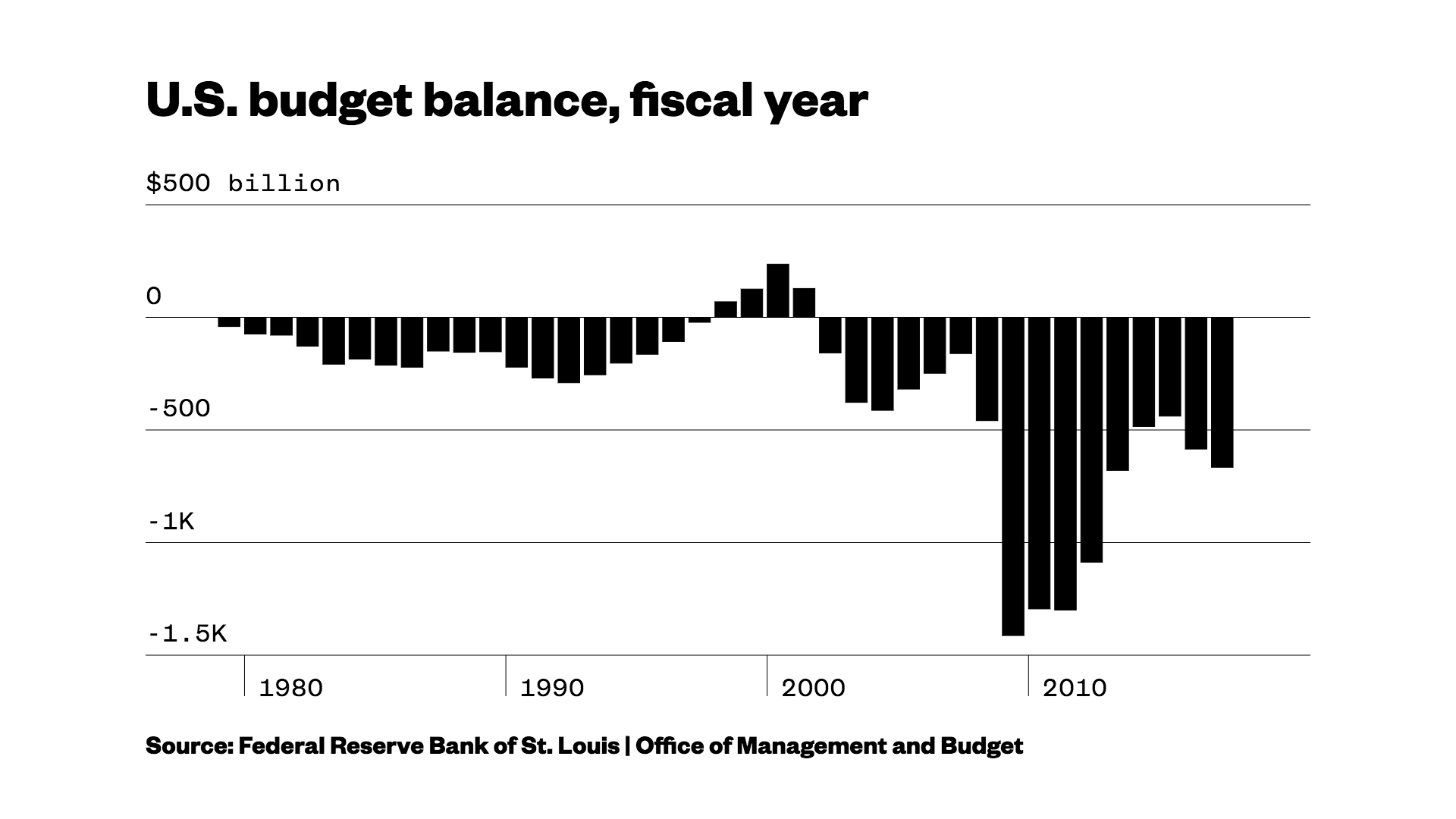

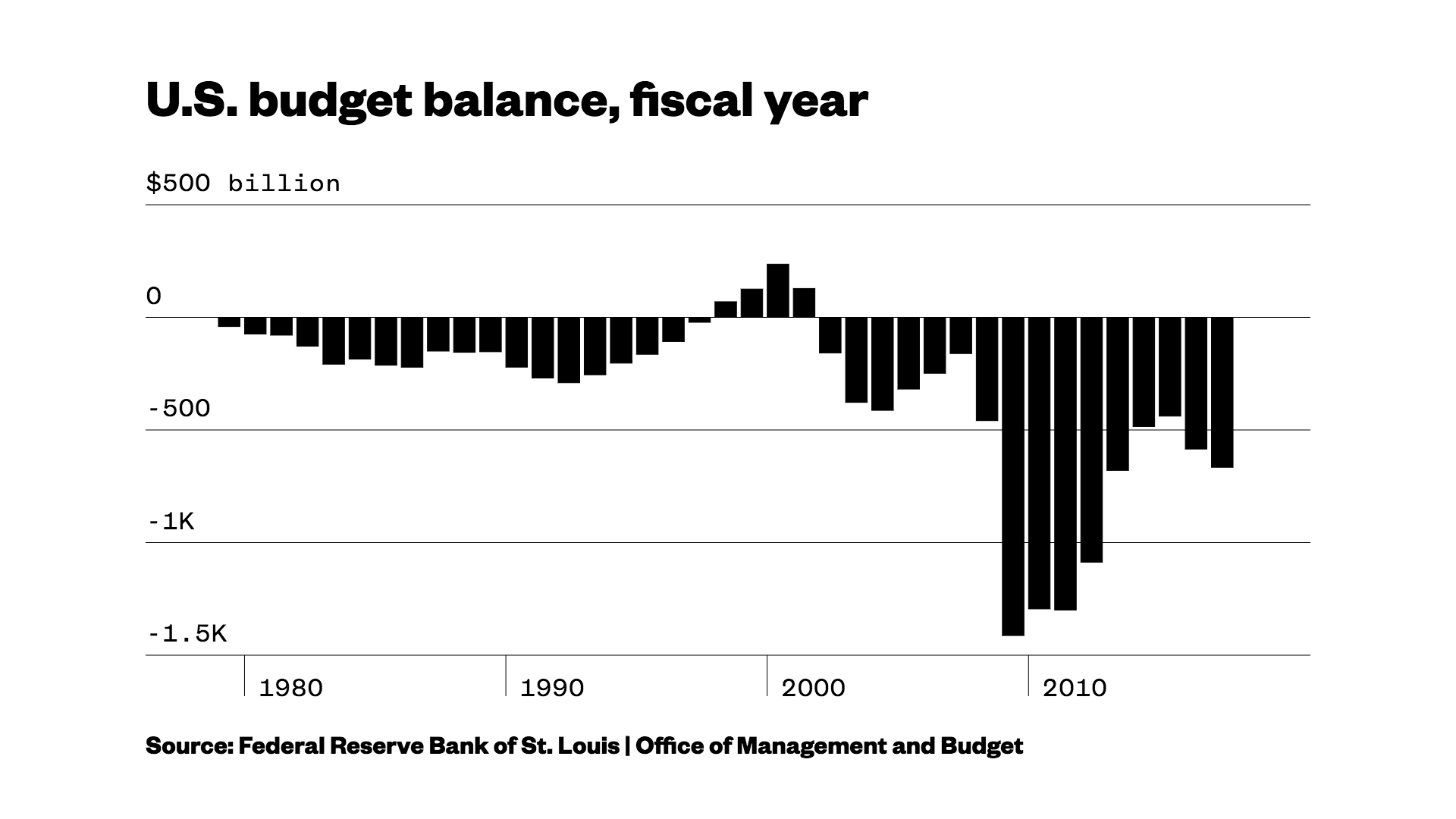

Now would be the time to start socking money away for a rainy day.The U.S. economy is in fairly good shape. Unemployment is low at 4.2 percent. Corporate profits are strong. Income levels are rising. Sure, there’s inequality, especially racial inequality. Wage growth isn’t stellar. And there are also signs of despair in some white working-class communities. But those are deep structural problems that won’t be fixed by the ups and downs of the U.S. economy. And from that perspective, the imperfect economy is doing perfectly fine.That means the economy needs less help from the government, particularly in the form of large deficits. But instead of shrinking deficits, we’re likely to get much larger ones over the next few years, courtesy of President Trump’s big shiny tax cuts.Deficits, the gap between the revenues the government collects and the spending it pays for, are tools governments use to boost economic growth. During recessions, deficits grow as the government spends more money on things like unemployment benefits and tax cuts designed to stimulate the economy.In theory, when things recover, the government pulls back on this spending and deficits start to shrink. This pause in spending gives the government the ability to save for the next recession, whenever that is.That’s pretty much where we should be right now. Except we’re not.Despite being eight years into an economic recovery, new data from the Treasury Department show that deficits continue to increase. Uncle Sam’s borrowing rose by $80 billion, to $666 billion, in the just-completed fiscal year. That was the biggest deficit in four years, and the second straight expansion of deficits, as spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid rose, as well as federal spending related hurricane relief. Much of that spending — with the exception of the storms — has long-been expected as the Baby Boom generation ages and requires more government assistance, particularly on health care.Rising costs associated with the baby boom generation are likely to last for decades, leaving the country with a series of stark financial choices.Cutting off America’s grandparents by doing away with Social Security and Medicare is politically impossible. You could keep tax levels where they are, and continue running large deficits. You could raise taxes and, if economic growth holds up, cut deficits, and possibly even get back into surplus territory. Or you could cut taxes and pray that economic growth surges and magically pays for everything.President Donald Trump’s current tax proposal is essentially the last option.Though Trump expects Congress to fill in details of the plan, the administration sketched out its main points. Trump wants to cut the tax rate on the highest-earning Americans down from 39.6 percent to 35 percent. He aims to axe corporate rates from 35 percent to 20 percent. And the plan calls for a new tax category for legal entities that pass-through their income and losses directly to owners — the structure of many U.S. small businesses — and tax the highest-earning of those companies at a 25 percent rate instead of 39.6 percent that they’d pay under the current law.These tax cuts are overwhelmingly aimed at America’s richest households. The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center says that over the next decade roughly 80 percent of the benefits of the tax cuts laid out in the administration’s “tax framework” will go to the top 1 percent of earners, who make more than $730,000 a year.Republicans in the White House claim that cutting taxes and regulations will raise economic growth, and the tax revenue generated by that growth, enough to help erase deficits. Few credible economists — including conservatives — agree. And the fact that Republican-controlled Senate just passed a budget resolution that provides for $1.5 trillion in additional deficits over the next decade seems to suggest that higher deficits are the likely outcome.

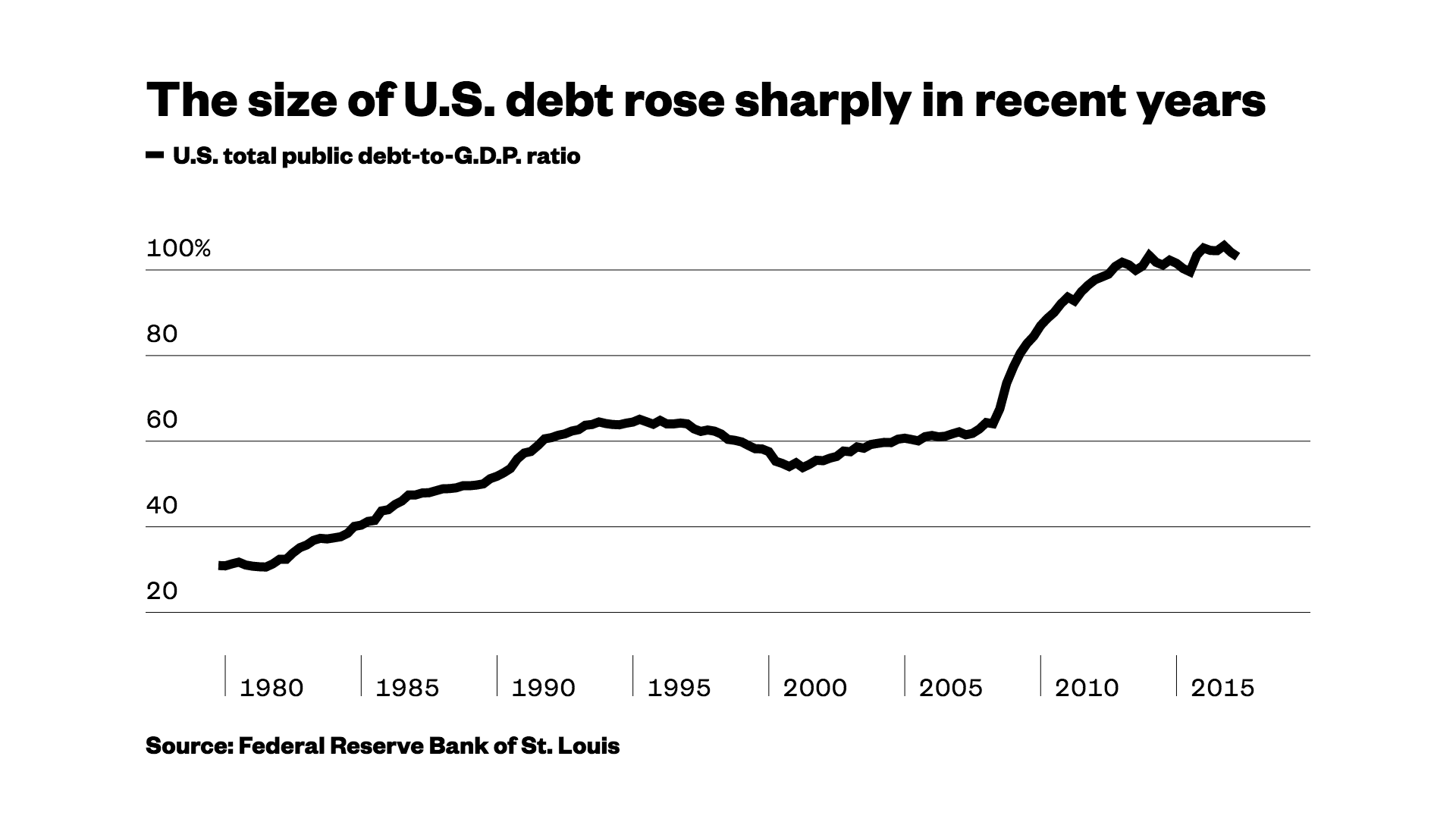

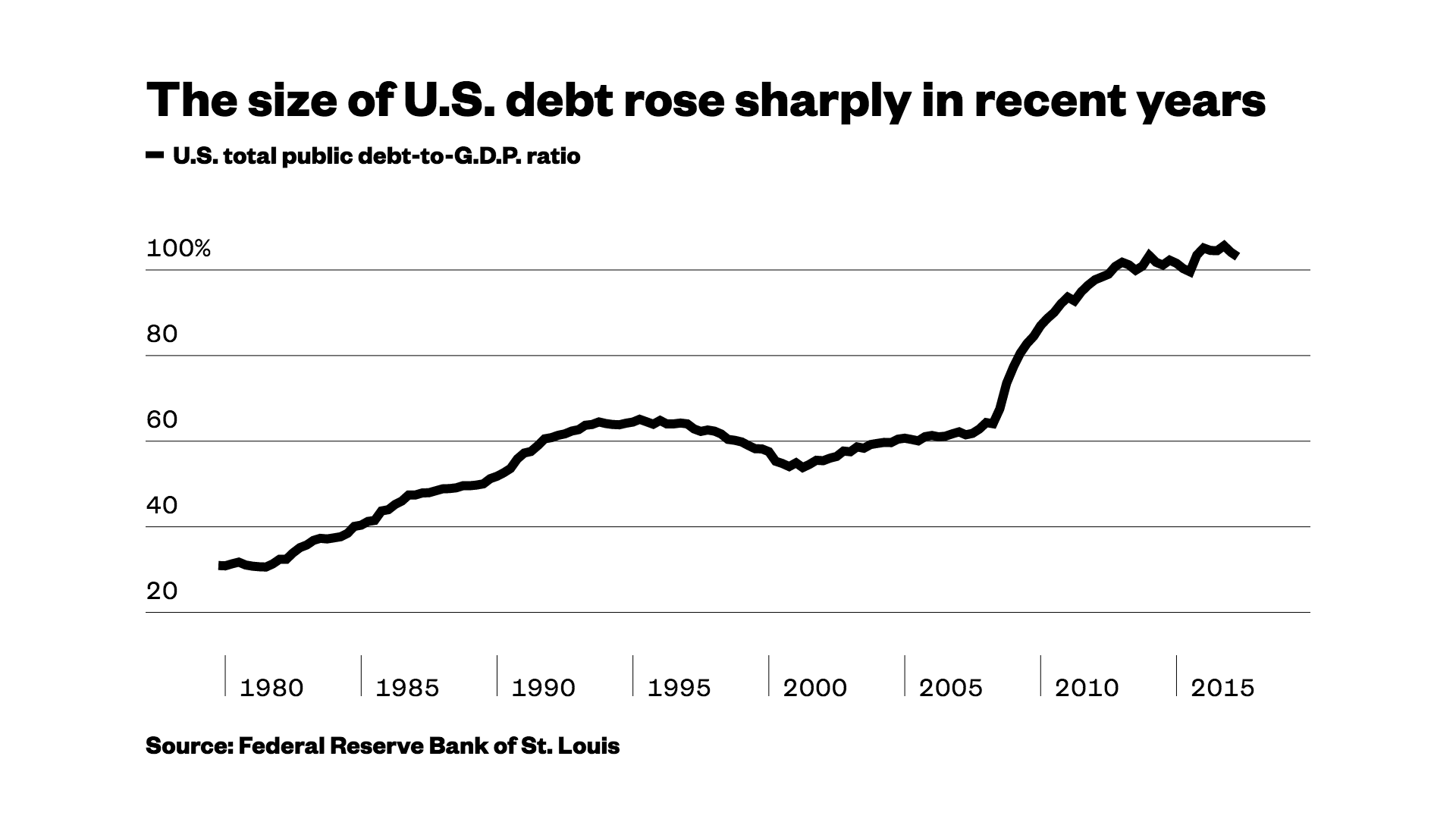

Much of that spending — with the exception of the storms — has long-been expected as the Baby Boom generation ages and requires more government assistance, particularly on health care.Rising costs associated with the baby boom generation are likely to last for decades, leaving the country with a series of stark financial choices.Cutting off America’s grandparents by doing away with Social Security and Medicare is politically impossible. You could keep tax levels where they are, and continue running large deficits. You could raise taxes and, if economic growth holds up, cut deficits, and possibly even get back into surplus territory. Or you could cut taxes and pray that economic growth surges and magically pays for everything.President Donald Trump’s current tax proposal is essentially the last option.Though Trump expects Congress to fill in details of the plan, the administration sketched out its main points. Trump wants to cut the tax rate on the highest-earning Americans down from 39.6 percent to 35 percent. He aims to axe corporate rates from 35 percent to 20 percent. And the plan calls for a new tax category for legal entities that pass-through their income and losses directly to owners — the structure of many U.S. small businesses — and tax the highest-earning of those companies at a 25 percent rate instead of 39.6 percent that they’d pay under the current law.These tax cuts are overwhelmingly aimed at America’s richest households. The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center says that over the next decade roughly 80 percent of the benefits of the tax cuts laid out in the administration’s “tax framework” will go to the top 1 percent of earners, who make more than $730,000 a year.Republicans in the White House claim that cutting taxes and regulations will raise economic growth, and the tax revenue generated by that growth, enough to help erase deficits. Few credible economists — including conservatives — agree. And the fact that Republican-controlled Senate just passed a budget resolution that provides for $1.5 trillion in additional deficits over the next decade seems to suggest that higher deficits are the likely outcome. Debt and deficits aren’t necessarily bad. Most advanced economies carry large amounts of debt. And there are times, such as during deep recessions or during wars, when running large deficits is appropriate. When the impact of the Great Recession slammed the country starting in 2008, both Republicans and Democrats wrote big checks to fight keep the economy from collapsing.That was the right thing to do. But as a result U.S. government debt — the stock of years of deficits — has surged to roughly 100 percent of G.D.P., high by U.S. standards.With the economy now largely recovered, it’s simply unwise to pile up a lot more debt unless you have a very good reason. And it’s hard to find one in Trump’s tax plan.

Debt and deficits aren’t necessarily bad. Most advanced economies carry large amounts of debt. And there are times, such as during deep recessions or during wars, when running large deficits is appropriate. When the impact of the Great Recession slammed the country starting in 2008, both Republicans and Democrats wrote big checks to fight keep the economy from collapsing.That was the right thing to do. But as a result U.S. government debt — the stock of years of deficits — has surged to roughly 100 percent of G.D.P., high by U.S. standards.With the economy now largely recovered, it’s simply unwise to pile up a lot more debt unless you have a very good reason. And it’s hard to find one in Trump’s tax plan.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement