t hard to imagine how Boyd might have found a small patch of hillside at the edge of the city, tucked between boulders and cacti and shrubs. It was quiet there. And on March 16, 2014, it was sunny, warm enough that the shelters he frequented had closed. Boyd might have set up a tarp for shade, catching the occasional breeze, staring out at the city spread below.As night fell on the foothills, Boyd, surrounded by cops, grew increasingly agitated and anxious. “I’m going to get shot and put in the newspaper,” he said.Around 7:29 p.m., Boyd finally told the officers, warily, that he would begin walking with them. “I love folks,” Boyd said. “Don’t try to harm me. Keep your word, I can keep you safe. Alright. Don’t worry about safety. I’m not a fucking murderer. Alright. Fine. Don’t try to harm me — I’m not trying to harm you. Alright?”Then, one officer said, “Bang this fucker now.” A flash bang went off at Boyd’s feet.Three minutes later, two officers opened fire — first Sandy, then Perez, who had run up to the scene a few minutes earlier. Boyd collapsed face-down.Each officer fired three bullets. The first scraped Boyd’s chest and lodged into his upper left arm. Another struck his right arm, shattering his humerus bone. A third bullet grazed his gray sweatshirt. A fourth one entered Boyd’s lower back. An ambulance took Boyd to a hospital trauma ward, where a surgeon opened his chest and amputated his arm to control the bleeding. At 2:55 a.m. the next day, Boyd was declared dead. A toxicology report showed no trace of drugs.“What you cannot see from the videotape is that it wasn’t just two officers versus Mr. Boyd, or four officers versus Mr. Boyd,” McGinn later told the jury. “In fact, at the time of the shooting, there were 19 police officers up there.” McGinn tallied the numbers. The officers had brought a total of 28 firearms to the foothills. The guns that killed Boyd were high-powered rifles, with soft-point bullets, intended to cause maximum damage. Boyd was just “one person who brought knives to a gunfight,” she said. “He gets shot like this,” McGinn told me on a recent afternoon in her office. She leaned forward in a black leather chair, her silvery blonde hair falling over her cheekbones, and reached both arms straight out. With one hand she traced the bullet trajectory from her lower spine, across and up to the right. “It went through all of his organs, and ended up in his shoulder.”A large painting hung on the wall in front of McGinn, of a Native American woman shielding herself from a flock of flapping roosters —“It’s a woman warrior taking on all the chickens,” she explained. McGinn, who is 61, speaks in an airy, soprano voice. She flashed a smile that exuded both the warmth of a school teacher and the chill of an interrogator. In her earlier years as a trial attorney, a colleague once called her the “120-pound great white shark.” McGinn grew up in Alamagordo, a remote town in southern New Mexico near an Air Force base where her father served. She remembers riding horses and racing barrels at the rodeo. “Back then we couldn’t do the stuff with the ropes like the boys could,” she said. As a young girl, she was often teased for being chubby, and even after a growth spurt transformed her into tall, thin, boy-crush material, she never forgot about the teasing. She started playing tennis. She liked the competition. She especially liked beating the boys.

“He gets shot like this,” McGinn told me on a recent afternoon in her office. She leaned forward in a black leather chair, her silvery blonde hair falling over her cheekbones, and reached both arms straight out. With one hand she traced the bullet trajectory from her lower spine, across and up to the right. “It went through all of his organs, and ended up in his shoulder.”A large painting hung on the wall in front of McGinn, of a Native American woman shielding herself from a flock of flapping roosters —“It’s a woman warrior taking on all the chickens,” she explained. McGinn, who is 61, speaks in an airy, soprano voice. She flashed a smile that exuded both the warmth of a school teacher and the chill of an interrogator. In her earlier years as a trial attorney, a colleague once called her the “120-pound great white shark.” McGinn grew up in Alamagordo, a remote town in southern New Mexico near an Air Force base where her father served. She remembers riding horses and racing barrels at the rodeo. “Back then we couldn’t do the stuff with the ropes like the boys could,” she said. As a young girl, she was often teased for being chubby, and even after a growth spurt transformed her into tall, thin, boy-crush material, she never forgot about the teasing. She started playing tennis. She liked the competition. She especially liked beating the boys. McGinn’s winning streak continued in the courtroom: Out of more than 120 cases that she tried, she had lost only five. Her first big case, while working as a prosecutor in the ’80s, involved a man who had killed a police officer; she put him on death row. In 1984, McGinn left the DA’s office and the next year opened her own firm, starting out with small auto accidents and criminal defense cases.McGinn loves being a trial lawyer for two major reasons. For one, it’s like “storytelling on steroids,” she likes to say, and telling stories is what she was born to do. And it gives her access to power. “If someone is abusing the law, it teaches you where to throw the wrench to gum up the works and keep the judicial steamroller from crushing your client.”

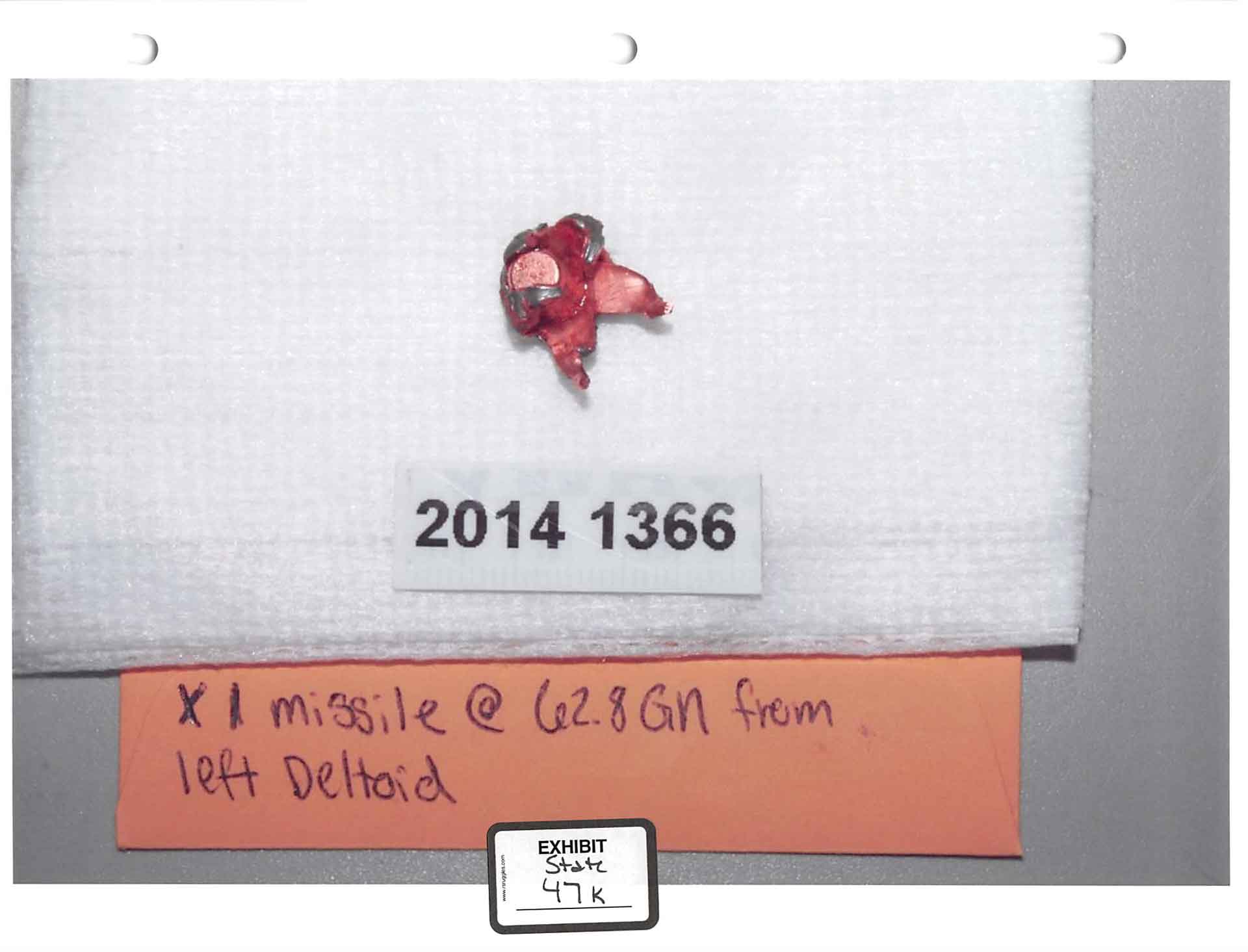

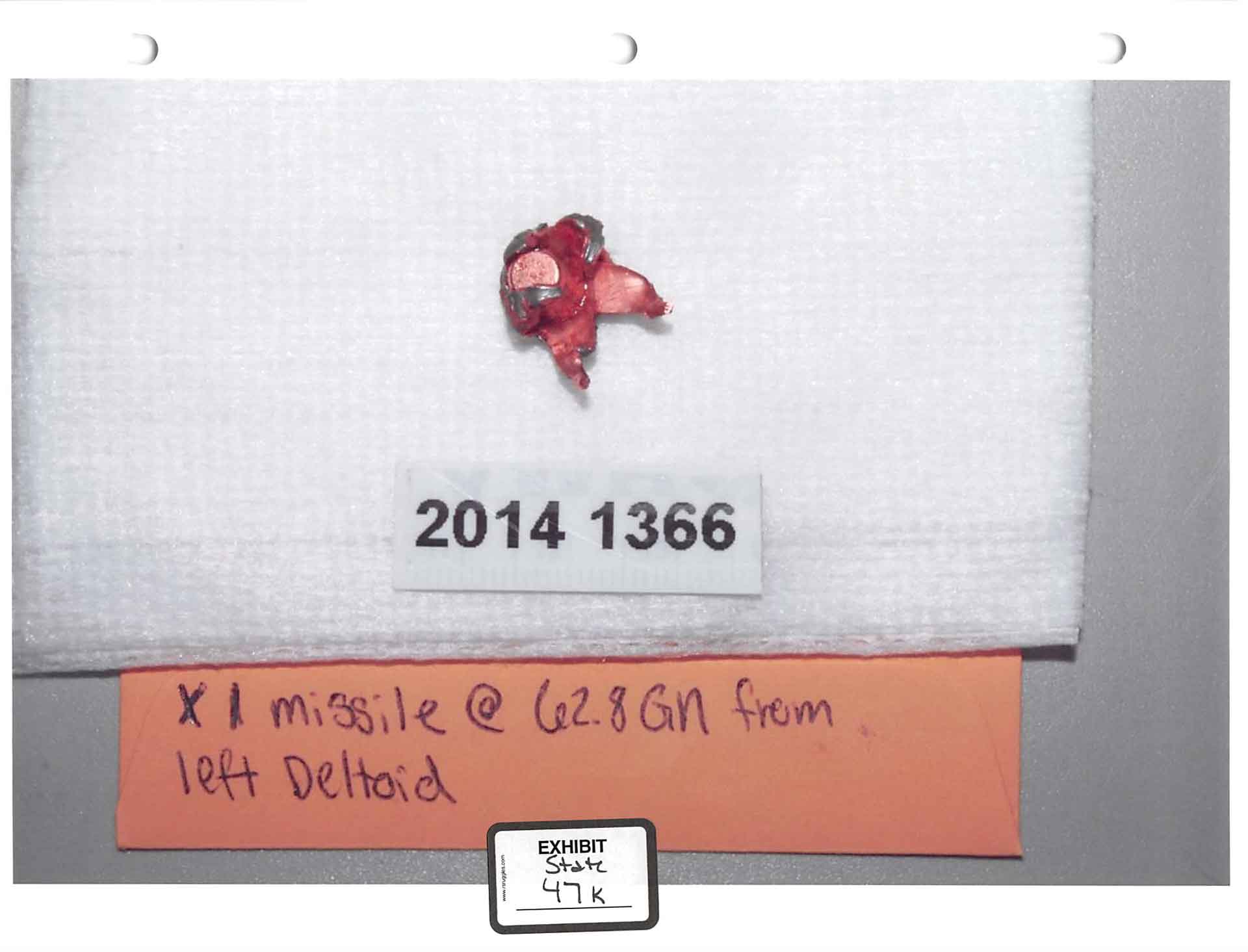

McGinn’s winning streak continued in the courtroom: Out of more than 120 cases that she tried, she had lost only five. Her first big case, while working as a prosecutor in the ’80s, involved a man who had killed a police officer; she put him on death row. In 1984, McGinn left the DA’s office and the next year opened her own firm, starting out with small auto accidents and criminal defense cases.McGinn loves being a trial lawyer for two major reasons. For one, it’s like “storytelling on steroids,” she likes to say, and telling stories is what she was born to do. And it gives her access to power. “If someone is abusing the law, it teaches you where to throw the wrench to gum up the works and keep the judicial steamroller from crushing your client.” By the time McGinn began her investigation, in April 2015, more than a year had passed since Boyd’s death. In an ordinary homicide investigation, the police department would have reconstructed the crime scene, examined the weapons, and locked up the evidence. But as McGinn read the homicide detective’s 885-page report, she noticed that key pieces of evidence were still missing. “When I was a prosecutor, the case would be handed to me and it would all be put together,” McGinn said. “You could almost walk into court with the file. That didn’t happen here.”McGinn started with the medical examiner’s office. In his ballistics report, an Albuquerque police forensic scientist had written that he was unable to match the one bullet retrieved from the scene of the shooting — the one that had entered Boyd’s back — “due to insufficient individual characteristics.” The other bullets had shattered as they pierced Boyd’s limbs and collided with the rocks around him. Without a bullet match, it wasn’t possible to conclude which officers had shot Boyd. But after interviewing the examiner who conducted Boyd’s autopsy and reviewing a photo of the bullet, McGinn saw that the bullet was almost fully intact, with tiny pieces of Boyd’s jacket still stuck to it. “It didn’t make any sense,” she said.McGinn had the bullet sent to Rocky Edwards, a forensic scientist and police officer in Santa Ana, California. A few days later, he called back. Typically, bullets retrieved from murder scenes are cleaned in order to see their grooves and markings — their unique identifiers. But this bullet still had blood on it. “That raises some concerns about whether they really tried to match it or not,” McGinn said. After examining the bullet through his microscope, Edwards determined that the bullet was fired from Dominique Perez’s gun.

By the time McGinn began her investigation, in April 2015, more than a year had passed since Boyd’s death. In an ordinary homicide investigation, the police department would have reconstructed the crime scene, examined the weapons, and locked up the evidence. But as McGinn read the homicide detective’s 885-page report, she noticed that key pieces of evidence were still missing. “When I was a prosecutor, the case would be handed to me and it would all be put together,” McGinn said. “You could almost walk into court with the file. That didn’t happen here.”McGinn started with the medical examiner’s office. In his ballistics report, an Albuquerque police forensic scientist had written that he was unable to match the one bullet retrieved from the scene of the shooting — the one that had entered Boyd’s back — “due to insufficient individual characteristics.” The other bullets had shattered as they pierced Boyd’s limbs and collided with the rocks around him. Without a bullet match, it wasn’t possible to conclude which officers had shot Boyd. But after interviewing the examiner who conducted Boyd’s autopsy and reviewing a photo of the bullet, McGinn saw that the bullet was almost fully intact, with tiny pieces of Boyd’s jacket still stuck to it. “It didn’t make any sense,” she said.McGinn had the bullet sent to Rocky Edwards, a forensic scientist and police officer in Santa Ana, California. A few days later, he called back. Typically, bullets retrieved from murder scenes are cleaned in order to see their grooves and markings — their unique identifiers. But this bullet still had blood on it. “That raises some concerns about whether they really tried to match it or not,” McGinn said. After examining the bullet through his microscope, Edwards determined that the bullet was fired from Dominique Perez’s gun. Then there were the weapons. Sandy and Perez had each fired their rifles. McGinn expected that they would be stored in an evidence locker. But after being tested and photographed, the guns had been returned to the field. Later, when McGinn and her team tried to enter the guns as evidence to show the jury, Sandy and Perez’s attorneys objected, arguing that the guns were no longer in the state they had been in at the time of the shooting. The judge agreed.There was also no record of Albuquerque PD having reconstructed the crime scene. McGinn took her staff to the foothills, where the group met Geoff Stone, the homicide detective who initially investigated the shooting. Stone positioned silhouette cut-outs of several officers where they would have been standing during the shooting. McGinn placed herself in the spot where Boyd had been shot. From there, she began to see the full story.

Then there were the weapons. Sandy and Perez had each fired their rifles. McGinn expected that they would be stored in an evidence locker. But after being tested and photographed, the guns had been returned to the field. Later, when McGinn and her team tried to enter the guns as evidence to show the jury, Sandy and Perez’s attorneys objected, arguing that the guns were no longer in the state they had been in at the time of the shooting. The judge agreed.There was also no record of Albuquerque PD having reconstructed the crime scene. McGinn took her staff to the foothills, where the group met Geoff Stone, the homicide detective who initially investigated the shooting. Stone positioned silhouette cut-outs of several officers where they would have been standing during the shooting. McGinn placed herself in the spot where Boyd had been shot. From there, she began to see the full story.

The way McGinn saw it, there were two pivotal moments where the shooting could have been avoided. The first was the period of time when Boyd spoke with Mikal Monette, a crisis intervention officer who specialized in negotiating with people with mental illness. On the day of the shooting, Monette was the third officer who arrived at Boyd’s camp. Within 22 minutes of speaking to Boyd, Monette testified, he had stopped taking out his knives and making threats.But after Sandy and other tactical officers arrived, Monette was told to move away from Boyd. Monette later testified that in his five years as a police officer, he had successfully talked down hundreds of people with mental illnesses. Boyd was the only time he had failed.The second pivotal moment began when then-SWAT Sergeant James Fox arrived, 13 minutes prior to the shooting. Fox testified that he first set up a command post at the bottom of the foothills and checked in with officers on the scene. He then began to establish an inner perimeter, and was sending up a beanbag shotgun that had been requested by the officers closest to Boyd. He’d planned to bring in crisis negotiators next. Fox hoped his plan would “slow it down as much as I can.” He didn’t know that Boyd had been ordered to walk down the hill. A SWAT officer with the beanbag shotgun made it halfway up to Boyd when the gunshots went off.“At those two moments, this could have been resolved peacefully,” McGinn said. “The common denominator in both of them was Keith Sandy.”On the day of the shooting, Sandy received a call from a radio dispatcher requesting that a beanbag shotgun be brought to the foothills. A few minutes later, the dispatcher called back to say they had meant to call a different tactical unit but called him by mistake. Sandy, who had just returned from church with his family, told the dispatcher he was already on his way.When he arrived at the foothills, Sandy put on a plated vest and slung a rifle and Taser shotgun over his shoulders. He checked the handgun in his holster and two flash bangs in his pocket. He bantered with a state police officer, asking why he was called to the scene. “What do they got you here for?”“I don’t know,” the other officer replied. “The guy asked for state police,” referring to Boyd.“For this fuckin’ lunatic?” Sandy said. “I’m gonna shoot him with a Taser shotgun here in a second.”Sandy was hired by the Albuquerque Police Department in 2007, after getting fired from the New Mexico State Police following an ethics investigation for moonlighting at a private security contractor. At the time, the department had faced pressure from the mayor to hire at least 100 more officers, and it began waiving background checks and psychological evaluations for applicants from other agencies. Of 42 Albuquerque police shootings between 2010 and 2014, the Civilian Police Oversight Agency found, 39 percent involved cadets hired between 2007 and 2009. Now, Sandy was one of them.At trial, in September 2016, McGinn seized on these details. “Defendant Sandy was one of the most dangerous kinds of officers you could have on the street, somebody who was out there with something to prove,” she argued. Perez had the misfortune of arriving to the scene as the standoff with Boyd escalated into its final moments. But Sandy, she said, had showed he was determined to shoot Boyd with a Taser shotgun before even seeing him. Sandy was the one who reached for his rifle instead of his Taser shotgun. Sandy was the first to shoot Boyd.In his testimony, Sandy explained that through the magnified scope on his rifle, he noticed several problems. Boyd appeared to stand on higher ground than the field officers who were speaking to him. Sandy was concerned that, if Boyd were to advance on the officers and forced them to back up, the cactuses and rocks would get in the way. “In that terrain, officers are going to be tripping over themselves and trying to navigate the threat posed by Mr. Boyd,” he said. Over the next hour and a half, Sandy continued observing Boyd through his scope and reporting his movements to other officers. As the temperature fell, Boyd bent over to put on a sweatshirt, grabbed his backpack, and began making his way down. “You could tell Mr. Boyd made the decision to come down the mountain,” Sandy said. “But he had also refused to disarm himself or follow commands like ‘Put your knives down, put your hands on your head.’” Moments later, another officer told Sandy, “Bang him.”When he finished his testimony, McGinn stepped up to the podium for cross-examination. “Wasn’t part of your plan to trick Mr. Boyd into coming down so that you could arrest him?”“No ma’am,” Sandy replied.“Didn’t you tell Mr. Boyd, the three of you, to come down the hill?”“Yes ma’am.”“And you didn’t require him, when you asked him to come down the hill, to put down his knives when you asked him to come down?”“Yes ma’am, he was told numerous times, ‘Put down your knives and come down and talk to us,’” Sandy said.McGinn then played a series of five videos recorded on the Taser camera carried by Scott Weimerskirch, one of the officers standing with Sandy in the minutes leading up to the shooting. In each clip, McGinn pointed out, Weimerskirch could be heard telling Boyd to come down the hill. “You never ask him to put down the knives,” she told Sandy.The videos proved, McGinn told the jury, that Boyd held a defensive posture when the officers made their decisions to shoot. “Here’s the thing about physical evidence like video,” she said. “It cannot lie.”In her closing statement, McGinn raised a question on which the outcomes of so many police shooting cases rest: Where do we draw the line between when an officer can shoot someone, and when that shooting constitutes murder? “Society gives police officers a tremendous amount of power,” McGinn said. “We give them a license to kill. You have heard from the witnesses about where the line should be. But it’s not the experts who decide where that line is. It is all of you who decide where that line is.”

The way McGinn saw it, there were two pivotal moments where the shooting could have been avoided. The first was the period of time when Boyd spoke with Mikal Monette, a crisis intervention officer who specialized in negotiating with people with mental illness. On the day of the shooting, Monette was the third officer who arrived at Boyd’s camp. Within 22 minutes of speaking to Boyd, Monette testified, he had stopped taking out his knives and making threats.But after Sandy and other tactical officers arrived, Monette was told to move away from Boyd. Monette later testified that in his five years as a police officer, he had successfully talked down hundreds of people with mental illnesses. Boyd was the only time he had failed.The second pivotal moment began when then-SWAT Sergeant James Fox arrived, 13 minutes prior to the shooting. Fox testified that he first set up a command post at the bottom of the foothills and checked in with officers on the scene. He then began to establish an inner perimeter, and was sending up a beanbag shotgun that had been requested by the officers closest to Boyd. He’d planned to bring in crisis negotiators next. Fox hoped his plan would “slow it down as much as I can.” He didn’t know that Boyd had been ordered to walk down the hill. A SWAT officer with the beanbag shotgun made it halfway up to Boyd when the gunshots went off.“At those two moments, this could have been resolved peacefully,” McGinn said. “The common denominator in both of them was Keith Sandy.”On the day of the shooting, Sandy received a call from a radio dispatcher requesting that a beanbag shotgun be brought to the foothills. A few minutes later, the dispatcher called back to say they had meant to call a different tactical unit but called him by mistake. Sandy, who had just returned from church with his family, told the dispatcher he was already on his way.When he arrived at the foothills, Sandy put on a plated vest and slung a rifle and Taser shotgun over his shoulders. He checked the handgun in his holster and two flash bangs in his pocket. He bantered with a state police officer, asking why he was called to the scene. “What do they got you here for?”“I don’t know,” the other officer replied. “The guy asked for state police,” referring to Boyd.“For this fuckin’ lunatic?” Sandy said. “I’m gonna shoot him with a Taser shotgun here in a second.”Sandy was hired by the Albuquerque Police Department in 2007, after getting fired from the New Mexico State Police following an ethics investigation for moonlighting at a private security contractor. At the time, the department had faced pressure from the mayor to hire at least 100 more officers, and it began waiving background checks and psychological evaluations for applicants from other agencies. Of 42 Albuquerque police shootings between 2010 and 2014, the Civilian Police Oversight Agency found, 39 percent involved cadets hired between 2007 and 2009. Now, Sandy was one of them.At trial, in September 2016, McGinn seized on these details. “Defendant Sandy was one of the most dangerous kinds of officers you could have on the street, somebody who was out there with something to prove,” she argued. Perez had the misfortune of arriving to the scene as the standoff with Boyd escalated into its final moments. But Sandy, she said, had showed he was determined to shoot Boyd with a Taser shotgun before even seeing him. Sandy was the one who reached for his rifle instead of his Taser shotgun. Sandy was the first to shoot Boyd.In his testimony, Sandy explained that through the magnified scope on his rifle, he noticed several problems. Boyd appeared to stand on higher ground than the field officers who were speaking to him. Sandy was concerned that, if Boyd were to advance on the officers and forced them to back up, the cactuses and rocks would get in the way. “In that terrain, officers are going to be tripping over themselves and trying to navigate the threat posed by Mr. Boyd,” he said. Over the next hour and a half, Sandy continued observing Boyd through his scope and reporting his movements to other officers. As the temperature fell, Boyd bent over to put on a sweatshirt, grabbed his backpack, and began making his way down. “You could tell Mr. Boyd made the decision to come down the mountain,” Sandy said. “But he had also refused to disarm himself or follow commands like ‘Put your knives down, put your hands on your head.’” Moments later, another officer told Sandy, “Bang him.”When he finished his testimony, McGinn stepped up to the podium for cross-examination. “Wasn’t part of your plan to trick Mr. Boyd into coming down so that you could arrest him?”“No ma’am,” Sandy replied.“Didn’t you tell Mr. Boyd, the three of you, to come down the hill?”“Yes ma’am.”“And you didn’t require him, when you asked him to come down the hill, to put down his knives when you asked him to come down?”“Yes ma’am, he was told numerous times, ‘Put down your knives and come down and talk to us,’” Sandy said.McGinn then played a series of five videos recorded on the Taser camera carried by Scott Weimerskirch, one of the officers standing with Sandy in the minutes leading up to the shooting. In each clip, McGinn pointed out, Weimerskirch could be heard telling Boyd to come down the hill. “You never ask him to put down the knives,” she told Sandy.The videos proved, McGinn told the jury, that Boyd held a defensive posture when the officers made their decisions to shoot. “Here’s the thing about physical evidence like video,” she said. “It cannot lie.”In her closing statement, McGinn raised a question on which the outcomes of so many police shooting cases rest: Where do we draw the line between when an officer can shoot someone, and when that shooting constitutes murder? “Society gives police officers a tremendous amount of power,” McGinn said. “We give them a license to kill. You have heard from the witnesses about where the line should be. But it’s not the experts who decide where that line is. It is all of you who decide where that line is.” The jurors were asked to consider two main charges: second-degree murder and voluntary manslaughter. Before the jury began their deliberation, Sandy and Perez’s attorneys had asked the judge to dismiss all charges, as often happens at criminal trials, arguing that the prosecutors failed to meet their burden of proof. McGinn could see how voluntary manslaughter, which required proof that the officers were sufficiently provoked, might not apply to Perez; he was not at the scene for most of the standoff. But the judge tossed out voluntary manslaughter for both Perez and Sandy. That left the jurors to decide whether each officer was guilty of second-degree murder — a difficult question to answer in unanimous agreement, even with video and audio recordings and dozens of other pieces of evidence, even with Sandy’s history and the public scrutiny on Albuquerque police.“In order to convict an officer, the jury will be told, as in many criminal cases, they have to decide not just that they think the officer is guilty of committing the crime, but that they are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt,” Sklansky, the Stanford professor, said. “That’s a high burden to satisfy when you’re dealing with situations that are often chaotic, with defendants with whom the jury may sympathize.”On October 11, 2016, after nearly three weeks of trial and 15 hours of deliberation, the jury announced its verdict. For both Sandy and Perez, three jurors voted guilty; nine voted not guilty. The judge declared a mistrial. “Neither side in this case should take any comfort with the verdict,” Pete Dinelli, who previously oversaw the Albuquerque PD as the city’s chief public safety officer, wrote in a Facebook post. Thomas Grover, a former Albuquerque officer and now a lawyer who represents cops, told me, “Basically, Lady Justice said something bad happened that day — it was just a mess. To some degree, everybody lost.”McGinn said there is nothing she would change about the way she presented her case. “But you still can’t see into the hearts of the jurors. When you pick a jury, there are probably already people who will never convict a police officer.” That was the most difficult thing about prosecuting a police shooting: picking a jury that could be fair. “From the moment you pick the jury, you’ve either already lost the case or you still have a chance to lose.”In the weeks leading up to the Boyd trial, more than 850 people received a jury summons. It was one of the biggest jury pools in Albuquerque’s history. Many of the 748 who responded had ties to law enforcement. Some had indicated they lived with a mental illness and asked to be excused. The goal was to find the jurors who, despite extensive media coverage and a widely publicized video, had not yet reached a conclusion about Sandy and Perez’s actions.Among the first 50 jurors who came in for interviews, there were several who were unemployed or had a record of misdemeanor charges — lives that seemed to resemble James Boyd’s more closely than the rest. The defense moved to strike the jurors with prior misdemeanors, arguing that they had failed to indicate their past violations on the form. McGinn and her partners opposed. The judge struck them for cause.

The jurors were asked to consider two main charges: second-degree murder and voluntary manslaughter. Before the jury began their deliberation, Sandy and Perez’s attorneys had asked the judge to dismiss all charges, as often happens at criminal trials, arguing that the prosecutors failed to meet their burden of proof. McGinn could see how voluntary manslaughter, which required proof that the officers were sufficiently provoked, might not apply to Perez; he was not at the scene for most of the standoff. But the judge tossed out voluntary manslaughter for both Perez and Sandy. That left the jurors to decide whether each officer was guilty of second-degree murder — a difficult question to answer in unanimous agreement, even with video and audio recordings and dozens of other pieces of evidence, even with Sandy’s history and the public scrutiny on Albuquerque police.“In order to convict an officer, the jury will be told, as in many criminal cases, they have to decide not just that they think the officer is guilty of committing the crime, but that they are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt,” Sklansky, the Stanford professor, said. “That’s a high burden to satisfy when you’re dealing with situations that are often chaotic, with defendants with whom the jury may sympathize.”On October 11, 2016, after nearly three weeks of trial and 15 hours of deliberation, the jury announced its verdict. For both Sandy and Perez, three jurors voted guilty; nine voted not guilty. The judge declared a mistrial. “Neither side in this case should take any comfort with the verdict,” Pete Dinelli, who previously oversaw the Albuquerque PD as the city’s chief public safety officer, wrote in a Facebook post. Thomas Grover, a former Albuquerque officer and now a lawyer who represents cops, told me, “Basically, Lady Justice said something bad happened that day — it was just a mess. To some degree, everybody lost.”McGinn said there is nothing she would change about the way she presented her case. “But you still can’t see into the hearts of the jurors. When you pick a jury, there are probably already people who will never convict a police officer.” That was the most difficult thing about prosecuting a police shooting: picking a jury that could be fair. “From the moment you pick the jury, you’ve either already lost the case or you still have a chance to lose.”In the weeks leading up to the Boyd trial, more than 850 people received a jury summons. It was one of the biggest jury pools in Albuquerque’s history. Many of the 748 who responded had ties to law enforcement. Some had indicated they lived with a mental illness and asked to be excused. The goal was to find the jurors who, despite extensive media coverage and a widely publicized video, had not yet reached a conclusion about Sandy and Perez’s actions.Among the first 50 jurors who came in for interviews, there were several who were unemployed or had a record of misdemeanor charges — lives that seemed to resemble James Boyd’s more closely than the rest. The defense moved to strike the jurors with prior misdemeanors, arguing that they had failed to indicate their past violations on the form. McGinn and her partners opposed. The judge struck them for cause.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

With an outsider like McGinn stepping in, there was suddenly the possibility, however remote, that two cops might be punished for shooting a man to death. In the past two years since Ferguson, special prosecutors have been appointed to investigate the high-profile police shootings of Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Isaac Holmes in St. Louis, and Philando Castile in Minneapolis, among others. The failure of Baltimore’s state’s attorney, Marilyn Mosby, to convict six police officers implicated in the April 2015 death of Freddie Gray renewed calls to appoint a special prosecutor in criminal cases involving cops.But appointing a special prosecutor does not change the overwhelming odds against winning a conviction, David Sklansky, a Stanford University law professor who writes about police investigations, explained. “It is unusual for there to be a criminal prosecution in these cases, and it’s highly unusual for a private attorney to be brought in to prosecute the case. These are difficult cases to prosecute because they involve tactical and split-second decisions by officers that jurors are very reluctant to second-guess. The critical question in most cases of this kind will be the officer’s state of mind.”A few months after McGinn took over the case, Boyd’s family won a $5 million settlement in their wrongful death lawsuit against the city of Albuquerque. But convincing a jury to convict two police officers would be a long shot. “From early on, this was an unwinnable trial,” Samson Costales, who retired from the Albuquerque PD in 2001, told me. “This is New Mexico. There’s no way there’d be a unanimous decision by all 12 of those jurors.” Still, Costales, who previously hired McGinn and won a $662,000 settlement against the department over alleged defamation and retaliation, felt McGinn was the best person for the job. “If anyone could, in fact, get a conviction, it would be her.”No Albuquerque police officer had been charged for a fatal shooting in at least 50 years.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

In 1990, McGinn won her first big settlement against the Albuquerque Police Department, after cops shot and injured an unarmed black man named Jimmy Hill. She won another case in 1996, this time involving the fatal police shooting of a 33-year-old suicidal man named Larry Harper. After the settlement, she heard that the SWAT team had pinned her photo to a piñata and took turns whacking it.In 2014, McGinn represented the family of Christopher Torres, a 27-year-old with schizophrenia who was fatally shot in the back while while being held to the ground by two officers in his own backyard, in his pajamas, unarmed. McGinn and her partner met with Brandenburg several times, offering evidence they believed warranted criminal charges. The charges never came, but the Torres family later won a $6 million civil settlement from the city.“If someone is abusing the law, it teaches you where to throw the wrench to gum up the works and keep the judicial steamroller from crushing your client.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

The attorneys defending Sandy and Perez centered their arguments on Boyd’s threats and his past record of assaulting cops. They argued that Sandy and Perez had reason to fear for their lives and the lives of fellow officers, that the courtroom was not the place to address how a city should deal with its mentally ill or its police department. “It doesn’t matter that he made a mistake,” Sam Bregman, Sandy’s attorney, said as he closed. “It doesn’t matter that there were 19 officers. It doesn’t matter how many bullets they had on them, what type of guns they had on them. What matters is the perception of these two men, based on their training, based on the orders they are required to follow.” If cops were subject to prosecution for following their training, he asked, “who would ever want to be a police officer?”“Here’s the thing about physical evidence like video. It cannot lie.”

Advertisement

As the trial came to a close, McGinn looked around the courtroom. Several rows of people sat behind the officers. On McGinn’s side of the room, a more sporadic crowd had trickled in and out, including the family members of Boyd and Christopher Torres. Occasionally, a small number of men and women filled the back row. At one point a man in ragged clothes handed McGinn a fistful of hard candy. But on the day of her closing argument, hardly anyone was there.“I felt an overwhelming sadness that day,” McGinn told me. “At all levels, we had failed James Boyd as a society.”Many of the 19 officers who were at the Boyd shooting have since left the department. Sandy retired in November 2014, eight months after the shooting. Perez, who was fired after the shooting, asked to return to the department the day after the verdict.It is unlikely, but still possible, that Sandy and Perez will be retried. McGinn has said she will leave the decision up to Brandenburg, whose term ends in January, and her presumptive successor, Raúl Torrez. Several people I interviewed for this story have suggested that, in light of the Boyd case and heightened national attention, new charges could be filed in a number of other police shooting cases in Albuquerque. At the center of one case is Mary Hawkes, a 19-year-old who was allegedly shot and killed while running away from a police officer. But like so many police shooting cases, there’s no guarantee that charges, much less a conviction, will come.When I met McGinn in Albuquerque the week after the verdict, she was preparing for her next trial. Her latest client is a woman who was struck by a car while riding her bike across a wide intersection. I asked McGinn whether she would ever prosecute another police shooting. “Not this year, I wouldn’t do it,” she said, letting out a laugh. She paused. “Look, if justice needs me at some point again, I wouldn’t turn it down. Hopefully this situation will never happen again. Hopefully people see you can present the case and fight it to a draw and that’s OK. A prosecutor’s job is to tell the story of the dead in hopes that it will help the living.” In a sense, she felt, that was all she could do.Jaeah Lee is a writer in San Francisco. She was most recently a staff reporter at Mother Jones, covering policing after Ferguson. Her work has been featured in the Atlantic, the Guardian, Pop Up Magazine, Democracy Now, and other outlets. Follow her on Twitter @jaeahjlee.“Basically, Lady Justice said something bad happened that day — it was just a mess. To some degree, everybody lost.”