LEXINGTON, Kentucky — Mya Slone had a secret. The 26-year-old mother of two was pregnant again, but that was obvious — at 34 weeks along, her belly was bulging beneath a dark pink top. Standing on her front porch in rural Kentucky, surrounded by soybean fields and rose bushes that had wilted in the late July heat, she pulled out a pack of Marlboros. Smoking wasn’t the only thing she was trying to quit.

Slone was taking medication — the drug buprenorphine — to help with her recovery from addiction to painkillers and heroin. She’d almost lost her kids because of her drug use, but now that she was expecting another, she had a choice: Go cold turkey and risk a relapse, or continue taking the medication that helped turn her life around. The catch was that buprenorphine, known as Suboxone or Subutex, is an opioid just like heroin. The drug would ease her cravings, but it could also cause her baby, a girl she planned to call Emma Grace, to be born addicted and go into withdrawal.

“I don’t want her to have to go through that,” said Slone, who has long blonde hair and tattoos on her shoulders and feet. “Compare the withdrawal symptoms for us and infants, the symptoms are relatively the same. They’ll just be ten times harder on her.”

Her fiancé, who was also recovering from heroin addiction, knew about the Subutex. Her doctor prescribed it, and they agreed that taking it was the right decision. But she was still hiding it from others, including her future in-laws. She was worried what people would think, but ultimately, as she put it, “It’s better to be on this than strung out on heroin or pain pills or something else.”

With the United States in the midst of an unprecedented opioid epidemic, pregnant women all over the country are in similar situations. Help for pregnant women struggling with addiction can be hard to come by. In many areas, the stigma that surrounds medication-assisted treatment is double for expectant mothers, since they are seen as being responsible for two lives. Seeking drug treatment often leads to situations that exacerbate feelings of guilt and shame. Kids can be taken away. Moms can end up behind bars.

“You go to Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia — they’re building special hospital units for these kids.”

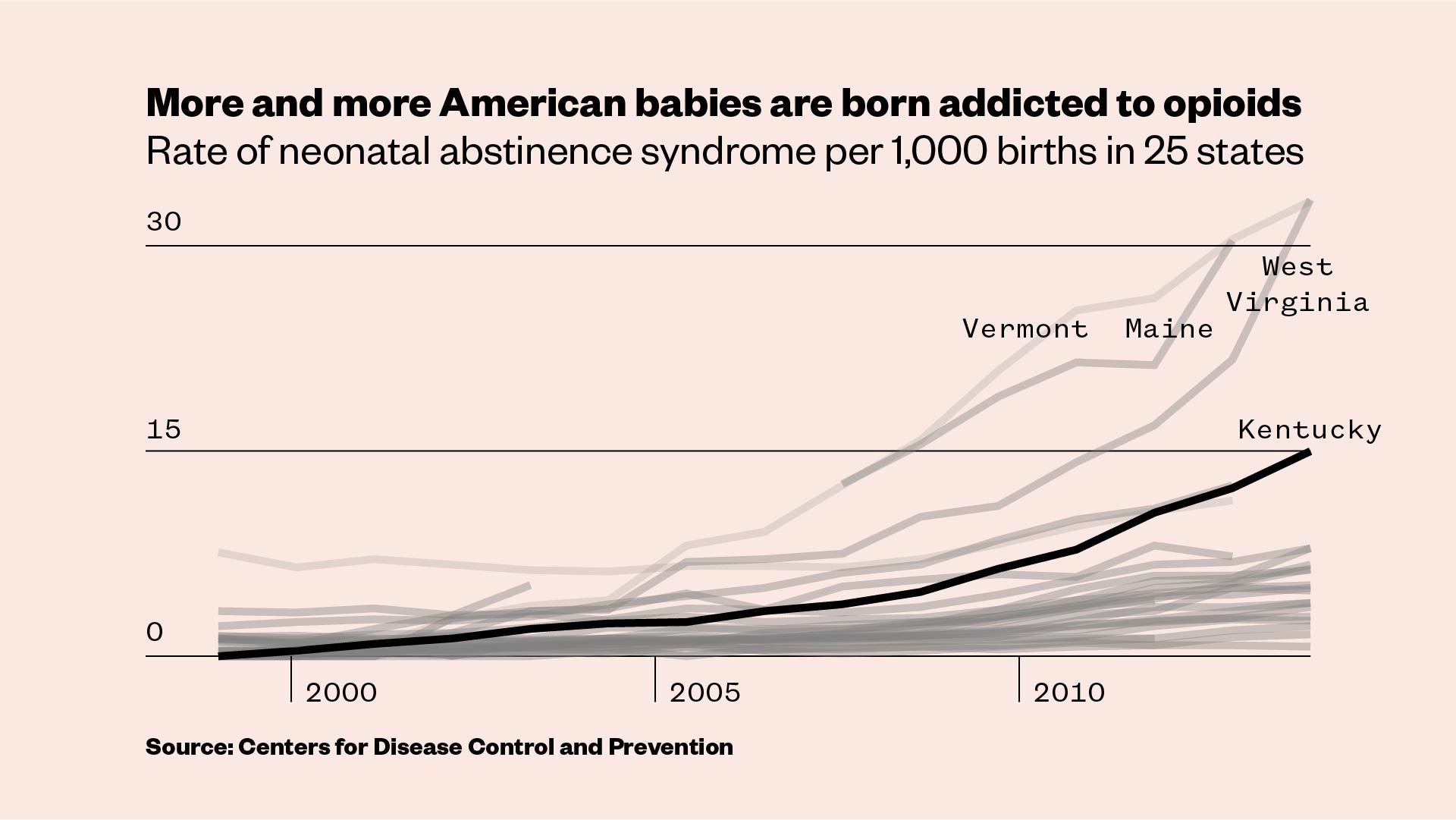

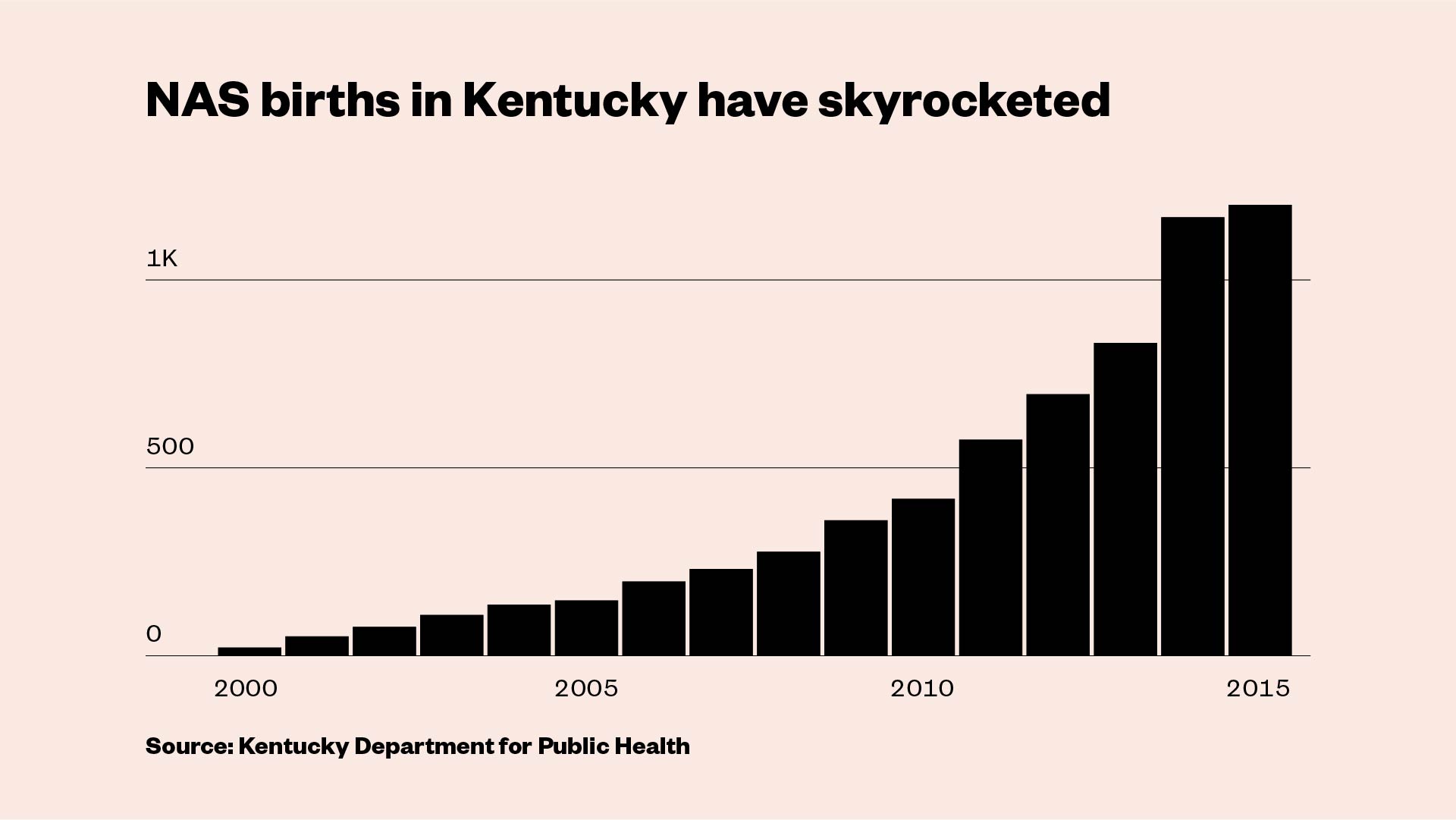

The staggering rise of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, or NAS, the medical term for babies who experience withdrawal, has overwhelmed the medical system, and many intensive care units for newborns are at capacity. The rate of NAS has soared by 400 percent nationally since 2000. One baby is born with the syndrome every 25 minutes. It’s especially grim in Kentucky, where one out of every 50 newborns has NAS.

“You go to Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia — they’re building special hospital units for these kids,” said Matthew Grossman, a pediatrician at Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital and a Yale Medical School professor. “It’s become a major, major issue.”

Slone was lucky enough to find a program — one of only a handful nationwide — that’s shifting the paradigm. Her program, called PATHways, is essentially a one-stop shop for pregnant women in recovery, offering counseling, medication-assisted treatment, prenatal care, and parenting classes. Created in 2014 by an all-female team of four doctors and nurses affiliated with the University of Kentucky’s healthcare system, it’s also using new approaches to NAS that shorten hospital stays for infants and empower mothers. The results have been impressive: More than 190 women have participated since it launched, and only once has a mother tested positive for illicit opioids at her child’s birth.

It’s the type of care that every woman in Slone’s shoes deserves. And if it becomes the norm, it could help break the cycle of addiction.

The opioid epidemic has not spared women and babies. Heroin overdose deaths among women have tripled in recent years, and research has shown that women are more likely to be prescribed painkillers at higher doses and for longer periods than men are. Pill overdoses among women have surged more than 400 percent since 1999, nearly double the rate among men.

Agatha Critchfield, a Lexington native, cofounded PATHways (the acronym stands for Perinatal Assistance and Treatment Home) after returning to her hometown from medical school and training. While she was away, the rate of opioid addiction — and the number of babies born with NAS — skyrocketed, especially in rural Appalachian parts of Kentucky. In 2000, only 19 babies in the state were born with NAS; by 2015, there were 1,060.

“This is where this crisis has hit hardest, or at least hit first,” said Critchfield, a specialist in high-risk obstetrics. “I went from an urban area to a rural area and I was like, whoa, what’s going on here? I’d never been in a situation where a majority of my patients had addictions.”

The small team of PATHways doctors, nurses, and counselors shares space at a tiny clinic in the heart of Lexington. Medication-assisted treatment is key to the program. A doctor on staff prescribes the medication, usually Subutex, and the women must check in every week, at which point they also get a medical checkup and counseling. Buprenorphine dramatically reduces the risk of relapse and it’s much safer for both the mother and baby than using illicit opioids, which can be laced with fentanyl, the powerful drug that’s responsible for a growing number of overdoses. There hasn’t been a single fatal overdose among the women at PATHways.

Another upshot of medication-assisted treatment is that it reduces the chances of NAS. But it doesn’t eliminate the risk entirely. If a woman from PATHways has a baby born with the syndrome, they end up at Kentucky Children’s Hospital, a few miles away from the small clinic. NAS babies are typically placed in the neonatal intensive care unit, or NICU. Lori Shook, a neonatologist involved with PATHways, called it “the worst place in the world to take a baby that is going through withdrawals.”

In the NICU, doctors, nurses, and parents speak in hushed voices, trying not to disturb the tiny newborns encased in plastic chambers. Tubes snake out of the enclosures, connecting to machines that beep and hum. Alarms blare. When one baby cries, it triggers a chorus of wails.

NAS babies typically start to show symptoms a day or two after birth. Much like adults experiencing withdrawal, they tend to be extremely irritable. They cry relentlessly, wake up easily, and refuse to eat. They have vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, sweating, tremors, sneezing, congestion, and fevers. They can die from dehydration or other complications, though fatalities are extremely rare in a hospital setting.

Not much is known about the long-term health repercussions of in utero exposure to opioids. There are some indications that it could be linked to shorter attention spans and reduced social engagement in toddlers, along with negative effects on cognitive abilities and motor skills in later years. The current generation has, sadly, provided a larger sample size to study, and research is ongoing.

For decades, dating back to the late 1970s, doctors have mostly treated NAS babies with the same protocol. The infants are “scored” on a scale that assigns numeric values to NAS symptoms. If a newborn whose mother was on opioids scores high, the baby is placed in the NICU, given methadone or morphine, and gradually weaned off the drugs over a few weeks.

Rather than separating newborns from their mothers, Shook and others doctors are now keeping them together and naturally soothing the babies’ NAS symptoms with swaddling, breastfeeding, aromatherapy, massage, and Jin Shin Jyutsu, a Japanese technique that’s like acupuncture but with gentle hand pressure instead of needles. Opioids are used only as a last resort when the baby doesn’t calm down.

“They completely left the mother out of the equation as a person to provide care,” Shook said, referring to the traditional approach to NAS. “The real key to babies doing well is being with their mothers. We’re empowering them rather than taking their babies away.”

Shook asked a massage therapist on her staff to demonstrate how to comfort a baby without medication. The masseuse picked up a 4-day-old whose mother was on Subutex. The boy had long spindly legs and thick brown hair. His parents had left the room and he howled until the therapist laid the baby on her lap, put a few dabs of grapeseed oil on her gloves, and gently rubbed his feet, hands, and torso. In minutes, he stopped crying and a pacifier fell from his lips in quiet bliss. She said his body felt “like a melted stick of butter.”

Shook’s holistic approach has produced astounding results. The average length of stay for NAS babies in her NICU has decreased from 29 days to six, and 97 percent of the babies who stay with their mothers during treatment require no opioid medications.

Grossman, the Yale doctor, has had similar success using a model called “Eat, Sleep, Console” or ESC, which keeps mothers “rooming-in” with NAS newborns virtually 24/7 and encourages them to do normal mom things like feed and gently rock their babies to sleep. Infants with NAS used to spend an average of 22 days in his hospital’s NICU; now they’re usually discharged after six days and rarely require opioids.

Hospitals are starting to adjust to these methods, but change is slow. Traditionalists are still medicating babies and keeping them in intensive care. Beyond shifting attitudes toward treating NAS babies, Shook says we need to treat their mothers differently too.

“So many of these women have never been listened to. They’ve been talked down to and abused.”

Drug use during pregnancy has been prosecuted as criminal child abuse in Alabama and South Carolina, and 24 states consider it to be child abuse under civil child-welfare laws. Tennessee lawmakers passed a “fetal assault” law in 2014 that made it a felony for women to use drugs while pregnant, and at least 100 people were prosecuted before the measure was taken off the books last year. Other programs have offered reduced jail time or even cash payments to women with addiction problems who agree to be sterilized.

Shook recoiled at how harshly pregnant women with addiction problems were treated at hospitals when she began her career in the late ’70s. Now, she said, “more nurses are looking at moms as a person with a disease and not a loser mom who can’t do the right thing,” but that attitude can still be found.

“So many of these women have never been listened to,” Shook said. “They’ve been talked down to and abused. All we do is stomp on ’em some more, and that’s wrong.”

Back at the PATHways clinic, several pregnant women huddled in the parking lot outside, taking a cigarette break after a group therapy session. Slone stood in the shade of a small tree, smoking another Marlboro. She’d been warned that nicotine can cause NAS too, and the program offers classes to help quit, but it wasn’t her primary concern.

“This doesn’t help, I know it doesn’t,” she said, “but I have to do one thing at a time.”

That one thing — getting off opioids entirely — doesn’t happen overnight. Slone had been on buprenorphine for nearly four years, which is longer than typical. The goal was to gradually lower her dosage, but not until after the baby came. In the meantime, she was focused on attending counseling. She’d found previous drug treatment programs to be “super, super judgmental,” but said it helped to be around women in similar situations at PATHways.

Slone became addicted to opioids a few months after the birth of her first child, a daughter, in 2010. The “turning point,” she said, came when she got pregnant with her son three years later.

She was determined to get clean, but fears about losing her baby to the foster system caused her to skip out on prenatal care for months. Her insurance at the time wouldn’t cover treatment, so she ended up buying buprenorphine from a dealer instead.

Her son was born underweight, and though he didn’t have NAS, the positive drug screen for opioids caused by the buprenorphine led to a meeting with the state social services agency. Slone was nervous, but she was ultimately allowed to keep the boy, and she now splits custody with his father, along with helping to raise her fiancé’s two kids. She also works as an assistant manager at a clothing store. She credits buprenorphine for her turnaround.

“I’m a better person now than I was four years ago,” she said. “I was stealing and all kinds of dumb shit. I couldn’t keep a job. I was looking for dope all the time.”

One PATHways therapy session, led by Jason Joy, a counselor with a personality to match his name, was intense. A young pregnant woman described relapsing on heroin the week before. She wept and called herself “a fuck-up” before Joy intervened.

“Guess what,” he said. “We don’t invest in fuck-ups around here. We invest in people who are worth it, and you are worth it.”

For some women, having a baby can be a transformative event after years of abuse, addiction, and incarceration. But giving birth doesn’t wipe the slate clean, and it can be an overwhelming struggle to be a new mother, stay sober, and navigate the bureaucracy of state social services or the criminal justice system.

“At the end of the day, it’s about not creating another generation of this.”

Joy estimates that a little over half of the moms in PATHways get to keep their babies, but the goal is not necessarily to hit 100 percent. The responsibilities of parenting can be too much to handle for some women who are still struggling to break free of their addictions, he explained.

“There are some who need to have recovery be first and foremost,” Joy said. “At the end of the day, it’s about not creating another generation of this.”

When PATHways first started, it was funded by a grant from the Center for Medicaid Services, which only covered up to eight weeks of postpartum care. Kristin Ashford, another PATHways cofounder and a professor at the UK College of Nursing, said they quickly realized that wasn’t enough.

“All these moms were relapsing,” she said. “Between three and six months is when they need the most support. They have the highest depression symptoms and the highest levels of stress.”

Ashford went “begging and knocking on doors for money” to cover up to two years of services, which they’ve dubbed the “beyond birth” phase. They’re currently working to expand, and Critchfield wants to create a “hub and spoke” network, where the program partners with clinics around Kentucky to ease the burden on women from rural areas. She’s also fielded several inquiries from interested groups in other states, and in the long term, she’d like to see the PATHways model spread across the country.

Similar programs already exist in Vermont and North Carolina, but most women like Slone have few options. In her community, which she joked is so small it “doesn’t even have a Walmart,” there’s nothing that offers specialized care for pregnant women with addiction issues, and the places she could go are abstinence-only, which means buprenorphine isn’t allowed. “If you’re not completely clean, they don’t want to hear from you,” she said.

It’s more than an hour’s drive from Slone’s house to PATHways, but without the program, her pregnancy may have ended up like her last one, with her forgoing prenatal care and being left to fend for herself. The regular medical checkups ended up being crucial.

In August, ultrasounds showed that her baby was on track to be slightly underweight — which is an indicator for NAS. Then doctors noticed another potential complication, which she was told could require surgery immediately after birth and a lengthy stay in the NICU. Slone was prepared for NAS, but this was something different. She checked into the hospital expecting to be induced into labor and fearing the worst.

On Aug. 25 at 5:20 a.m., Slone’s daughter, Emma Grace, arrived. She was small — 5 pounds, 12 ounces — and she had complications that required monitoring and placement in the NICU, but no surgery. She was diagnosed with NAS, though Shook, the neonatologist, suspects the baby may have just been showing symptoms because of her other health problems. Slone expected to be closely involved in the NAS treatment and provide the intensive mothering that Shook prefers, but the complex medical situation didn’t allow it.

With space at the hospital limited, Slone was discharged while her daughter remained in the NICU. The overall prognosis is good, but Slone was left frustrated, scared, and sleeping in her car in the hospital parking lot in order to stay close. Because of the NAS diagnosis, social services also got involved, adding another layer of stress to the already tense situation. She’s confident she’ll be able to keep the baby, but she still doesn’t know for sure. Still, the complications and uncertainty haven’t changed Slone’s advice for other pregnant women recovering from addiction.

“Don’t be afraid to seek help,” she said. “Don’t be worried about what other people think.”

Keegan Hamilton is U.S. editor for VICE News.

Need help with opioid addiction? Find a treatment center near you or find a doctor in your area who offers medication-assisted treatment.