When the average American gets arrested, they can expect that within a few days they’ll appear before a judge for a bond hearing, which determines whether they will stay in jail until they have their day in court. For immigrants, the rules are different. In all but two federal jurisdictions, they can be detained for months — sometimes years — without receiving a shot at freedom.On Tuesday, the Supreme Court reheard arguments in Jennings v. Rodriguez, a case that could force the government to give immigrants a bond hearing within a certain number of days after they are detained. The stakes are high: A ruling that preserves the status quo would help the Trump administration accomplish its goal of deporting as many people as possible, while establishing a new protocol would make it slightly easier for a person to fight to stay in the country.The Supreme Court first heard arguments in the case last November, before the arrival of Justice Neil Gorsuch, and decided to order a redo before the full nine-member court. This time around, the question of whether immigrants can be indefinitely detained provoked some animated responses from the justices.Assistant Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart, representing the Trump administration, tried to make the case that “aliens at the threshold have no constitutional rights under due process clause,” a reference to a passage from the Fifth Amendment that says the government isn’t allowed to hold people without giving them the chance to defend themselves in court. Justice Stephen Breyer wasn’t buying the argument, and he got worked up, at least by Supreme Court standards, pointing out that even heinous criminals are entitled to receive prompt bond hearings.Part of the case against indefinite detention is that it pressures people to accept deportation — aka “voluntary departure” — because people eventually decide they would rather be sent back to their homeland than languish for months behind bars. It also makes it harder for asylum seekers, green card holders, and others with compelling claims to hire an attorney or gather evidence because they’re locked up, often in remote detention centers operated by private prison contractors.The plaintiff in the Supreme Court case is Alejandro Rodriguez, a lawful permanent resident who came to the U.S. as an infant. He was working as a dental assistant in California when he was detained by the Department of Homeland Security and placed in deportation proceedings because he’d previously been convicted of misdemeanor drug possession and “joyriding.” He was held for more than three years while he fought to stay in the country. During that stretch, his pregnant U.S.-citizen wife was forced to go on welfare, and he missed the birth of their daughter.Rodriguez’s case became a class-action lawsuit against the government, involving hundreds of other immigrants who were also held for lengthy periods while their cases worked their way through the system. They eventually won a favorable ruling in 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which now requires immigrants detained in California and other Western states receive a bond hearing within six months. ACLU attorney Ahilan Arulanantham argued Tuesday that the six-month rule isn’t perfect, “but you have to draw the line somewhere.” The ACLU previously noted that immigrants like those in the Rodriguez lawsuit are five times more likely to win their case than the typical detainee because they’re able to gather evidence and hire lawyers while they’re free on bond, which is granted to roughly 70 percent of them.Outside of California and a handful of states in the Northeast, including New York, decisions about whether to grant temporary freedom to immigrants fighting deportation are left to Homeland Security officials. The ACLU has said this process involves “checking a box on a form that contains no specific explanation and reflects no deliberation,” and notes that “there is no hearing, no record, and no appeal.”In a previous case, the government told the Supreme Court that the average detention time for immigrants was only about a month and a half “in the vast majority of cases” and five months in cases involving appeals. Upon further review, it turned out that most immigrants in the Rodriguez lawsuit were detained for more than 13 months, with 20 percent held for at least 18 months, and 10 percent for two years or more.

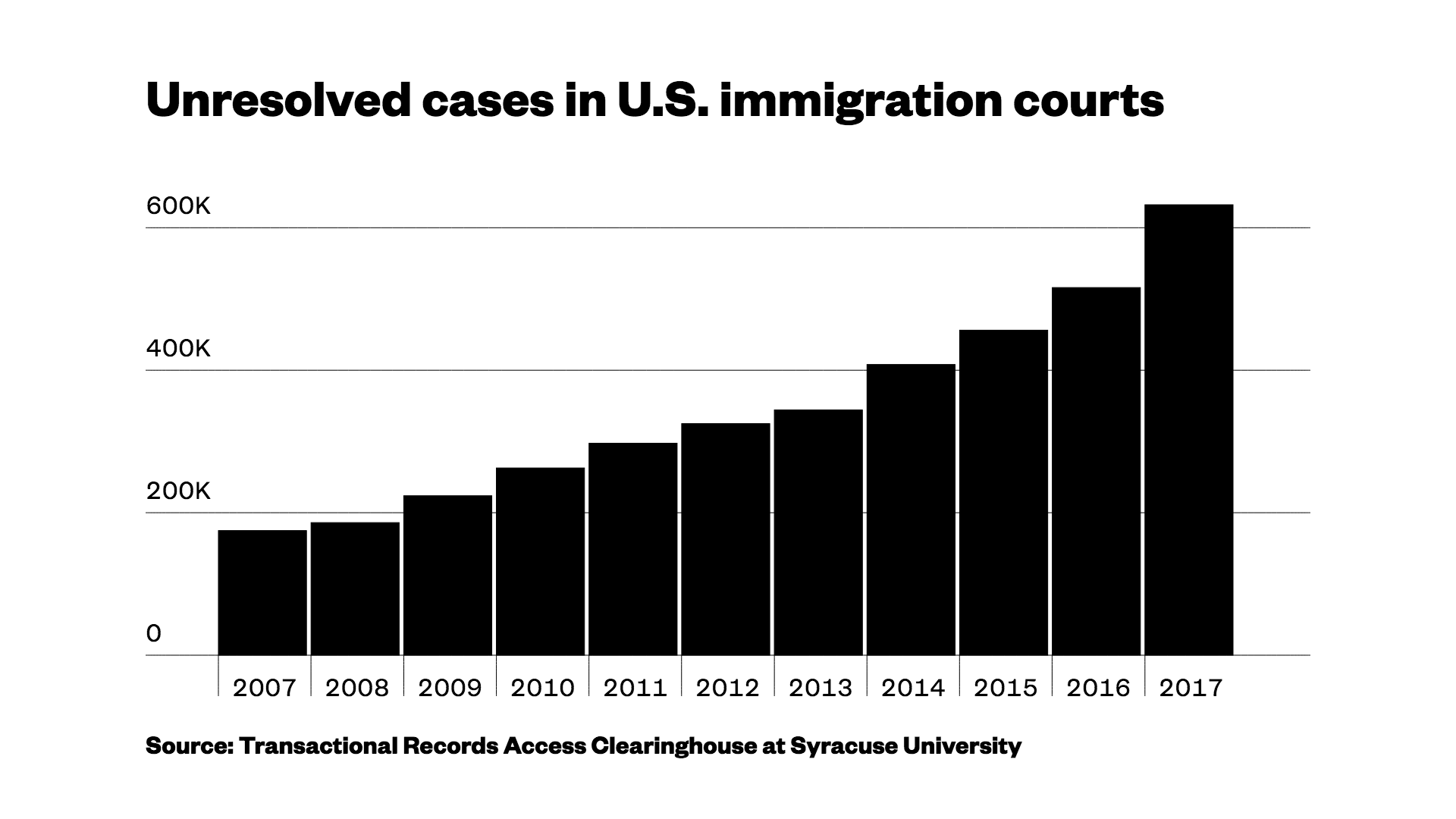

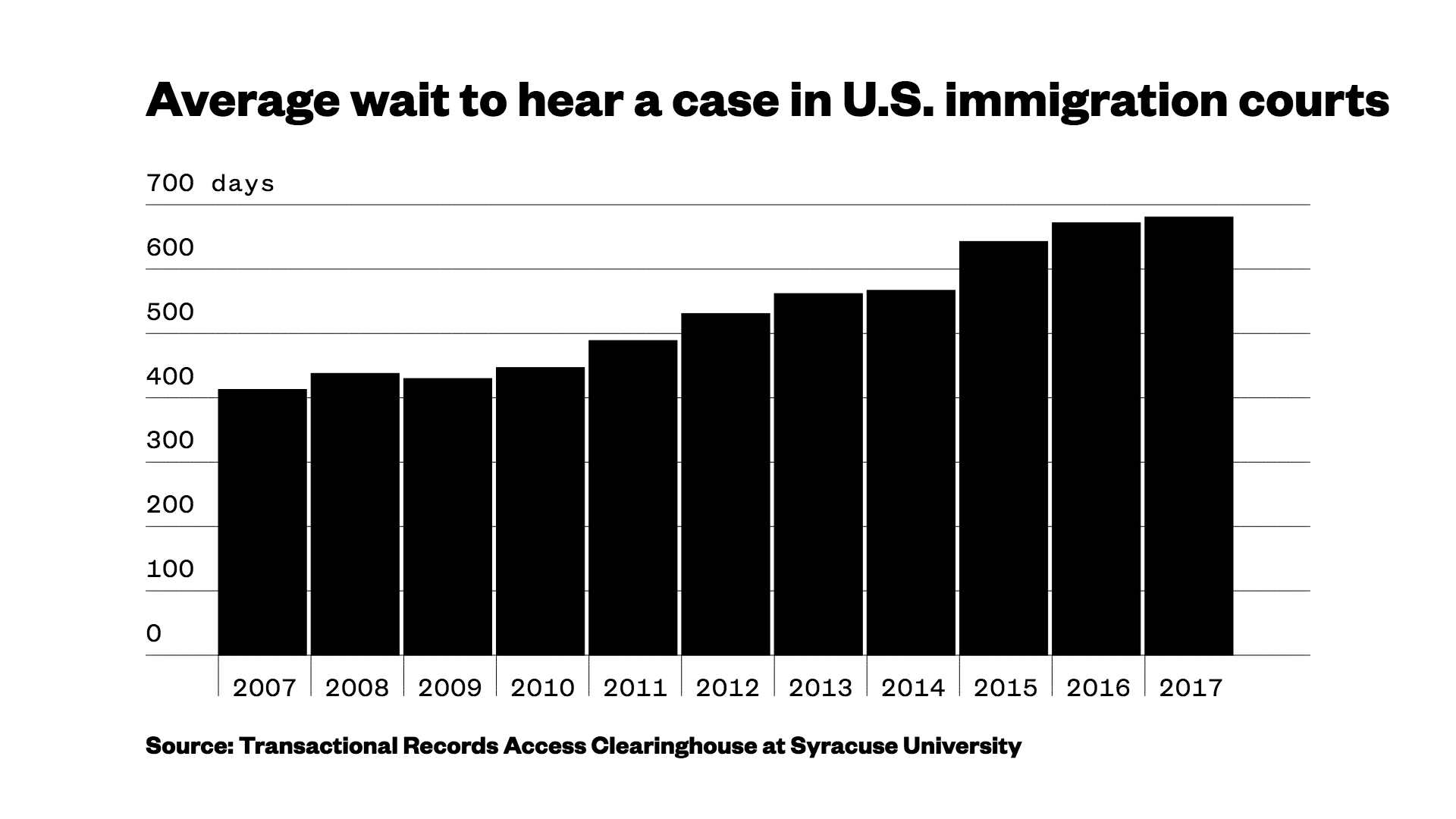

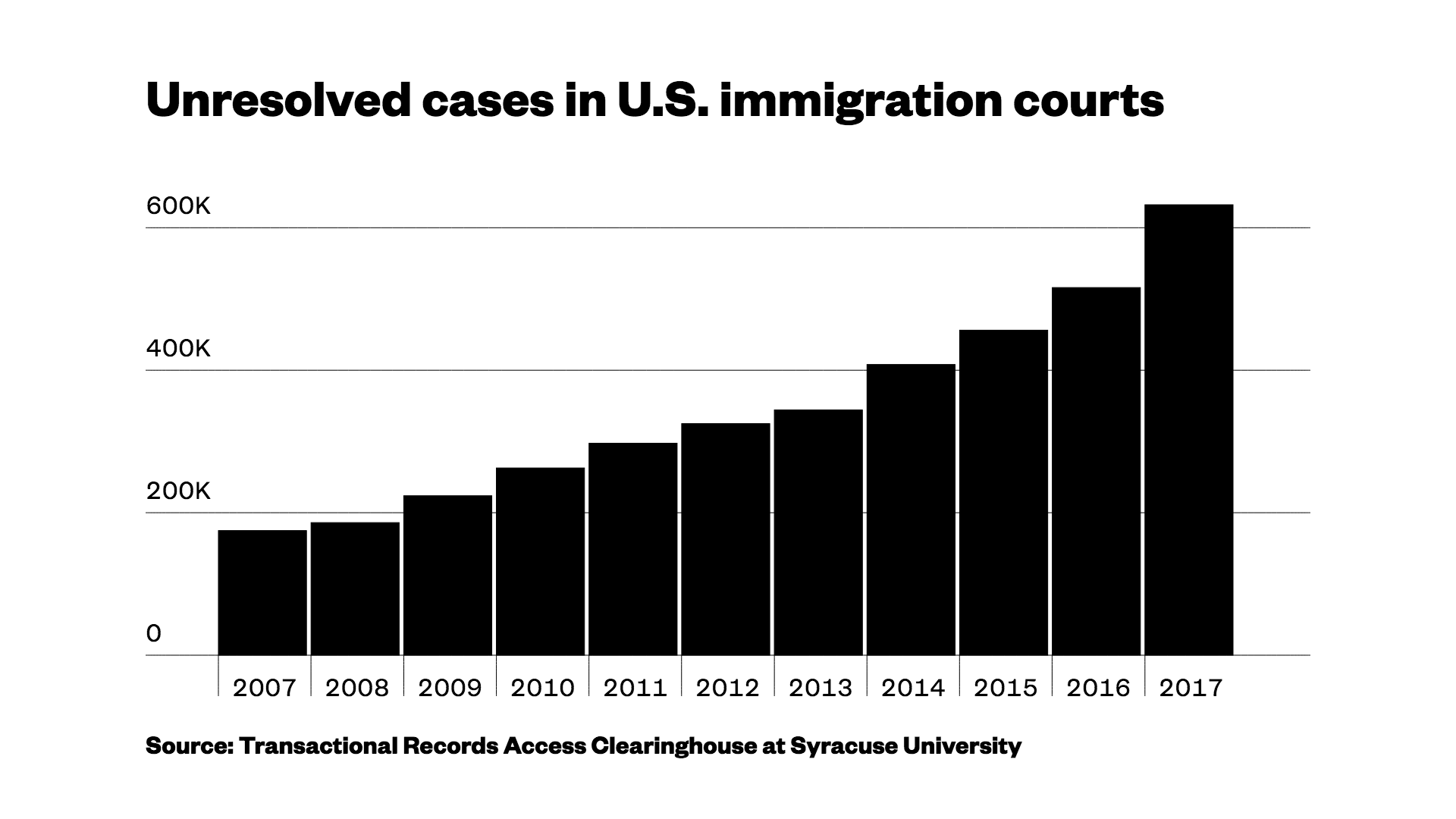

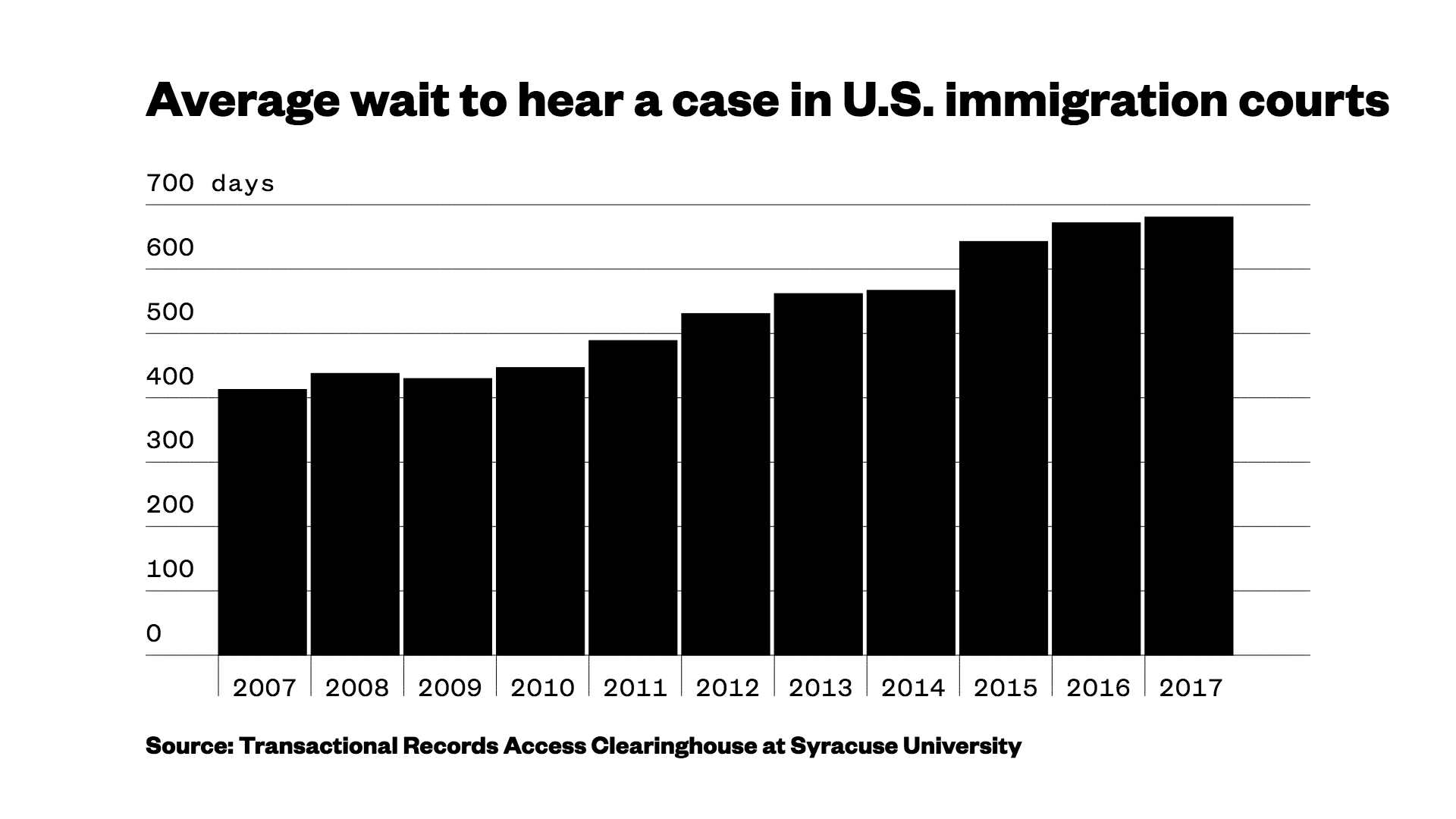

ACLU attorney Ahilan Arulanantham argued Tuesday that the six-month rule isn’t perfect, “but you have to draw the line somewhere.” The ACLU previously noted that immigrants like those in the Rodriguez lawsuit are five times more likely to win their case than the typical detainee because they’re able to gather evidence and hire lawyers while they’re free on bond, which is granted to roughly 70 percent of them.Outside of California and a handful of states in the Northeast, including New York, decisions about whether to grant temporary freedom to immigrants fighting deportation are left to Homeland Security officials. The ACLU has said this process involves “checking a box on a form that contains no specific explanation and reflects no deliberation,” and notes that “there is no hearing, no record, and no appeal.”In a previous case, the government told the Supreme Court that the average detention time for immigrants was only about a month and a half “in the vast majority of cases” and five months in cases involving appeals. Upon further review, it turned out that most immigrants in the Rodriguez lawsuit were detained for more than 13 months, with 20 percent held for at least 18 months, and 10 percent for two years or more. The wait times are growing, too. There’s currently a backlog of more than 632,000 unresolved immigration cases, and the average case has been pending for 681 days, up from 413 days a decade ago. Justice Elena Kagan mentioned the backlog Tuesday, asking Stewart, “And are you suggesting that if the backlog is five years, it’s okay to keep them there for five years without a determination of whether they pose any risk of flight or whether they’re dangerous? ”That’s essentially the question the Supreme Court will now decide. A ruling is expected later this year.

The wait times are growing, too. There’s currently a backlog of more than 632,000 unresolved immigration cases, and the average case has been pending for 681 days, up from 413 days a decade ago. Justice Elena Kagan mentioned the backlog Tuesday, asking Stewart, “And are you suggesting that if the backlog is five years, it’s okay to keep them there for five years without a determination of whether they pose any risk of flight or whether they’re dangerous? ”That’s essentially the question the Supreme Court will now decide. A ruling is expected later this year.

Advertisement

“Normally, if you were to detain somebody… you would give them a bail hearing,” Breyer said. “Why is it different here? We give triple axe murderers … bail hearings. Are they dangerous? Are they a risk of flight?”Breyer then apologized for raising his voice but added that immigrants “are just as much people.”Stewart later claimed that certain immigrants “have no constitutional right to be admitted into the country,” and said that if they don’t like being indefinitely detained, “that alien always has the option of terminating the detention by accepting a final order of removal and returning home.”“Why is the statute different here? We give triple axe murderers … bail hearings. Are they dangerous? Are they risk of flight?”

Advertisement

Advertisement