While investigating a string of armed robberies between 2010 and 2012, the FBI arrested a man named Timothy Carpenter, largely because location data agents obtained from his cell phone put him within two miles of the crimes.They didn’t even need a warrant. And since no federal law requires one for cell phone location data, local law enforcement in most states can conduct the same type of searches.Right now, a murky web of federal and state statutes determine how easily cops can access data on Americans’ cell phones. While the Fourth Amendment requires a probable cause warrant to search personal property, the law hasn’t caught up with the ever-evolving nature of technology.At the end of November, however, Carpenter’s lawyers will argue in front of the Supreme Court that the FBI violated his Constitutional rights by searching his cell phone’s location data without a warrant. His case could change how law enforcement goes about finding and using information on Americans’ cell phones.Historically, the Fourth Amendment hasn’t protected searches of location data — basically, how a person or object gets from point A to point B — because of a legal theory called the third-party doctrine. When citizens release information to a third party like a cell phone service provider, the theory goes, they remove any “reasonable expectation of privacy” they might have had.Using that logic, cops in many states can piece together cell phone location data to construct a comprehensive portrait of how each of the 95 percent of Americans who own cell phones go about their lives, largely without legal limitations.While the Fourth Amendment doesn’t generally protect data voluntarily given over to a third party, the contents of that data or communication is a different story: It’s like how cops can take a package from the post office without a warrant, but officers can’t actually open the package to see what’s inside until they have one.But cell phone location data alone can paint a uniquely complete picture of who someone is. When police want to access to it, they run three basic types of searches. And the protections against each differ widely from state-to-state.For historical data searches, like what’s at question in Carpenter’s upcoming Supreme Court case, thirty-seven states don’t currently require a warrant — even though authorities can obtain days, weeks, or months of location records from specific phones. Eighteen of those states have specifically ruled that warrants aren’t required for historical location data, and the other nineteen lack an authority on the matter. Only eight states require warrants for all types of cell phone location data, and just one, Massachusetts, has specifically ruled that cops need a warrant to gather historical location data alone.A ruling in Carpenter could unify those conflicting authorities.READ: Supreme Court cases this term you should watch closely“Historical data is more of an unprecedented invasion because it represents a power of law enforcement that has never existed before,” said Nathan F. Wessler, an ACLU staff attorney who will argue on Carpenter’s behalf before the Supreme Court on Nov. 29. “It’s really a time machine that lets a police officer decide today that they want a comprehensive map of someone’s movement last year.”Cops generally go through phone companies to obtain historical cell location data. Service providers say, however, that even in states where laws don’t call for warrants, they still always require court orders to release this data, as mandated by the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. The act is the most recent comprehensive federal law controlling digital privacy, although it hasn’t fully caught up with technology since its passage in 1986. “This put us in an awkward position as Americans, since we’re being governed by a structure that is technologically insufficient for the digital age we live in,” said Alex Marthews, who chairs a Fourth Amendment advocacy group called Restore the Fourth.But filing for a court order is much simpler than getting a warrant, according to Marc Fliedner, a former New York state prosecutor who ran Brooklyn’s Major Narcotics Bureau from 2010 to 2014, just as cell location data was becoming more prevalent in criminal investigations. To get a court order, a police officer just needs to go before a judge and make an oral statement about how a particular type of search is relevant to an investigation. If the judge deems the officer’s sworn statement valid, she or he signs the order then and there.Warrants, on the other hand, require written testimony, lawyers, and more stringent standards for what justifications will be accepted before search privileges are granted. Warrants can typically be obtained in 24 to 48 hours, although exceptions do apply for emergency circumstances like terrorism, or when a violent suspect is loose on the streets.From January 2017 until June, Verizon, the largest wireless telecom company in the United States with just over 147 million subscribers, received 20,442 requests from law enforcement for historical location data, according to its biannual transparency report. Of these, three-quarters were obtained by court order, and the final quarter via warrants. The second largest service provider, AT&T, reported 36,133 requests for location data during the same time period. AT&T does not publicly state how many of these requests were granted using a court order or warrant and did not respond to multiple emailed requests for clarification.Police can also ask service providers, like Verizon or AT&T, for a “tower dump,” which gives officers access to all the location data from a certain tower (or towers) within a certain period. Officers then must comb through that data to identify potential numbers of interest.Like historical searches, tower dumps also generally don’t require warrants, although service providers still require court orders. For some service providers, these requests have increased in the last few years. For example, Verizon reported in its transparency report that police requested 14,630 tower dumps in 2016, up from just 3,200 in 2013. The report didn’t break down the numbers by warrant or court order, and Verizon didn’t respond to a request for clarification.Another type of search provides “real-time” information by pulling location data from phones as soon as they ping a cell tower. This method usually requires a warrant as a matter of practice, although only fourteen states explicitly require one. Federal judges, however, generally haven’t cited the Fourth Amendment as the reason; instead, they say there’s no federal law that explicitly allows this method of instantaneous tracking without a warrant.The laws around real-time searches get tricky. They’re generally considered to be a form of wiretaps, thus requiring a specific wiretap order, which is similar to a warrant but slightly more difficult to get.In practice, however, cops can ask service providers for real-time data — or they can just do it themselves — with cell-site simulators.

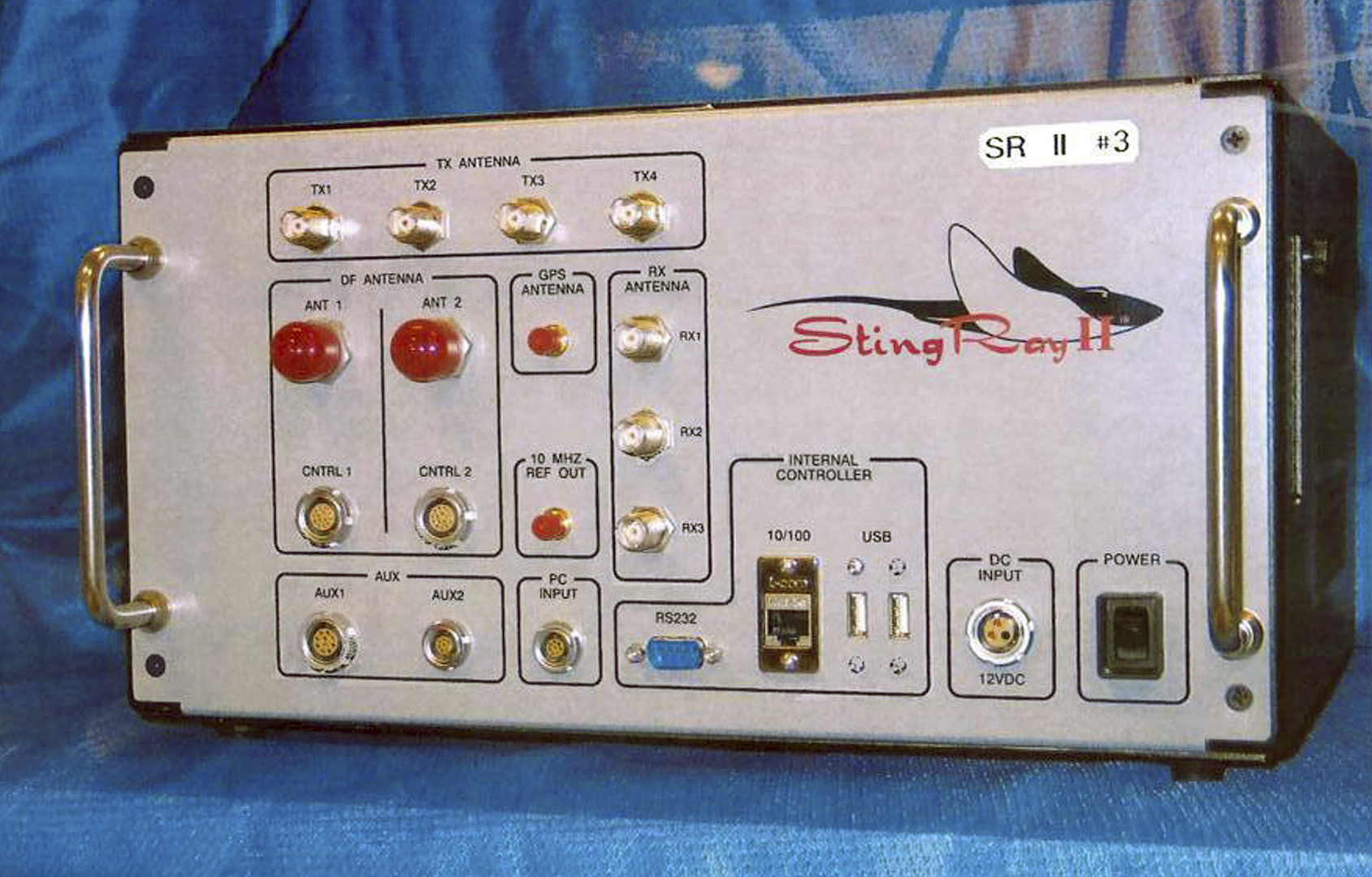

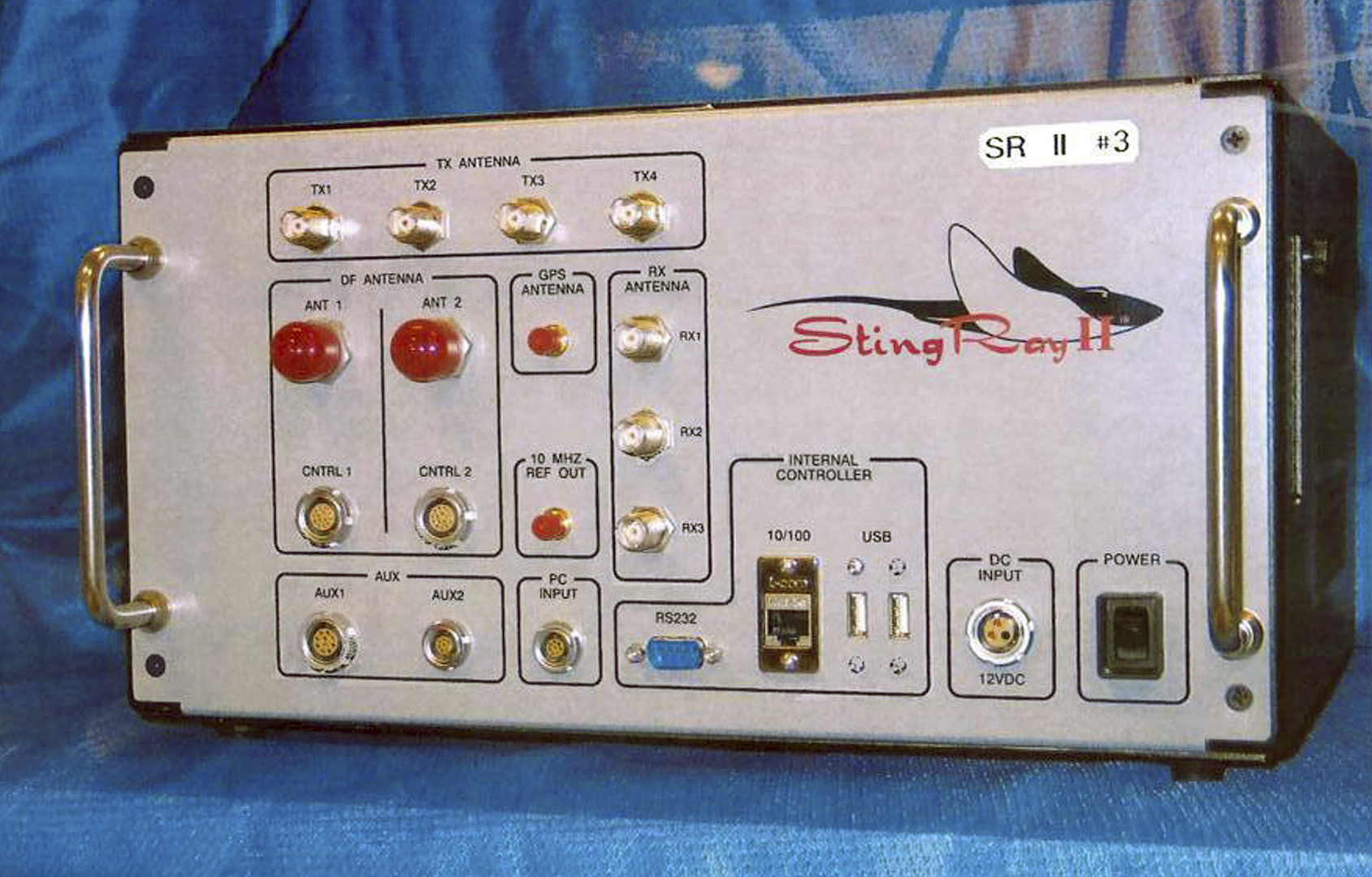

“This put us in an awkward position as Americans, since we’re being governed by a structure that is technologically insufficient for the digital age we live in,” said Alex Marthews, who chairs a Fourth Amendment advocacy group called Restore the Fourth.But filing for a court order is much simpler than getting a warrant, according to Marc Fliedner, a former New York state prosecutor who ran Brooklyn’s Major Narcotics Bureau from 2010 to 2014, just as cell location data was becoming more prevalent in criminal investigations. To get a court order, a police officer just needs to go before a judge and make an oral statement about how a particular type of search is relevant to an investigation. If the judge deems the officer’s sworn statement valid, she or he signs the order then and there.Warrants, on the other hand, require written testimony, lawyers, and more stringent standards for what justifications will be accepted before search privileges are granted. Warrants can typically be obtained in 24 to 48 hours, although exceptions do apply for emergency circumstances like terrorism, or when a violent suspect is loose on the streets.From January 2017 until June, Verizon, the largest wireless telecom company in the United States with just over 147 million subscribers, received 20,442 requests from law enforcement for historical location data, according to its biannual transparency report. Of these, three-quarters were obtained by court order, and the final quarter via warrants. The second largest service provider, AT&T, reported 36,133 requests for location data during the same time period. AT&T does not publicly state how many of these requests were granted using a court order or warrant and did not respond to multiple emailed requests for clarification.Police can also ask service providers, like Verizon or AT&T, for a “tower dump,” which gives officers access to all the location data from a certain tower (or towers) within a certain period. Officers then must comb through that data to identify potential numbers of interest.Like historical searches, tower dumps also generally don’t require warrants, although service providers still require court orders. For some service providers, these requests have increased in the last few years. For example, Verizon reported in its transparency report that police requested 14,630 tower dumps in 2016, up from just 3,200 in 2013. The report didn’t break down the numbers by warrant or court order, and Verizon didn’t respond to a request for clarification.Another type of search provides “real-time” information by pulling location data from phones as soon as they ping a cell tower. This method usually requires a warrant as a matter of practice, although only fourteen states explicitly require one. Federal judges, however, generally haven’t cited the Fourth Amendment as the reason; instead, they say there’s no federal law that explicitly allows this method of instantaneous tracking without a warrant.The laws around real-time searches get tricky. They’re generally considered to be a form of wiretaps, thus requiring a specific wiretap order, which is similar to a warrant but slightly more difficult to get.In practice, however, cops can ask service providers for real-time data — or they can just do it themselves — with cell-site simulators. These devices, known as Triggerfishes, Stingrays, or Hailstorms (as well as smaller ones called Jugulars or Wolfhounds), mimic the function of cell towers by tricking nearby cell phones into sending their locations and phone numbers to them. These machines can’t track historical cell phone location data, and instead pull information from phones as they ping cell towers, and the process sweeps up not only a suspect’s information but also bystanders’. Investigators, however, can still aggregate the data into a map of someone’s movements over time.“In the past, police could have gotten certain information without a warrant that could help them piece together where a suspect had been and [what they had] done, such as receipts. But they could never have constructed a multiple day map of movements over time,” the ACLU’s Wessler pointed out. “This totally upends expectations of privacy, it upsets the balance between people and government that the Fourth Amendment was intended to preserve.”READ: Did the NSA spy on El Chapo? His lawyer sure thinks so.The ACLU has counted 72 state and local law enforcement agencies in 24 states and D.C. that own Stingrays or similar trackers, but since these departments generally aren’t forthcoming about using these devices, there are likely many more.Federal agencies, like the DEA and FBI, have been required to obtain warrants for Stingray searches since 2015, but local law enforcement still sometimes operates in the shadows of investigation practices. Cops have used the third-party doctrine to justify using Stingrays and other similar machines without obtaining wiretap orders, which Wessler called “an even bigger stretch than in the Carpenter case.”The devices’ legitimacy, however, is increasingly being challenged in court, and judges have specifically called out the current interpretation of the third-party doctrine. Federal appellate courts in Maryland, and Washington, D.C. have ruled that police need a warrant to gather Stingray data. Still, a ruling in Maryland doesn’t affect police in Houston or Los Angeles — where courts haven’t haven’t ruled on whether these devices require warrants before they’re used.“Until either there’s action by Congress, or action by all the state legislatures, or action from the Supreme Court, there will still be a patchwork of rules and limitations on Stingrays,” Wessler said.Carpenter’s upcoming Supreme Court case could clarify these legal discrepancies and establish precedent that would vastly alter how law enforcement conducts routine searches of location data.

These devices, known as Triggerfishes, Stingrays, or Hailstorms (as well as smaller ones called Jugulars or Wolfhounds), mimic the function of cell towers by tricking nearby cell phones into sending their locations and phone numbers to them. These machines can’t track historical cell phone location data, and instead pull information from phones as they ping cell towers, and the process sweeps up not only a suspect’s information but also bystanders’. Investigators, however, can still aggregate the data into a map of someone’s movements over time.“In the past, police could have gotten certain information without a warrant that could help them piece together where a suspect had been and [what they had] done, such as receipts. But they could never have constructed a multiple day map of movements over time,” the ACLU’s Wessler pointed out. “This totally upends expectations of privacy, it upsets the balance between people and government that the Fourth Amendment was intended to preserve.”READ: Did the NSA spy on El Chapo? His lawyer sure thinks so.The ACLU has counted 72 state and local law enforcement agencies in 24 states and D.C. that own Stingrays or similar trackers, but since these departments generally aren’t forthcoming about using these devices, there are likely many more.Federal agencies, like the DEA and FBI, have been required to obtain warrants for Stingray searches since 2015, but local law enforcement still sometimes operates in the shadows of investigation practices. Cops have used the third-party doctrine to justify using Stingrays and other similar machines without obtaining wiretap orders, which Wessler called “an even bigger stretch than in the Carpenter case.”The devices’ legitimacy, however, is increasingly being challenged in court, and judges have specifically called out the current interpretation of the third-party doctrine. Federal appellate courts in Maryland, and Washington, D.C. have ruled that police need a warrant to gather Stingray data. Still, a ruling in Maryland doesn’t affect police in Houston or Los Angeles — where courts haven’t haven’t ruled on whether these devices require warrants before they’re used.“Until either there’s action by Congress, or action by all the state legislatures, or action from the Supreme Court, there will still be a patchwork of rules and limitations on Stingrays,” Wessler said.Carpenter’s upcoming Supreme Court case could clarify these legal discrepancies and establish precedent that would vastly alter how law enforcement conducts routine searches of location data.

Advertisement

How the law works now

For example, someone could drive across the border from Utah — where warrants are required for all types of cell location data — to Nevada — where the state Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that warrants are not required — and be subject to an entirely different legal framework regulating their private data.“Whether a state legislature steps in or not, there are basic constitutional protections that the Fourth Amendment provides,” said Andrew Crocker, staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a legal nonprofit dedicated to maintaining civil liberties in the digital world. Those protections, Crocker explained, shouldn’t change when people cross state lines.“Historical data is more of an unprecedented invasion because it represents a power of law enforcement that has never existed before.”

Advertisement

Historical searches

Advertisement

Advertisement

Tower dumps

Real-time searches

Advertisement

Advertisement